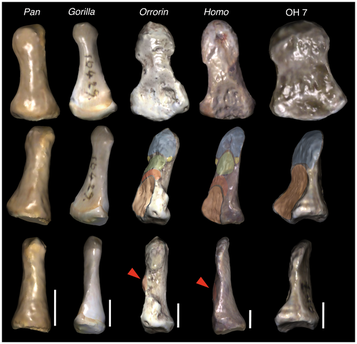

In their paper, titled "New Species from Ethiopia Further Expands Middle Pliocene Hominin Diversity" (Nature 521:483-488), Yohannes Halie-Selassie and colleagues use the word "species" 17 times but provide no explicit definition of the term. What is a "species"? What are the implications of defining a "new species" of hominid?

Like so many other things, it depends. There exists a smorgasbord of different species concepts to choose from. A "typological species," for example, is a classification based on the co-occurrence of shared features, while an "evolutionary species" is defined based on the integrity of an ancestral lineage (without branching, there is no new species). A "biological species" is generally defined as a group of organisms that can breed with one another but not with other groups of organisms. In other words, a biological species is reproductively isolated from all other biological species. The biological species concept is perhaps the one most frequently applied in biology, especially to living populations of plants and animals.

I think a "biological species" is also what most people, paleoanthropologists included, mean when they talk about "species" of hominids.

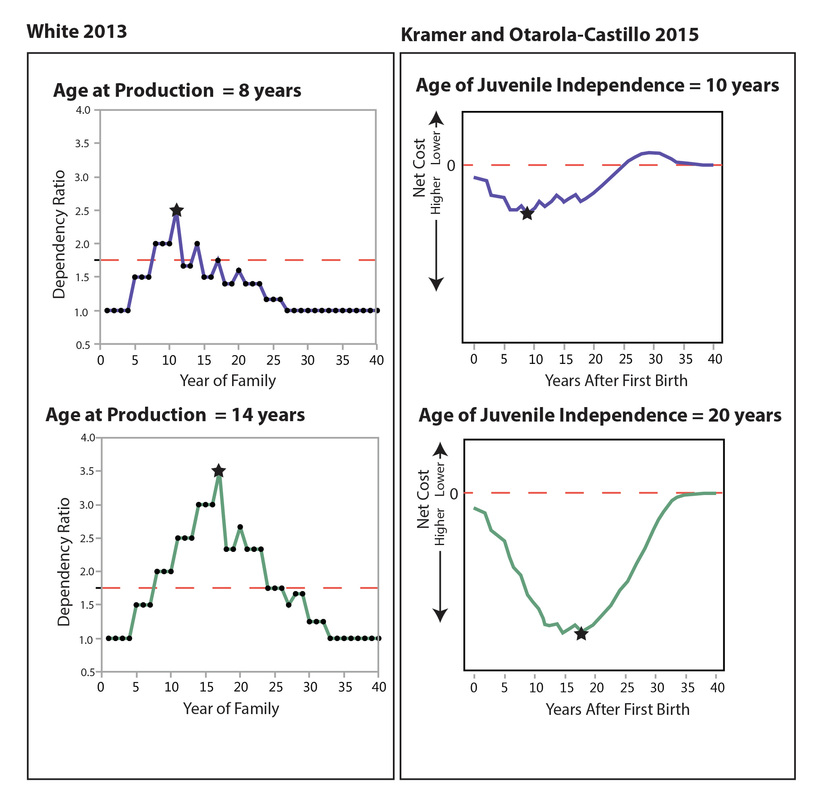

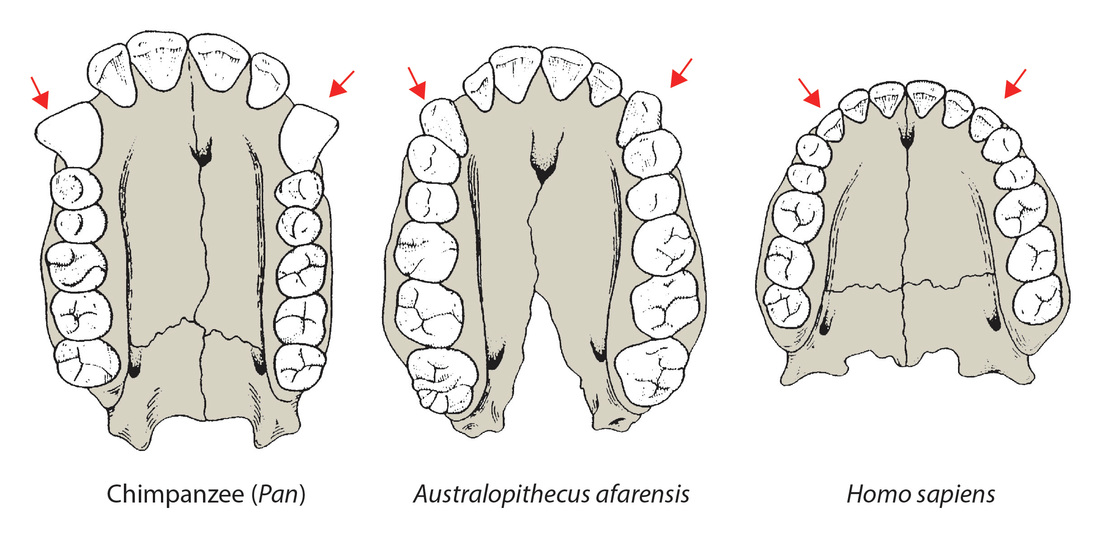

The distinctions among the various species concepts are not just academic when they're applied to fossil hominids. They have implications for our notions about what variability means in the fossil record and how we interpret that variability in terms of the patterns and processes of human evolution. Because reproductive isolation is the entire basis of the biological species concept, individuals in a biological species (by definition) could not and did not interbreed with any of their contemporaries outside their own species. There cannot be multiple, co-existing species of human ancestors: a "new species" is either a human ancestor or somewhere off on a side-branch of our evolutionary family tree. The discovery of a human ancestor that pushes someone else off onto a side branch is much more exciting that the discovery of another non-contender. You can see that in the enthusiasm of headlines about Australopithecus deyiremeda such as "Doubt cast on Lucy's place in human evolution" and "New hominid discovery older than Lucy raises more questions on human ancestry." They might as well read "Don't let the door hit you in the ass on way out, Lucy."

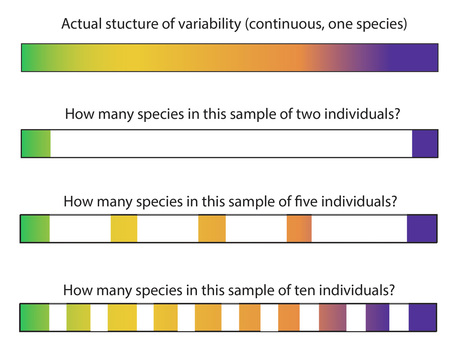

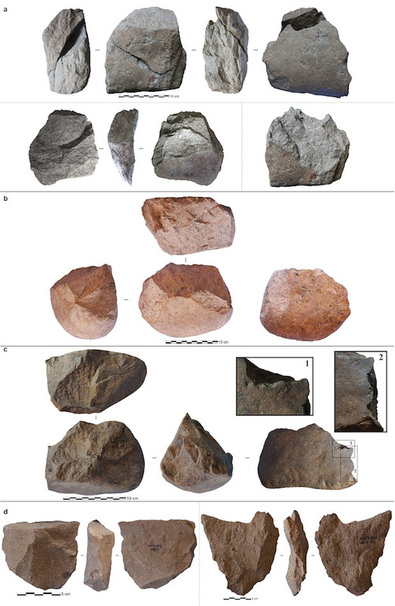

I'm not an expert on paleoanthropology, and I've never directly analyzed or attempted to describe or classify the remains of a fossil hominid. But I am someone who regularly attempts to describe variability (mostly in lithic artifacts) and make sound interpretations about what that variability means. In any case, when you're looking at continuous variability, you can split all you want. There is easily detectable variability in just about everything not produced by a machine, so ultimately it's no great feat to break continuous variability down into as small of groups as you want (groups of one, if that makes you happy). But what do those groups mean? That's a hard question to answer without having a sample of a decent size that let's you investigate how the variability you're looking at is structured. That's why I'm a fan of trying to understand how variability is structured before trying to create groupings that have some analytical value.

So I'm very skeptical of the reality of the number of named species that currently inhabit the hominid family tree. How many are there now? Twenty? Thirty? More? I wonder what would happen if we started fresh and re-analyzed all the Pliocene and Pleistocene hominid fossils discovered over the last 120 years. What would the structure of variability look like, and how would we interpret that variability if we erased all the existing species names and the historical legacies of discovery that accompanied them and based our groupings on patterns of variability across time and space? Who knows. I also wonder how many "species" of domestic dogs paleoanthropologists would define given a sampling of their bones.

Anyway, splitters be splittin,' and there's not much I can do about it. When I taught my 200-level Human Origins class last year, I made the decision to focus not on the minutiae of "species" in the fossil record, but on what various lines of evidence could tell us about the timing, processes, causes, and effects of changes in human anatomy and behavior over evolutionary time. We talked about species concepts and why they matter, and I gave my class my opinion that we're too quick to name new species and perhaps too reluctant to first look at what variability might mean outside the constraints of a species-level classification. Is Homo antecessor a legitimate "biological species"? Is the Homo erectus/ergaster division useful? If we know that Neanderthals and Homo sapiens exchanged DNA, why are we still calling them separate species?

Maybe I've wrongly identified the dominant species concept that is active in the background of paleoanthropological thought. Maybe a new name isn't meant to assume reproductive isolation and all that that implies. If I've gotten it wrong, please correct me. Maybe I missed something somewhere. In my own published work, I've been asked to provide clarifying definitions for such controversial terms such as "household," "process," "model," and "projectile point." President Clinton famously debated the meaning of the word "is." Is it too much to ask for a clarifying definition of "species" when we define a new one?

RSS Feed

RSS Feed