Her basic premise, if I understand it, is that one can create a "phylotechnical tree" of actions associated with different kinds of percussion. Following Leroi-Gourhan (1971), her use of the term "percussion" includes actions such as sawing, chopping, cutting, and puncturing. All of these different actions would ultimately have had a common origin in what de Beanue calls "thrusting percussion" (using one object to forcefully strike another with the intent of cracking or smashing it). The primacy of thrusting percussion is supported by its ethnographically-observed use among chimpanzees: some chimps crack hard fruits by smashing them between a hammer and an anvil. Thus, de Beaune argues, thrusting percussion would have been utilized by the earliest hominids and preceded the more formalized stone tool technologies we can recognize in Oldowan.

How, why, and when did thrusting percussion, perhaps first used solely as an action employed to crack animal or vegetable materials, begin to be used to used to crack stone? Those are the questions that can potentially be addressed directly by the assemblage reported from LOM3 (and hopefully more to be found in the future).

To the "when" question, LOM3 answers "by at least 3.3 million years ago." It's hard to imagine that the earliest identified example of something actually marks its earliest occurrence, so it's probably safe to presume that the behaviors that created LOM3 were present sometime prior to 3.3 MYA.

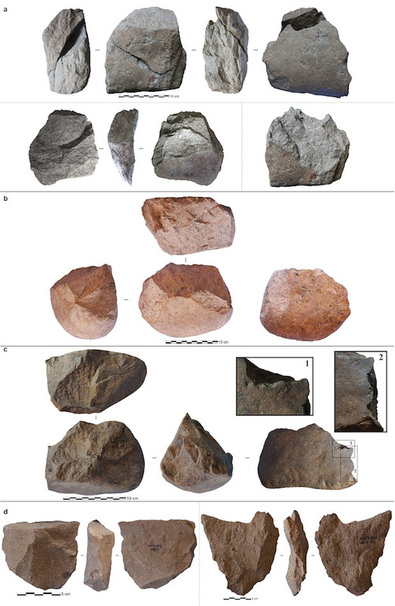

The first publication on 149 pieces of worked stone from LOM3 also gives us some insight into the "how" question. According to the authors (pp. 311-312), the assemblage contains 83 cores (pieces of stone used for the removal of flakes) and 35 flakes. The remainder of the stone pieces are interpreted as "potential anvils" (n=7), "percussors" (n=7), "worked cobbles" (n=3), "split cobbles" (n=2), and indeterminate fragments (n=12). You can see 3D digital models of some of the artifacts here.

Core from the LOM3 site (image source: http://www.nature.com/nature/journal/v521/n7552/full/521294a.html)

Core from the LOM3 site (image source: http://www.nature.com/nature/journal/v521/n7552/full/521294a.html)

"The dimensions and the percussive-related features visible on the artefacts suggest the LOM3 hominins were combining core reduction and battering activities and may have used artefacts variously: as anvils, cores to produce flakes, and/or as pounding tools. . . . The arm and hand motions entailed in the two main modes of knapping suggested for the LOM3 assemblage, passive hammer and bipolar, are arguably more similar to those involved in the hammer-on-anvil technique chimpanzees and other primates use when engaged in nut cracking than to the direct freehand percussion evident in Oldowan assemblages." (p. 313)

That sounds to me like a description that's pretty consistent with a manufacturing strategy based largely on chimp-like "thrusting percussion," and perhaps exactly what one would expect to precede Oldowan based on de Beaune's analysis.

What about the "why" question? What caused hominids to start using thrusting percussion to produce tools? Answering that question is tougher than addressing the "when" and "how" questions.

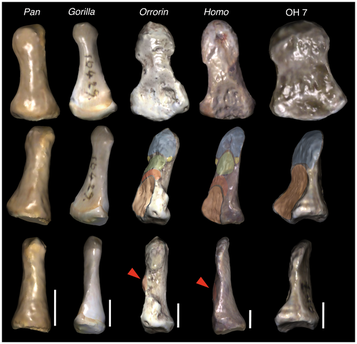

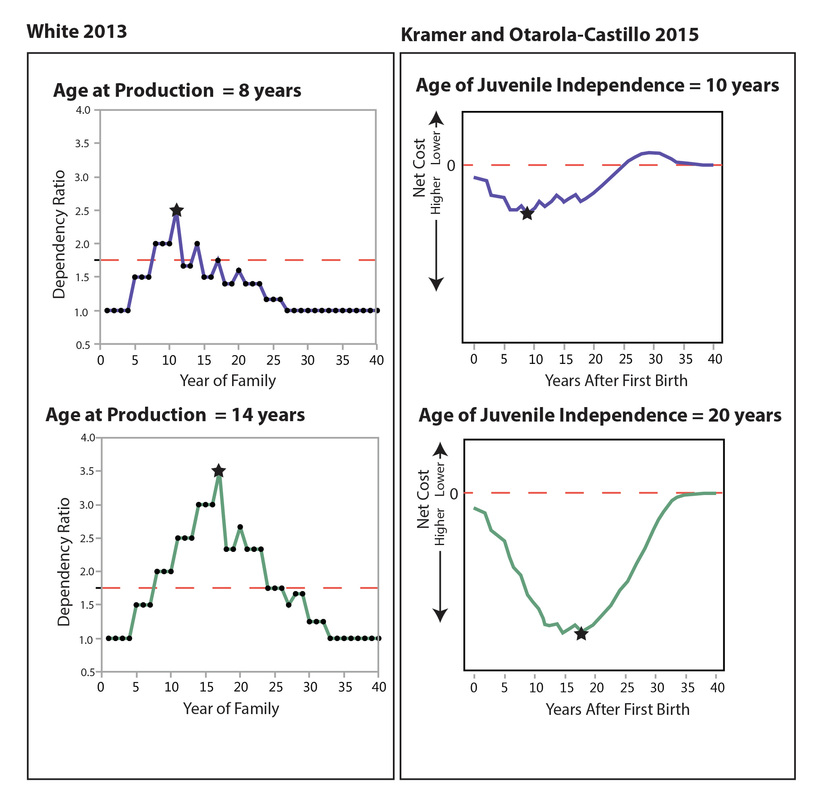

I don't think it has much to do with a change in physical anatomy -- specifically that of the hand -- for three inter-related reasons. First, as I discussed before, I think there's a lot of evidence that suggests that hands with the capacity for human-like precision gripping were widespread among early hominids, including the australopithecines of around 3.3 MYA. (See also this comment on australopithecine hands that just came out in Science today.) Second, as discussed by de Beaune (p. 141-142), the physical actions required to smash one rock with another are not all that different than the actions required to smash a piece of fruit on an anvil: no new anatomy was even required to shift the "target" of the percussion to stone. Third, even with the limitations imposed by their hand anatomy, chimpanzees can be taught to use freehand percussion to make stone tools (see this video of Kanzi, for example).

If the "invention of technology" (meaning, in this case, chipped stone technology) wasn't dependent upon a change in anatomy, what about a change in cognition? Again following Leroi-Gourhan, de Beaune (2004:142) discusses the nature of the distinction between using a hammerstone to smash something to process food and hitting a stone with another stone to produce a cutting edge:

"While these activities involved related movements, that of intentionally splitting a cobble to produce a cutting tools, although "exceedingly simple," was in [Leroi-Gourhan's] view eminently human in that it "implied a real state of technical consciousness.""

Maybe there does have to be a cognitive change to explain the shift to producing and using stone tools. But, as we know from the Kanzi example, there's nothing lacking in the chimp brain that prevents them from making and use simple chipped stone tools when they're taught. But, as far as we know, they have to be taught (the last time I checked, though, humans also need to be taught to do it).

Surely an important thing to understand about the shift to using stone-on-stone percussion to make stone tools is what that shift gets you: a tool with a cutting edge unlike anything that exists in nature. A sharp-edged flake can be used for what de Beaune calls "linear resting percussion" (cutting and chopping). You can do a lot of things with an edged tool that you can't do with a blunt one (and that you can't do with your teeth if, like australopithecines, you lack the large canines of chimps and many other non-human primates). You can sharpen a stick. You can grate and slice plants. And you can cut meat from bones and disarticulate an animal carcass by severing ligaments. We have some direct evidence of this last activity in the form of the 3.4-million-year-old cutmarked bones reported from Dikkika, Ethiopia, in 2010. Maybe the battlefield of the hunter-scavenger debate, now several decades old, will be reinvigorated by a transplantation from the Pleistocene to the Pliocene.

Does the emergence of chipped stone technologies during the Pliocene signal an adaptive shift, a cognitive shift, or both? With the publication of the LOM3 tools and the announcement last week of a new fossil australopithecine from about the same time period and neighborhood, East Africa 3.3 million-years-ago sounds like a pretty interesting place to be. If, as suggested by ethnographic data from chimps, gorillas, and orangutans, the capacity to use tools is really a homology that extends deep into the Great Ape lineage, it's probably not fair to refer to the production of chipped stone tools as the "invention of technology." But it is a watershed nonetheless. The shift to using one set of tools (hammers and anvils) specifically to make other, qualitatively different tools (cutting implements) that potentially open up new subsistence niches and eventually (possibly) become involved in the feedbacks between biology, technology, and culture which are entangled in the emergence of our genus is something worth knowing about: who did it? why? what were the tools used for? what changed as a result?

The assemblage from LOM3 opens up a tantalizing window on those questions. In those 149 pieces of stone, we have evidence of a stone tool production strategy that used "passive hammer" techniques to produce cutting tools, somewhere in time much closer to the dawn of stone tool production than anything called Oldowan. Judging by the size of the cores and flakes, the technique appears to have been more dependent on brute force than finesse. The results, however -- the creation of cutting tools from a natural setting that provided none -- may have been transformational. I look forward to seeing how the data from the small LOM3 assemblage get incorporated into models of human evolution, and I hope that people working in East Africa are already busy finding more sites. And I hope that people working outside of East Africa are actively searching for stone tools in Pliocene deposits. It's a great time to be following paleoanthropology.

RSS Feed

RSS Feed