|

I don't know how many of you are still around, but I'm posting to let you know that I'm opening a new front on YouTube this Wednesday (February 2, 2021). Jim Vieira and I are teaming up to try an online program that we'll livestream on this channel. Here is my announcement of our first episode, which will focus on the Dragon Man skull and some other apparently "large" human remains from our evolutionary past: Here is the conversation where Jim and I discussed the basic ideas behind this endeavor: I don't have the skills or the software to stream anything other than a basic conversation at this point, but if people watch and/or we're having fun hopefully that will change. The program(s) will be available as videos after the livestreams.

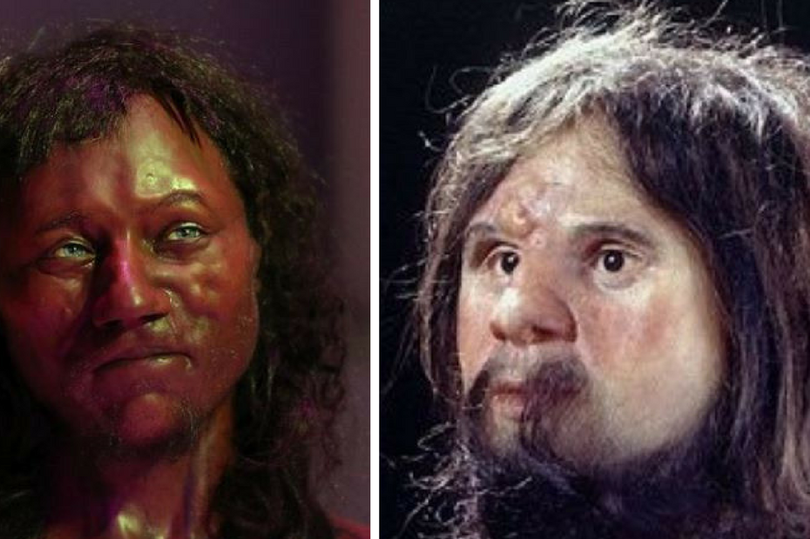

This week's announcement that a 10,000-year-old resident of Britain had dark skin and blue eyes has added another data point to our understanding of the complex and fascinating evolution of variability in human pigmentation. DNA analysis was used to give "Cheddar Man" a makeover: The portrait of a dark-complected Cheddar Man has upset many racist modern Britons, who were comfortable with a lighter-skinned ancestor. White supremacists are attributing the change in Cheddar Man's skin tone to political correctness, cultural Marxism, and a hoax perpetrated by the UN and Jewish scientists.

These blanket rejections of the science responsible for Cheddar Man's new look come from the same crowd that, just two weeks ago, hailed the announcement of a 200,000-year-old "modern human" fossil from Israel as a significant blow to the Out of Africa theory. Oh you fickle racists. In reality, the claim that a European from the Early Holocene probably had dark skin and blue eyes is unsurprising in light of other recent work suggesting that lightened skin pigmentation emerged relatively recently in European populations. These conclusions are not the result of agenda-driven guesswork, but of direct analysis of DNA. Have a look at the paper from the La Brana specimen for an example. Data on the recent emergence of "whiteness" among European populations undercuts the white supremacist notion that light skin tone is ancient, "special," and somehow linked to inherent biological/cultural superiority. It's a very short step from the modern mythologies of white supremacy into numerous threads of pseudo-archaeology, many of which depend on the existence of ancient "white gods," "white giants," "white Atlanteans," etc. The real stories of human variability are much more interesting than the fantasy ones. I recommend embracing evidence.

It's the end-of-semester crunch for many of us in the academic world. My Facebook feed is filled with posts by people who been grading for too long and finding too many cases of student plagiarism. The end of my road was easy this semester, as I taught a very pleasant field school populated by a good group of students. Having taught a 4/4 one year, I feel for all of you still slogging away.

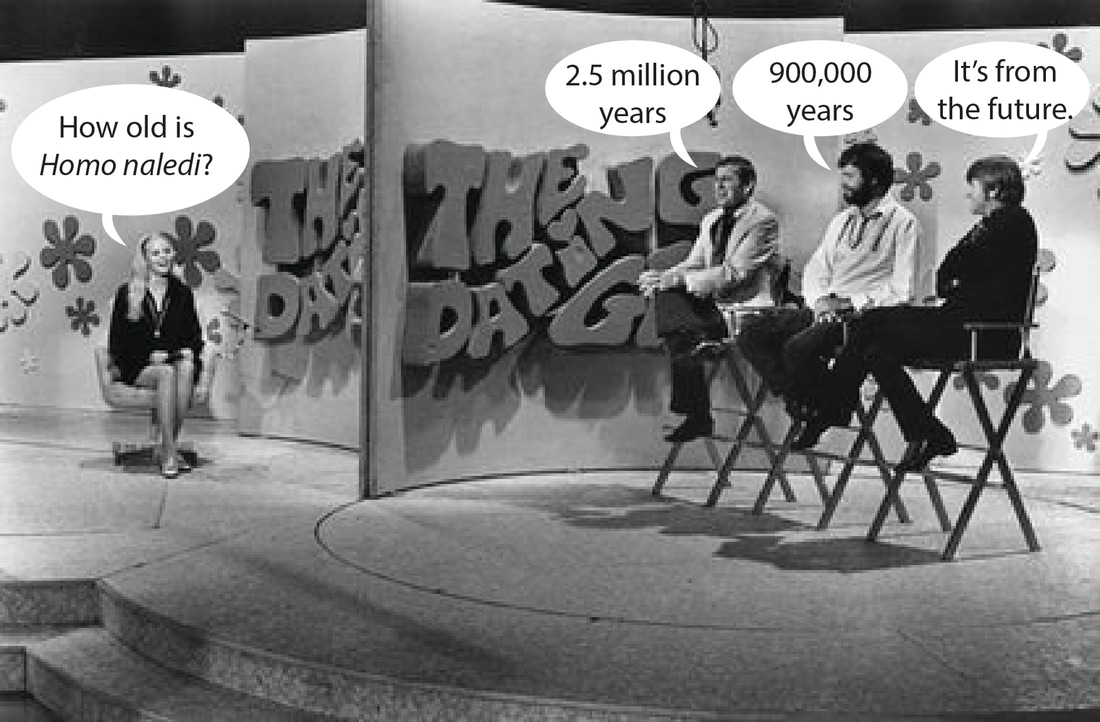

I wanted to take a minute to write about two stories related to claims for sites of Middle Pleistocene age in two different corners of the world. Unless you're grading papers in a lead-lined underground bunker, you heard about the claim for a 130,000-year-old archaeological site in California that was published in Nature yesterday. That's the first one. The second one involves an age estimate of 250,000 for the Homo naledi remains first described in September of 2015. The first claim is buzz-worthy because of its extreme earliness (a good 115,000 years prior to what most archaeologists accept as good evidence for human entry into the Americas). The second claim is surprising for its lateness. Let's do the second one first. Homo naledi is Only 250,000 Years Old? The announcement of Homo naledi and the results of the Rising Star Expedition made a huge splash in the fall of 2015 (I gave my take on it here). One of the main unresolved issues at the time of the initial announcement was that the remains were not dated. The lack of an age estimate made it difficult to frame the analysis in terms of evolutionary relationships with other hominins and the implications of the claims that Homo naledi was burying its dead. If the remains are very early (say, close to 2 million years old . . . ), the claims for organized mortuary behavior are spectacular. If they're very late, the mosaic of primitive and derived features becomes very curious. Two days ago, the New Scientist ran a story titled "Homo naledi is Only 250,000 Years Old -- Here's Why that Matters." Here is a quote from that piece: "Today, news broke that Berger’s team has finally found a way to date the fossils. In an interview published by National Geographic magazine, Berger revealed that the H. naledi fossils are between 300,000 and 200,000 years old. “This is astonishingly young for a species that still displays primitive characteristics found in fossils about 2 million years old, such as the small brain size, curved fingers, and form of the shoulder, trunk and hip joint,” says Chris Stringer at the Natural History Museum in London."

If you click on the link to the interview in National Geographic, you'll find that it leads to a photograph of a magazine page posted on Twitter by Colin Wren. I'm unable to access the original piece in National Geographic. I'm not quite sure what is going on, but presumably a formal publication explaining the age estimate is in the works and will be out soon.

A 250,000 year age would, indeed, be surprising. Previous age estimates have ranged widely, from 900,000 years old (based on dental and cranial metrics) to 2.5 to 2.8 million years old (based on overall anatomy). Age estimates based on the anatomical characteristics of the remains are problematic, obviously, as they rely on assumptions about the pattern, direction, and pace of evolutionary change that may not be correct. Hopefully the latest age estimates are independent of the anatomy (i.e., have a geological basis). This blog has some additional background.

And now on to the second one, which concerns . . .

A Middle Pleistocene Occupation of North America? It's hard to know where to even start with this one. The claim is bold, the journal is prestigious, the popular press has been all over it, and the reaction from professionals has been swift and (as far as I can tell) overwhelmingly negative. The reactions I have seen among my colleagues and friends have been almost universally skeptical, ranging from amusement to mild outrage. I'll just summarize all that with gif I saw in an online discussion about the paper:

The claim centers around an assemblage of stones and mastodon bones that the authors interpret as unequivocal evidence of human activity in California at the Middle/Late Pleistocene transition (ca. 130,000 years ago). Here is the first part of the abstract of the Nature paper by Steven Holen and colleagues:

"The earliest dispersal of humans into North America is a contentious subject, and proposed early sites are required to meet the following criteria for acceptance: (1) archaeological evidence is found in a clearly defined and undisturbed geologic context; (2) age is determined by reliable radiometric dating; (3) multiple lines of evidence from interdisciplinary studies provide consistent results; and (4) unquestionable artefacts are found in primary context. Here we describe the Cerutti Mastodon (CM) site, an archaeological site from the early late Pleistocene epoch, where in situ hammerstones and stone anvils occur in spatio-temporal association with fragmentary remains of a single mastodon (Mammut americanum). The CM site contains spiral-fractured bone and molar fragments, indicating that breakage occured while fresh. Several of these fragments also preserve evidence of percussion. The occurrence and distribution of bone, molar and stone refits suggest that breakage occurred at the site of burial. Five large cobbles (hammerstones and anvils) in the CM bone bed display use-wear and impact marks, and are hydraulically anomalous relative to the low-energy context of the enclosing sandy silt stratum. 230Th/U radiometric analysis of multiple bone specimens using diffusion–adsorption–decay dating models indicates a burial date of 130.7 ± 9.4 thousand years ago. These findings confirm the presence of an unidentified species of Homo at the CM site during the last interglacial period (MIS 5e; early late Pleistocene), indicating that humans with manual dexterity and the experiential knowledge to use hammerstones and anvils processed mastodon limb bones for marrow extraction and/or raw material for tool production."

The 130,000 year-old date is way, way, way out there in terms of the accepted timeline for humans in the Americas. Does that mean the conclusions of the study are wrong? Of course not. And, honestly, I don't even necessarily subscribe to the often-invoked axiom that "extraordinary claims require extraordinary evidence." I think ordinary, sound evidence works just fine most of the time when you're operating within a scientific framework. Small facts can kill mighty theories if you phrase your questions in the right way.

So how should we view claims like this one? For this claim to stand up, two main questions have to withstand scrutiny. First, is the material really that old? Second, is the material really evidence of human behavior? If we accept the age of the remains, we're left with the second question about whether those remains show convincing evidence of human behavior. As you can see from the abstract, the claim for human activity has several components (modification of the bones, the presence and locations of stone cobbles interpreted as tools, etc.). The authors contention (p. 480) is that

"Multiple bone and molar fragments, which show evidence of percussion, together with the presence of an impact notch, and attached and detached cone flakes support the hypothesis that human-induced hammerstone percussion was responsible for the observed breakage. Alternative hypotheses (carnivoran modification, trampling, weathering and fluvial processes) do not adequately explain the observed evidence (Supplementary Information 4). No Pleistocene carnivoran was capable of breaking fresh proboscidean femora at mid-shaft or producing the wide impact notch. The presence of attached and detached cone flakes is indicative of hammerstone percussion, not carnivoran gnawing (Supplementary Information 4). There is no other type of carnivoran bone modification at the CM site, and nor is there bone modification from trampling."

My impression is that most archaeologists are, like me, are skeptical that all other possible explanations for the stone and bone assemblage can be confidently rejected. I'm no expert on paleontology and taphonomy, but as I thought through the suggested scenario, I wondered how all the meat came off the bones before before the purported humans smashed them open with rocks. The authors state that there's no carnivore damage, and unless I missed it I didn't see any discussion of cutmarks left by butchering the carcass with stone tools. So where did the meat go? If it wasn't removed by animals (no carnivore marks) and wasn't removed by humans (no cutmarks) did it just rot away? If so, would the bones have still been "green" for humans to break them open?

The absence of cut marks would be perplexing, as we have direct evidence that hominins have been using using sharp stone tools to butcher animals since at least 3.4 million years ago. The 23,000-year-old human occupation of Bluefish Cave in the Yukon is supported by . . . cutmarks. We know that Neandertals and other Middle Pleistocene humans had sophisticated tool kits that were used to cut both animal and plant materials. Is it possible that pre-Clovis occupations in this continent extend far back into time? Yes, I think it is. Does this paper convince me that humans messed around with a mastodon carcass in California at the end of the Middle Pleistocene? No, it does not.

Some of my friends seem angry that the paper was published. I have mixed feelings. I'm not at all convinced by what I've read so far, but I think claims like this serve a useful purpose whether or not they turn out to be correct. I can understand the concerns I've heard voiced about unfairness in the standards of evidence and argument that are acceptable at various levels of publication, but I also think there should always be room for making bold claims about the past as long as those claims have some basis in material evidence that can be independently evaluated. It will be interesting to see how the buzz over this paper plays out. Will other professionals carefully examine the remains and offer up their opinions? Will the claim be quickly dismissed and forgotten about?

One thing I can guarantee is that the "fringe" will be on the Cerutti Mastodon like a wet diaper: they've already got a laundry list of "Neanderthal" remains from the New World (some buried in Woodland-age earthen mounds!) and "pre-Flood" sites into which they'll weave this report into. Maybe Bigfoot will even be implicated. Maybe the mastodon was killed by Atlanteans. Onward.  Next up in my Forbidden Archaeology class is a critical reading of the 2015 book Species with Amnesia by Robert Sepehr. I chose this book because it checked the boxes for many of the issues that I'd like to address in our section on "ice age civilization" and I could find no existing, detailed, online appraisal of its claims. I'm quickly working my way through the book this weekend, prepping for our in-class discussions and assembling a list of topics for the students' next round of blog posts. My plan is to do a sort of distributed "group" critique of the book, assigning a small section or particular claim to each of the twenty students. While I'm familiar with many of the things discussed in the book, it is jam packed with assertions about "evidence" that I've never come across before. It will be fun to turn the students loose on a set of those claims and see what they come up with. Another thing that I've discovered during my quick reading is . . . wait for it . . . plagiarism! This probably will not come as a shock to those of you familiar with these kinds of works, as plagiarism is endemic in the "fringe" world. I don't yet have a sense of how much of the content of the book is thinly-modified cut-and-paste, I just know that I've stumbled onto several examples without even really trying. Here's a passage from Species with Amnesia about the Peruvian "Lady of the Mask" mummy (page 102): "Piercing blue eyes undimmed by the passing of 1,300 years, this is the "Lady of the Mask" a mummy with striking blue eyes, whose discovery could reveal the secrets of a lost culture at the Huaca Pucllana Pyramid located in Lima, Peru." And here are the first two paragraphs of a 2008 article in the Daily Mail: "Piercing blue eyes undimmed by the passing of 1,300 years, this is the Lady of the Mask – a mummy whose discovery could reveal the secrets of a lost culture. She was found by archaeologists excavating a pyramid in Peru’s capital city Lima, alongside two other adult mummies and the sacrificial remains of a child." (Note to students: adding quotation marks around a phrase ("Lady of the Mask") and deleting a hyphen does not transform someone else's work into your own work. I don't see the Daily Mail article in the bibliography, and there are no citations in the paragraph. That's pretty clear and simple. I found a more tangled case in one of Sepehr's discussions of Cro-Magnon. He seems to have paraphrased and sometimes borrowed directly either from a piece by Carson Reed on this website (about Cro-Magnon, Atlantis, and the teachings of Madame Blavatsky) or from R. Cedric Leonard (also used by Reed). Here is a passage from Species with Amnesia (page 49): "Many Cro-Magnon villages consisted of houses, but we don't know what they were made of. All we have are the remains of hearths and post hole patterns." Here is a sentence from Reed's piece: "These cave men also had houses! We do not know what exactly they were made of but we do have the post holes." Here is another passage from Species with Amnesia (page 45): "Professor of anthropology at Rutgers University, Dr. John E. Pfeiffer, observes that the Aurignacian was quite distinct and that it arrived from some area outside of Western Europe; with an already "established way of life."" And from Reed's piece: "Dr. John E. Pfeiffer, professor of anthropology at Rutgers University observes: "The Aurignacian is quite distinct from the Parigordian" [ a separate older European style ]; they arrive "from some area outside of Western Europe"; with an already "established way of life."" Reed cites R. Cedric Leonard at the end of this section and provides a URL. Sepehr cites Leonard's (2011) book after his sentence about Pfeiffer. On Leonard's webpage we find this sentence: "Dr. John E. Pfeiffer, professor of anthropology at Rutgers University observes: "The Aurignacian is quite distinct from the Perigordian"; they arrive "from some area outside of Western Europe"; with an already "established way of life."" So it's possible that Sepehr plagiarized Reed, or perhaps plagiarized Leonard directly. I suppose it doesn't really matter. As I skimmed through Leonard's webpage, I recognized more sentences from Species with Amnesia. Compare these two passages: "In an article entitled "Why don't We Call Them Cro-Magnon Anymore?", K. Krist Hirst suggests that the physical dimensions of Cro-Magnon specimens are not sufficiently different from modern humans to warrant a separate designation. Leonard raises the concern that this would make it all too convenient to eliminate the embarrassing origin problem. And what about the even more important cultural differences (totally differing tool kits, settlement patterns, art impulse, etc.)? (38) Are we to simply "bland out" all these diversities under one designation? This doesn't strike me as a scientific practice." That's from Species with Amnesia (page 48). This is from Leonard's webpage: "In an article entitled "Why don't We Call Them Cro-Magnon Anymore?" the author K. Krist Hirst suggests that the physical dimensions of Cro-Magnon specimens are not sufficiently different from modern humans to warrant a separate designation. My concern, of course, is that this would make it all too convenient to eliminate the embarrassing origin problem. And what about the even more important culture differences (totally differing tool kits, settlement patterns, art impulse, etc.)? Are we to simply "bland out" all these diversities under one designation? This doesn't strike me as scientific anthropological practice." The (38) in Sepehr's passage is a citation to Leonard's book, so he is acknowledging him in some way. But any real scholar (and, indeed, any reasonably honest high school student) will tell you that dropping a citation in the middle of a paragraph copied almost word-for-word but not quoted is Plagiarism 101. A person reading Sepehr's passage is left with the impression that the idea of "important cultural differences" came from Leonard but all the the other ideas and words are Sepehr's. Obviously that's not the case. Hopefully there are some original ideas and some original writing in Species with Amnesia. I'd rather spend my time addressing those then stumbling over sloppy plagiarism. Update (10/8/2016): This is turning into a bummer. A passage from this webpage ("Atlantis the Myth" by Alan G. Hefner) appears word for word in Species with Amnesia (pages 107-108): "According to ancient Egyptian temple records the Athenians fought an aggressive war against the rulers of Atlantis some nine thousand years earlier and won.These ancient and powerful kings or rulers of Atlantis had formed a confederation by which they controlled Atlantis and other islands as well. They began a war from their homeland in the Atlantic Ocean and sent fighting troops to Europe and Asia. Against this attack the men of Athens formed a coalition from all over Greece to halt it. When this coalition met difficulties their allies deserted them and the Athenians fought on alone to defeat the Atlantian rulers. They stopped an invasion of their own country as well as freeing Egypt and eventually every country under the control of the rulers of Atlantis." The section right after that (pages 108-109) is apparently cribbed directly from this 2013 blog post, changing a few words. Then the section on Iran (page 109) has sections apparently from this webpage. Update (10/8/2016):

The section on the Berbers (pages 86-87) also apparently contains plagiarized material. From Species with Amnesia: "The Berbers are considered the aboriginals of the area and their origins beyond that are not officially known. Many theories have been advanced relating them to the Canaanites, the Phoenicians, the Celts, and the Caucasians from Anatolia. In classical times the Berbers formed such states as Mauritania and Numidia." Here is a section from the same Carson Reed piece discussed earlier: "From a useful traditional source: Despite a history of conquests, the Berbers retained a remarkably homogeneous culture, which, on the evidence of Egyptian tomb paintings, derives from earlier than 2400 B.C. The alphabet of the only partly deciphered ancient Libyan inscriptions is close to the script still used by the Tuareg. The origins of the Berbers are uncertain, although many theories have been advanced relating them to the Canaanites, the Phoenicians, the Celts, the Basques, and the Caucasians. In classical times the Berbers formed such states as Mauritania and Numidia. (http://www.answers.com/topic/berber-people)" So Sepehr apparently just copied his analysis of the Berbers from answers.com. Great. Continuing on, part of his discussion of the Guanaches of the Canary Islands matches text on this DNA ancestry site. Here is a passage from Species with Amnesia (page 88): "Isolated in their islands, the Guanches preserved their pristine Cro-Magnon genetic traits in a more or less pure fashion until the arrival of the Spanish." And from Family Tree DNA: "Isolated in their islands, the Guanches were prevented, until the advent of the Spanish, from sexually mingling with other races. So, they preserved their pristine Cro-Magnon genetic traits in a more or less pure fashion until that date." Back in May I wrote this post about famous racist anthropologist Ernst Haeckel's ideas about human evolution and the lost continent of Lemuria. In the late 1800's, Haeckel proposed that some kind of "speechless men or ape-like men" was the common ancestor of the various human populations that he thought were actually different species. Haeckel used the term Pithecanthropi (literally "ape men") to refer to his proto-humans. I found it interesting that Haeckel was using the term Pithecanthropi years before it was used to name the "Java Man" fossils found by Eugene Dubois in Indonesia in 1891. As best I can tell, Haeckel coined "Pithecanthropi" to describe his hypothetical, speechless proto-human "missing link" between apes and humans (the earliest use of the term I can find is in the 1876 edition of History of Creation). Haeckel invented Pithecanthropi to describe something that he thought should have existed according to his model of human evolution, rather than something that could be shown to have actually existed based on fossil evidence. Pithecanthropus was a pre-construction rather than a re-construction.  Gabriel Max's (1894) illustration of Pithecanthropus. Gabriel Max's (1894) illustration of Pithecanthropus. Haeckel's manufactured genus was so important to his ideas about human evolution that artist Gabriel Max gave Haeckel a drawing of a family of Pithecanthropus for his 60th birthday in 1894. The picture displays the human-like differentiated hands and feet that Haeckel presumed would have been present. (An aside: look closely at the female's right foot -- it looks to me like she has a divergent big toe. It's interesting that available fossil evidence [such as Little Foot] demonstrate that Australopithecines retained a somewhat opposable big toe like non-human apes. A grasping toe is also present in the the 4.4 million-year-old skeleton of Ardipithecus ramidus, which may or may not be a human ancestor. There is no evidence that I know of which suggests that Homo erectus had a foot significantly different from modern humans). So why did Eugene Dubois name his fossils Pithecanthropus erectus? Was the choice of name an endorsement of Haeckel's ideas? Yes, apparently. Dubois wasn't a student of Haeckel's, but was apparently significantly influenced by Haeckel's ideas both in terms of the notion that there should be a "missing link" between apes and humans and fossil evidence for that creature could likely be found in tropical Asia. Dubois' decision to name the fossils he found in Indonesia Pithecanthropus is not a coincidence but a direct reflection of his appreciation for Haeckel's ideas about human evolution. It seems that Dubois' decision to look for the "missing link" in southeast Asia wasn't just some random gamble based on an original idea he had that humans were descended from orangutans: it was inspired by Haeckel's writings. The biography of Dubois on Talk Origins doesn't mention a connection between Dubois' ideas and those of Haeckel. The New World Encyclopedia entry about Dubois also doesn't mention Haeckel (but Dubois' Wikipedia entry does). Pat Shipman's 2002 biography of Dubois (The Man Who Found the Missing Link), which I have not yet read, also discusses the connection between Haeckel and Dubois. I think we could do a better job of confronting the history of racism in our discipline. While our current ideas about human evolution may ultimately be unaffected by whatever was in Dubois' head when he found the first fossils of what we now classify as Homo erectus in Indonesia, it isn't appropriate to try to scrub the "discovery" narrative clean of its historical and cultural context. I'm not saying that's what's happening here, but it's interesting that so many online sources of information about Dubois don't mention what looks like a fairly clear relationship between his career path and Haeckel's ideas. Current and Not-So-Current Events: Excavation, Moving, and Other Early Summer Odds and Ends5/27/2016

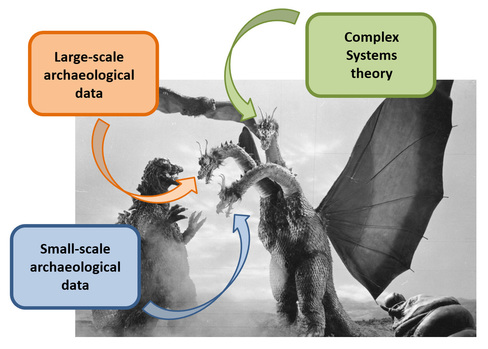

My new home. My new home. It's been two weeks since my last blog post. I've spent much of that two weeks away from my computer, which has been a nice change. Since the semester ended, I've been working in the field, doing stuff around the house and with my family, and prepping my office for a move. Today I'm relocating from the main SCIAA building to a larger, nicer office suite right in the heart of campus. I'll have plenty of room to ramp up my research, process and analyze artifacts, store collections I'm working on, and (hopefully) start getting some student work going. It's really an amazing thing to have the space -- it's larger and nicer than many fully functional archaeology labs where I've worked in the past. A 6000-Year-Old Moment Frozen in Time? Archaeological sites are places that contain material traces of human behavior. While the human behaviors that create archaeological sites are ultimately those of individuals, we usually can't resolve what we're looking at to that level. Traces of individual behaviors overprint one another and blend into a collective pattern. The granularity of individual behavior is usually lost. Usually, but not always. I spent portions of the last couple of works doing some preliminary excavation work at a site I first wrote about last October. Skipping over the details for now, documentation of an exposed profile measuring about 2.2 meters deep and 10 meters long showed the presence of cultural materials and intact features at several different depths. The portion of the deposits I am most interested in is what appears to be a buried zone of dark sediment, fire-cracked rock, and quartz knapping debris about 1.9 meters below the present ground surface. Based on the general pattern here in the Carolina Piedmont and a couple of projectile points recovered from the slump at the base of the profile, I'm guessing that buried cultural zone dates to the Middle Archaic period (i.e., about 8000-5000 years ago).  A buried assemblage of quartz chipping debris, probably created by a single individual during a single knapping episode. A buried assemblage of quartz chipping debris, probably created by a single individual during a single knapping episode. I did quite a bit of thinking to come up with my plan to both stabilize/preserve the exposed profile and learn something about the deposits. After I cleaned and documented the machine-cut profile as it existed, I established a coordinate system and began systematically excavating a pair of 1x1 m units that cut into the sloping face of the profile above the deposit of knapping debris visible in the wall. Excavating those partial units allowed me to simultaneously plumb the wall and expose the deposit of knapping debris in plan view. While there is no way to know for sure yet, I think I exposed most of the deposit, which seemed to be a scatter of debris with a concentration of large fragments in a space less than 60 cm across (an unknown amount of the deposit was removed during the original machine excavation, and I recovered numerous pieces of quartz debris from the slump beneath the deposit). My best guess is that pile of debris probably marks where a single individual sat for a few minutes and worked on creating tools from several locally-available lumps of quartz. I piece-plotted hundreds of artifacts as I excavated the deposit, so I'll be able to understand more about how it was created when I piece everything back together.  I did what I came to do. I did what I came to do. The site I've been working on would be a great one for a field school. It is close to Columbia and has all kinds of interesting archaeology -- great potential for both research and teaching. This May I was out there by myself. It took just about every move of fieldwork jiu jitsu I know (and several that I had to invent on the spot) to do what I did to stabilize the site and get it prepped for a more concerted effort, but I think it's in good shape now. Once I get moved into my new lab space I'll be able to start processing the artifacts and doing a preliminary analysis. I'll keep you posted. The Anthropology of Prehistoric Hunter-Gatherers in the Eastern Woodlands? Earlier in the month, I had the privilege of visiting the archaeological field schools being conducted at Topper. I wrote a little bit about the claim for a very early human presence at Topper here. The excavations associated with that claim aren't currently active. Field schools focused on Late Pleistocene/Early Holocene (Mississippi State University and the University of West Georgia) and Woodland/Mississippian (University of Tennessee) components at Topper and nearby sites have been running since early May. Seeing three concurrent field schools being run with the cooperation of personnel from four universities (and many volunteers) is remarkable.  On the day of my visit, I gave a talk titled "The Anthropology of Prehistoric Hunter-Gatherers in the Eastern Woodlands?" I argued that not only is it possible to do the anthropology of prehistoric peoples, but it should be a fundamental goal. Skipping over the details for now, I argued (as I have elsewhere) that complex systems science provides a set of tools for systematically trying to understand how history, process, and environment combine to produce the long-term, large-scale trajectories of prehistoric change that we can observe and analyze using archaeological data. I talked about each of the components of my three-headed monster research agenda. And I got to eat various venison products prepared under the direction of my SCIAA colleague Al Goodyear. And I got to see alligators swimming in the Savannah River. As a native Midwesterner . . . I anticipate that working near alligators will remain outside my comfort zone for some time to come. When Did Humans First Move Out of Africa? Archaeologists love finding the earliest of anything and people love reading about it. While we often want to know how/when new things appear, identifying the "earliest of X" often gets play in the popular press that is disproportionate to its relevance to a substantive archaeological/anthropological question. And you can never really be sure, of course, that you've nailed down the earliest of anything: someone else could always find something earlier, falsifying whatever model was constructed to account for the existing information and moving the goal posts. Exactly a year ago, I wrote about the reported discovery of 3.3 million-year-old stone tools from a site in Kenya. Those tools are significantly earlier than the previous "earliest" Oldowan tools. I think they're really interesting but not particularly surprising: several other lines of evidence (cut marks on bone, tool-use among chimpanzees, and hominin hand anatomy) already suggested that our ancestors were using tools well before the earliest Oldowan technologies appeared. I anticipate that we still haven't seen the "earliest" stone tool use. A recent report from India argues that our ideas about the "earliest" humans outside of Africa also miss the mark. (Note: when I say "human" I'm referring not to "modern human" but to a member of the genus Homo.) This story from March discusses a report of stone tools and cutmarked bone from India purportedly dating to 2.6 million-years-ago (MYA), blowing away the current earliest accepted evidence of humans outside of Africa (Dmanisi at 1.8 MYA) by about 800,000 years. With an increasing number of Oldowan assemblages dating to about 1.8-1.6 MYA are being reported outside of Africa (e.g., in China and Pakistan), would it be that surprising to find evidence a migration pre-dating 1.8 MYA? Probably not. Do the finds reported from India cement the case for human populations in South Asia at 2.6 MYA? Not yet: the fossils and tools reported from India so far (as far as I know anyway) don't have a context that allows them to be convincingly dated. My Conversation with Scott Wolter  Forbidden Archaeology (ANTH 291-002): It's going to worthwhile. Forbidden Archaeology (ANTH 291-002): It's going to worthwhile. I had a pleasant conversation with Scott Wolter yesterday. I emailed him to touch base about his participation in my class in the fall, and we ended up talking for about 45 minutes. It was the first time we've spoken and we had more to talk about than we had time to talk. We talked about the Wolter-Pulitzer partnership, of course, but I'm not going to go into the details of our discussion (I just invite you to read for yourself Pulitzer's bizarre word salad blog post from Wednesday containing his reference to me as "some back woods rural South Carolina Pseudo-Archaeologist who never worked in the field, but only learned from books"). My sense is that Wolter is someone with whom I can have a frank and vigorous discussion about the merits and interpretation of archaeological evidence and how it is used to evaluate ideas about the past. I'm looking forward to his participation in my class. My plan is to start a Go Fund Me campaign to raise money to fly him down here so he can interact with the students on a face-to-face basis. And now the movers are coming for my filing cabinets. And now my chair is gone. And now you are up-to-date.

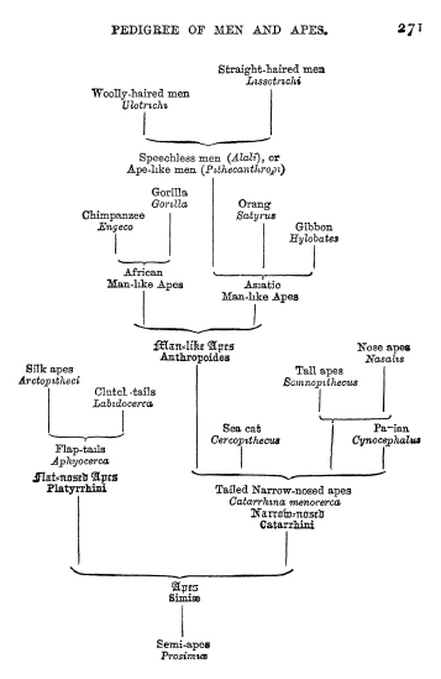

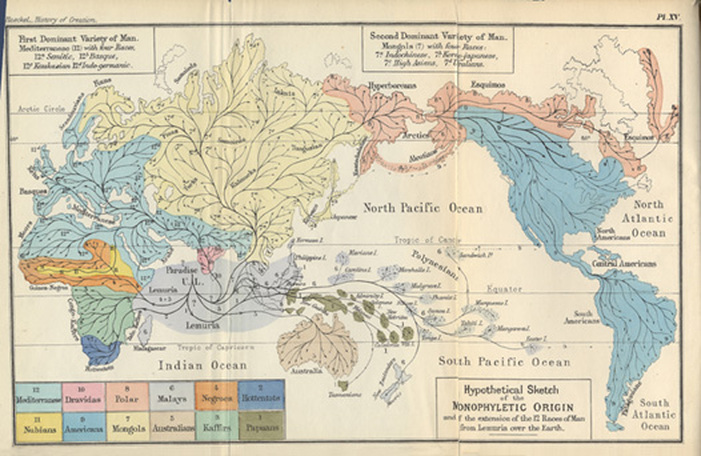

I've got a blogging backlog. It's the usual story of more things to write about than time to write about them. Before #Swordgate took the air out of the room, I was working on understanding how modern belief in giants was tied to Young Earth Creationism and indigenous American religious movements (see this post on Seventh Day Adventists and the Deluge Society). Tied to my interest in giants, I had started dabbling in understanding how the remains of Gigantopithecus (an actual animal that lived in east Asia) are incorporated into narratives about giants and Bigfoot (see this post about the lack of postcranial remains and this post about tooth size). I've been spending more of my blogging time writing about my Archaic research (i.e., the Kirk Project and, lately, an effort to compile a massive Eastern Woodlands radiocarbon database) than fringe stuff lately. There isn't time to keep all the balls in the air at once, but I intend to keep talking about all these things and more as I have the opportunity over the summer. This post about Ernst Haeckel and the lost continent of Lemuria is one I started a long time ago. I'm going to wrap it up and post it to get it out of my "draft" box. Ernst Haeckel (1834-1919) would easily make any reasonable list of the Top Ten Most Racist Anthropologists. A biologist by training, Haeckel regarded the various "races" of humans as being distinct species that evolved from some hypothetical, pre-language "primaeval ape-man" (Homo primeginius). He arranged his twelve living species of humans hierarchically. Unsurprisingly, Caucasians (including Indo-Germans) were at the top of the heap. While Haeckel was clearly a racist, it is not clear exactly how his ideas contributed to the rise of Nazism (see this essay for one treatment).  In Volume II of the 1887 English edition of The History of Creation (a German version is here) Haeckel laid out his evolutionary taxonomy of humans. He proposed a basic division between "straight-haired men" and "woolly-haired men,' the common ancestor of which was speechless "ape-like men," or Pithecanthrops. In other words, Haeckel thought the languages of "straight-haired men" and "woolly-haired men" emerged independently after these different species of humans diverged. While he was clearly thinking in evolutionary rather than creationist terms, Haeckel's (1887:293-294) description of the pre-language divergence of difference "species" of humans resonates with a polygenist perspective on human variation: "These Ape-like men, or Pithecanthropi, very probably existed towards the end of the Tertiary period. They originated out of the Man-like Apes, or Anthropoides, by becoming completely habituated to an upright walk, and by the corresponding stronger differentiation of both pairs of legs. The fore hand of the Anthropoides became the human hand, their hinder hand became a foot for walking. Although these Ape-like Men must not merely by the external formation of their bodies, but also by their internal mental development, have been much more akin to real Men than the Man-like Apes could have been, yet they did not possess the real and chief characteristic of man, namely, the articulate human language of words, the corresponding development of a higher consciousness, and the formation of ideas. The certain proof that such Primaeval Men without the power of speech, or Ape-like Men, must have preceded men possessing speech, is the result arrived at by an inquiring mind from comparative philology (from the "comparative anatomy "of language), and especially from the history of the development of language In every child ("glottal ontogenesis ") as well as in every nation ("glottal phylogenesis "). . . . As, according to the unanimous opinion of most eminent philologists, all human languages are not derived from a common primaeval language, we must assume a polyphyletic origin of language, and in accordance with this a polyphyletic transition from speechless Ape-like Men to Genuine Men." Notice that Haeckel's family tree classifies the ancestor of humans as an Asian ape closely related to gibbons and orangutans. Haeckel was writing at a time when fossil evidence of human evolution was still incredibly thin: the few Neanderthal remains that had been found in Europe were not well understood, and Eugene Dubois' (1891) discovery of fossils in Java (now classified as Homo erectus) was still in the future. In short, there was no consensus about what the fossils of a human ancestor would look like or where in the world they should be found. In this vacuum of fossil evidence, Haeckel relied on the study of linguistics of living peoples to reconstruct human evolution. If all of this sounds rather quaint and harmless, read on in Haeckel's treatise to understand the implications of his understanding of linguistic and physical variation among human populations (1887:307-310): "[The Ulotrichi, or woolly-haired men] are on the whole at a much lower stage of development, and more like apes, than most of the Lissotrichi, or straight-haired men. The Ulotrichi are incapable of a true inner culture and of a higher mental development, even under the favourable conditions of adaptation now offered to them in the United States of North America. No woolly-haired nation has ever had an important " history."" In Haeckel's view, differences in language clearly reflect innate biological differences in the cognitive capacities of different human groups, and, therefore, their actual degree of humanity. That is just about as racist as it gets. Wile Haeckel saw linguistic variation in human populations as polyphyletic (marking development since the divergence of humans species from a common ancestor), he recognized that the human lineage must ultimately be monophyletic (descended from a common ancestor) and therefore have some geographic place of origin. Turning to the question of where in the world the common ancestor of humans originated, Haeckel (1887:326) rejects the existing continents as the location of "Paradise" (i.e. "the cradle of the human race") and proposes that the lost continent of Lemuria makes the most sense: "But there are a number of circumstances (especially chorological facts) which suggest that the primaeval home of man was a continent now sunk below the surface of the Indian Ocean, which extended along the south of Asia, as it is at present (and probably in direct connection with it), towards the east, as far as further India and the Sunda Islands; towards the west, as far as Madagascar and the south-eastern shores of Africa. We have already mentioned that many facts in animal and vegetable geography render the former existence of such a south Indian continent very probable. (Compare vol i. p. 361.) Sclater has given this continent the name of Lemuria, from the Semi-apes which were characteristic of it. By assuming this Lemuria to have been man's primaeval home, we greatly facilitate the explanation of the geographical distribution of the human species by migration." At the time Haeckel was writing, the idea that there was a lost continent beneath the Indian Ocean made a lot of sense. While the 19th century concept of Lemuria (named after the lemurs of Madagascar) usefully explained the discontinuous distributions of some plants and animals, 20th century seafloor exploration and knowledge of plate tectonics showed that no such sunken landmass exists. There was no Lemuria, and the existence of such a place cannot be used to credibly frame ideas about human evolution and, consequently, the meanings of biological and linguistic variability among human populations.

This falsification of the idea of Lemuria is science in action. As racist as Haeckel was, I bet that he still would have adjusted his ideas about human evolution in the face of direct fossil evidence or the knowledge that there was no such thing as Lemuria. In regards the "paradise" of Lemuria, Haeckel (1887:325) acknowledged that "I must premise the remark that, in the present state of our anthropological knowledge, any answer to this question must be regarded only as a provisional hypothesis." In the absence of direct evidence, it is possible to construct multiple narratives to explain the past and what it has to do with the present. The lack of direct evidence allows many mutually-exclusive ideas to be simultaneously regarded as credible. Science works by developing lines of evidence that allows some of those ideas to be tested and potentially falsified. This is why Lemuria was a fine idea in the late 1800's but is a nonsense one now. And this is why what we now know about human evolution and variation shows Haeckel's ideas about different human "species" as the inherently racist constructs that they are. Science works by letting facts kill ideas. Lemuria went down in smoke a long time ago, as did the idea that there are deep biological/cognitive differences between modern human populations. If you are holding on to either of these ideas, you should ask yourself why. There were many other possible titles for this post. I will spare you a list and just give you the front runner: "An Hour of My Life I'll Never Have Back." Kent Hovind is a well-known Young Earth Creationist. In Federal prison for financial crimes since 2006 (see this article from Forbes), one of his first stops after being released this July was The Rundown Live, a Milwaukee-based talk radio program that bills itself as "Covering news and conspiracy that your local news won’t." Hovind was interviewed by self-proclaimed "researcher of giant human skeletons" Kristan Harris. The interview is here. A conspiracy-minded giant enthusiast interviewing a Young Earth Creationist? I thought I was in for a treat. Oh well - you can't win 'em all. Hovind regurgitates all the usual assertions of Young Earth Creationsm: the Earth was created in six days about 6000 years ago; dinosaurs were really giant lizards that were documented historically as "dragons"; the fossil "record" doesn't really tell us anything about the past; no-one has ever seen macro-evolution in action so it couldn't possibly have happened; all radiometric dating methods are nonsense; paleontologists and other evolutionary scientists are all stupid; etc. Hovind's assertions are pretty old hat these days, and many of his favorite arguments have been publicly rejected by other creationists.  Screenshot from the movie "Zombeavers:" a man holds his own foot, which has been removed from his body by a zombie beaver. Screenshot from the movie "Zombeavers:" a man holds his own foot, which has been removed from his body by a zombie beaver. Yawn. So much for my Friday night. My wife was out of town and I was on my own during the sliver of time between getting the kids to bed and being asleep myself. When I was in a similar situation a few weeks ago, I spent that precious "me" time watching Zombeavers, a 2014 film about how "A fun weekend turns into madness and horror for a bunch of groupies looking for fun in a beaver infested swamp." It would probably be unfair to directly compare the plausibility of Hovind's tale with what unfolds before our eyes in Zombeavers, so I won't do it. I wouldn't want to be unfair. Anyway, the one useful thing I heard in the interview was a succinct statement of the "doctrine of degeneracy" that I've seen associated with Young Earth Creationism in several other places. As I have discussed previously, this view asserts that:

Giant enthusiasts who are also Young Earth Creationists (such as Joe Taylor of the Mt. Blanco Fossil Museum and Chris Lesley of the Greater Ancestors World Museum) link together the existence of large extinct animals (that we can understand via the fossil record), the long human lifespans reported in the Old Testament, and the biblical mentions of “giants” as in Genesis 6:4. In this case, bigger is better: humans and that existed closer to the time of creation were larger in size and closer to perfection than the humans of today. The running down of the clock since creation has resulted in humans and animals that are smaller, simpler, and farther from perfection. Hovind sums up that view nicely at about 38:50 minutes into the interview: "You see the Bible says Man was made in God's image. Adam could name all the animals and walk, talk, and get married on the first day. He was fully formed, a fully loaded computer. He spoke every language in the world (well there was only one). But he was probably off the charts IQ compared to us today. So Man started off smart, and we're getting smaller, dumber, and weaker as time goes by, I believe. And I think the evolution theory teaches exactly the opposite: we started off like a chimpanzee and we're getting bigger, better, and smarter. There's absolutely no evidence for that at all." In order to allow that baloney to stick to the wall, you have to flatten time and reject all evidence and methods that point to our planet being much, much older than 6000 years and you have to equate the giants of the Bible with the "good" side of God's creation rather than corrupt beings set upon preventing humanity from reaching salvation. (The Bible doesn't say anything directly about Adam's stature - you've got to go elsewhere for that). Thus the giants of Young Earth Creationists are categorically different from the sinister homosexual demon-giants of Steve Quayle and the alien-seeded giants of Ancient Astronaut theorists (Hovind categorically dismisses the possibility of extraterrestrial intervention in the human past at about 40:10 in the interview). In terms of Friday night entertainment value, the win goes to my time spent watching a guy pretend a zombie beaver chewed off his foot. The so-called Nephilim Mounds Conference is going on right now in Ohio -- maybe something interesting will come out of that, but I'm not holding my breath. What giant enthusiasts really need to do (besides take me up on my offer to participate in my class) is to organize a conference where they debate the logic, evidence, and implications of the very, very different views of "giants" that exist. I would pay to see advocates of the various interpretations of giants attempt to triangulate the Young Earth Creationist, Nephilim Whirlpool, and Ancient Alien views of what "giants" actually were and are. They appear to me to be largely mutually exclusive, and I'm not sure how they could be reconciled. I don't think that there will ever be such a Giants Summit, however, because I think there is little appetite among giant enthusiasts to subject their ideas to scrutiny. I'm probably better off hoping for a Zombeavers 2. I'm pretty sure at least some of the beavers escaped at the end. They were pretty hard to "kill," of course, since they were zombies. Fingers crossed there's a sequel in the works in case I ever have another evening to waste.

This morning's announcement of the first results from the Rising Star Expedition did not disappoint: a 35-page open access paper with 47 authors (Berger et al. 2015) describing fossil remains (Homo naledi) from at least 15 individuals recovered since 2013 from a cave in South Africa, and another paper by Dirks et al. (2015) describing the physical context of the fossils. I'm friends with several of the authors, and I am so happy for them both personally and professionally. And I'm jealous. But we'll leave that aside for now.

There are so many things that are awesome about this project that it's hard to even know where to start. If you don't follow paleoanthropology closely, you may not fully grasp how unusual this discovery is, how novel the approach to excavation and analysis was, and how @#!$&*% badass the results are. The story of the Rising Star Expedition is the Mad Max: Fury Road of paleoanthropology. I hope we start seeing more movies like this. This is the largest single hominin fossil assemblage yet discovered in Africa, it is remarkable well-preserved, and it was analyzed and reported upon in record time. Two years from discovery to publication is blisteringly fast in the world of paleoanthropology (the publication of Ardipethecus ramidus, a 4.4 million-year-old putative hominin from Ethiopia, famously took over 15 years). Speeding up initial analysis by inviting a crowd of young, hungry scholars to contribute to the work (hence the 47 authors on the first paper) was a masterful stroke by project leader Lee Berger. The Rising Star Expedition has convincingly demonstrated the utility of a new paradigm that challenges traditional notions about how paleoanthropology should be done and what constitutes an appropriate pace for analysis and publication. Bravo on that front: totally @#!$&*% badass.

The initial findings/interpretations/conclusions from Rising Star are also pretty @#!$&*% badass. Here are a few that jump out to me as important during a first quick pass through the paper: Mosaic of Primitive and Derived Features. According to the authors, the skeletons of Homo naledi preserve a mixture of human-like and australopithecine-like features unlike that seen in any other fossil remains: H. naledi has humanlike manipulatory adaptations of the hand and wrist. It also exhibits a humanlike foot and lower limb. These humanlike aspects are contrasted in the postcrania with a more primititive or australopith-like trunk, shoulder, pelvis and proximal femur (Berger et al. 2015:2).  Two views of the hand of Homo naledi (Figure 6 from Berger et al. 2015). The hand was discovered still articulated. Two views of the hand of Homo naledi (Figure 6 from Berger et al. 2015). The hand was discovered still articulated.

The appearance of a different "mosaic" of primitive and derived features was also described by Lee Berger for the Australopithecus sediba fossils (a rather late gracile australopithecine from South Africa), highlighting the difficulty understanding extinct hominins based on single bones or very fragmentary skeletons. The skeleton of sediba appeared to have such a strange mixture of features that some researchers suggested the remains were actually those of two different species mixed together. I think it will be pretty difficult to make that argument for the naledi remains because of the number of specimens and their apparent morphological homogeneity. The implications of the mosaic aspects of the Rising Star fossils will have to be dealt with rather than dismissed. The features that we associate with being human apparently did not come together as a "package deal."

South, Not East? Identifying naledi as a member of our genus means it is a potential human ancestor. The center of gravity in the study of the emergence of the genus Homo has been in East Africa for many decades. But if naledi is ancestral to our lineage, what does that mean for the fossils of possible human ancestors found in East Africa? Do they get pushed out of the lineage? Do they have to leave the adult table at Thanksgiving and go sit with the little kids? There is no possible fossil assemblage from East Africa of early Homo that compares with the one from Rising Star in terms of size and its potential to tell us about so many aspects of the skeleton. I think that means that, unless you want to just assume that East Africa is where everything important happened, naledi has to be dealt with in any serious discussion of the origins of Homo. And that brings us once again to the "species" issue. What Does "Species" Mean? I wrote a little bit about species concepts inthis post from May when a new species (Australopithecus deyiremeda) was proposed for the fossil of another purported human ancestor. My point in that post was that if we're imagining that each "species" is a reproductively isolated population, naming a new species has a lot of implications that I think are tough to justify based on fragmentary fossils. It's most problematic when species are named based on very little physical evidence. There's a lot of material from Rising Star, however, and I would guess that many people are comfortable with creating a new taxon based on the amount of material that Berger et al. (2015) have analyzed. That's fine. But I'm still wondering what is meant by the term "species." I didn't see a definition of "species" in the paper (it's possible I missed it), but I did see this passage in the National Geographic story about Rising Star that came out today: "Berger himself thinks the right metaphor for human evolution, instead of a tree branching from a single root, is a braided stream: a river that divides into channels, only to merge again downstream. Similarly, the various hominin types that inhabited the landscapes of Africa must at some point have diverged from a common ancestor. But then farther down the river of time they may have coalesced again, so that we, at the river’s mouth, carry in us today a bit of East Africa, a bit of South Africa, and a whole lot of history we have no notion of whatsoever." I like the metaphor of a braided stream, but it sounds a lot more like we're describing populations within a single biological species rather than species-level divergences. Once the "species" streams diverge through reproductive isolation, how could they ever converge again? Using a biological species concept, they can't. We may need to give things names so we can talk about them and compare them, but it seems to me, again, that our taxonomic terminology and practices are ill-suited and maybe counter-productive for actually describing and understanding the patterns and processes that we're interested in. But There's No Date! There are no dates associated with the Rising Star fossils. That means we really have no independent handle on where in time they go, which means it's hard to use them to test specific hypotheses about the patterns, processes, and history of human evolution. Without dates it will really tough to understand how they might fit in with the East African materials, or sediba, or the recently-announced 3.3 million-year-old stone tools from Kenya. Wherever these fossils "go" in time they'll make a splash, but we don't know right now where the ripples will be. I hope we get some information about that soon. Was naledi Burying Its Dead? Surely one of the most controversial interpretations of the Rising Star assemblage will be that it accumulated through intentional disposal of the dead. That's the conclusion of this paper by Dirks et al. (2015): "Preliminary evidence is consistent with deliberate body disposal in a single location, by a hominin species other than Homo sapiens, at an as-yet unknown date." That lack of a date is especially painful here. The earliest claims that I know of for regularized treatment of the dead come from the site of Sima de los Huesos (Atapuerca), where the bodies of 28 individuals were thrown into a cave in Spain around 400-500 thousand years ago. Evidence for the patterned, ritualized treatment of the dead at Atapuerca fits well with other possible signs of a cognitive emergence about half a million years ago, including the shell of similar age announced last year that was apparently carved by Homo erectus and evidence of the removal of flesh from the Bodo cranium at about 600,000 years ago. If the Rising Star fossils date to the origins of Homo, as the researchers suggest, and if the assemblage accumulated through intentional cultural behavior, it will push ritual treatment of the dead much farther back in time than we have ever considered. Two million years ago? I bet there are probably people out there who still don't even think Neanderthals were burying their dead. That's sure to spark some arguments. Jealousy aside, it's going to be great to watch what happens next. I'm sure there will be more results from Rising Star (hopefully soon), and I'm sure there will be a lot of reaction to what came out today. It's a totally @#!$&*% badass project with totally @#!$&*% badass results. This is a great time to be paying attention to human evolution - maybe the best ever. Fingers crossed we get an announcement of australopithecine DNA soon.

Berger, L., Hawks, J., de Ruiter, D., Churchill, S., Schmid, P., Delezene, L., Kivell, T., Garvin, H., Williams, S., DeSilva, J., Skinner, M., Musiba, C., Cameron, N., Holliday, T., Harcourt-Smith, W., Ackermann, R., Bastir, M., Bogin, B., Bolter, D., Brophy, J., Cofran, Z., Congdon, K., Deane, A., Dembo, M., Drapeau, M., Elliott, M., Feuerriegel, E., Garcia-Martinez, D., Green, D., Gurtov, A., Irish, J., Kruger, A., Laird, M., Marchi, D., Meyer, M., Nalla, S., Negash, E., Orr, C., Radovcic, D., Schroeder, L., Scott, J., Throckmorton, Z., Tocheri, M., VanSickle, C., Walker, C., Wei, P., & Zipfel, B. (2015). , a new species of the genus from the Dinaledi Chamber, South Africa eLife, 4 DOI: 10.7554/eLife.09560

If you're at all interested in human evolution and not currently living in a cave somewhere, you're probably aware that there's an announcement coming from the Rising Star Expedition tomorrow morning. Since its discovery in 2013, the Rising Star Cave has produced thousands of remains of fossil hominids. A large team was assembled to excavate and analyze the remains, and many of us have been waiting for the last couple of years for publication of the results. Tomorrow could potentially be a very interesting day.

If a "couple of years" from discovery to publication sounds like a long time to you, you probably haven't been paying very close attention to paleoanthropology. A couple of years is absolutely lightning fast, especially given the volume of materials that have come out of the cave. The Rising Star project has the potential to be remarkable because of both the information it will provide (whatever that is) and the way it was done. The approach that Lee Berger and colleagues took -- quick analysis and publication and the involvement of many early career scientists -- provides a model of a new way of doing things. I hope that the results are spectacular and make plain the utility of fast-tracking fossil finds and making the process accessible. Another "new" thing in anthropology that is generating buzz today is the announcement of the planned launch of SAPIENS in January of 2016. According the website, "SAPIENS is an editorially independent online publication of the Wenner-Gren Foundation dedicated to popularizing anthropological research to a worldwide audience. Through news coverage, features, commentaries, reviews, photo essays, and more, SAPIENS will share the field’s most exciting, relevant, thought-provoking, and unconventional ideas." Anthropology needs more active engagement with the public, and I hope this turns out to be as good as it sounds. I do not believe anthropologists are using nearly all of the available tools that we have to communicate to the public what it is that we do. I hope that this adds one. On the "out with the old" side, National Geographic announced today that it is shifting to for-profit status. To me, this seems like a natural step in the ongoing degradation of the National Geographic brand. Remember the hub-bub over the National Geographic program Diggers? And then yesterday I read this National Geographic piece titled "7 Ancient Mysteries Archaeologists Will Solve This Century." Most of the "mysteries" involved things like finding lost cities, excavating the tombs of famous people, or figuring out the Nazca lines. It's a piece that feeds into numerous misconceptions about what it is that most archaeologists actually do, celebrating the spectacular, headline-grabbing discovery rather than the actual systematic attempt to use material evidence to understand truly important questions about the human past. That's a bummer coming from National Geographic. How long will it be until we see them producing sensational content so that they can compete with the fake documentaries about mermaids on Discovery and the ancient aliens on History? The ways in which science is done and communicated to the public are changing. I've got my fingers crossed that we're going to start doing some things differently. And I can't wait to see what came out of the Rising Star Cave. |

All views expressed in my blog posts are my own. The views of those that comment are their own. That's how it works.

I reserve the right to take down comments that I deem to be defamatory or harassing. Andy White

Email me: [email protected] Sick of the woo? Want to help keep honest and open dialogue about pseudo-archaeology on the internet? Please consider contributing to Woo War Two.

Follow updates on posts related to giants on the Modern Mythology of Giants page on Facebook.

Archives

January 2024

Categories

All

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed