I wanted to take a minute to write about two stories related to claims for sites of Middle Pleistocene age in two different corners of the world. Unless you're grading papers in a lead-lined underground bunker, you heard about the claim for a 130,000-year-old archaeological site in California that was published in Nature yesterday. That's the first one. The second one involves an age estimate of 250,000 for the Homo naledi remains first described in September of 2015. The first claim is buzz-worthy because of its extreme earliness (a good 115,000 years prior to what most archaeologists accept as good evidence for human entry into the Americas). The second claim is surprising for its lateness. Let's do the second one first.

Homo naledi is Only 250,000 Years Old?

The announcement of Homo naledi and the results of the Rising Star Expedition made a huge splash in the fall of 2015 (I gave my take on it here). One of the main unresolved issues at the time of the initial announcement was that the remains were not dated. The lack of an age estimate made it difficult to frame the analysis in terms of evolutionary relationships with other hominins and the implications of the claims that Homo naledi was burying its dead. If the remains are very early (say, close to 2 million years old . . . ), the claims for organized mortuary behavior are spectacular. If they're very late, the mosaic of primitive and derived features becomes very curious.

Two days ago, the New Scientist ran a story titled "Homo naledi is Only 250,000 Years Old -- Here's Why that Matters." Here is a quote from that piece:

"Today, news broke that Berger’s team has finally found a way to date the fossils. In an interview published by National Geographic magazine, Berger revealed that the H. naledi fossils are between 300,000 and 200,000 years old.

“This is astonishingly young for a species that still displays primitive characteristics found in fossils about 2 million years old, such as the small brain size, curved fingers, and form of the shoulder, trunk and hip joint,” says Chris Stringer at the Natural History Museum in London."

A 250,000 year age would, indeed, be surprising. Previous age estimates have ranged widely, from 900,000 years old (based on dental and cranial metrics) to 2.5 to 2.8 million years old (based on overall anatomy). Age estimates based on the anatomical characteristics of the remains are problematic, obviously, as they rely on assumptions about the pattern, direction, and pace of evolutionary change that may not be correct. Hopefully the latest age estimates are independent of the anatomy (i.e., have a geological basis). This blog has some additional background.

A Middle Pleistocene Occupation of North America?

It's hard to know where to even start with this one. The claim is bold, the journal is prestigious, the popular press has been all over it, and the reaction from professionals has been swift and (as far as I can tell) overwhelmingly negative. The reactions I have seen among my colleagues and friends have been almost universally skeptical, ranging from amusement to mild outrage. I'll just summarize all that with gif I saw in an online discussion about the paper:

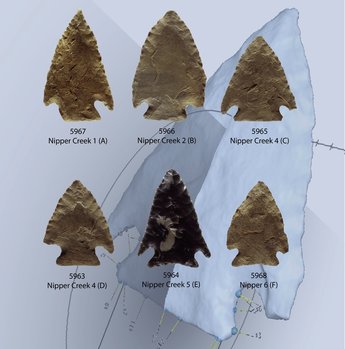

So how should we view claims like this one? For this claim to stand up, two main questions have to withstand scrutiny. First, is the material really that old? Second, is the material really evidence of human behavior?

If we accept the age of the remains, we're left with the second question about whether those remains show convincing evidence of human behavior. As you can see from the abstract, the claim for human activity has several components (modification of the bones, the presence and locations of stone cobbles interpreted as tools, etc.). The authors contention (p. 480) is that

The absence of cut marks would be perplexing, as we have direct evidence that hominins have been using using sharp stone tools to butcher animals since at least 3.4 million years ago. The 23,000-year-old human occupation of Bluefish Cave in the Yukon is supported by . . . cutmarks. We know that Neandertals and other Middle Pleistocene humans had sophisticated tool kits that were used to cut both animal and plant materials.

Is it possible that pre-Clovis occupations in this continent extend far back into time? Yes, I think it is. Does this paper convince me that humans messed around with a mastodon carcass in California at the end of the Middle Pleistocene? No, it does not.

One thing I can guarantee is that the "fringe" will be on the Cerutti Mastodon like a wet diaper: they've already got a laundry list of "Neanderthal" remains from the New World (some buried in Woodland-age earthen mounds!) and "pre-Flood" sites into which they'll weave this report into. Maybe Bigfoot will even be implicated. Maybe the mastodon was killed by Atlanteans.

Onward.

RSS Feed

RSS Feed