|

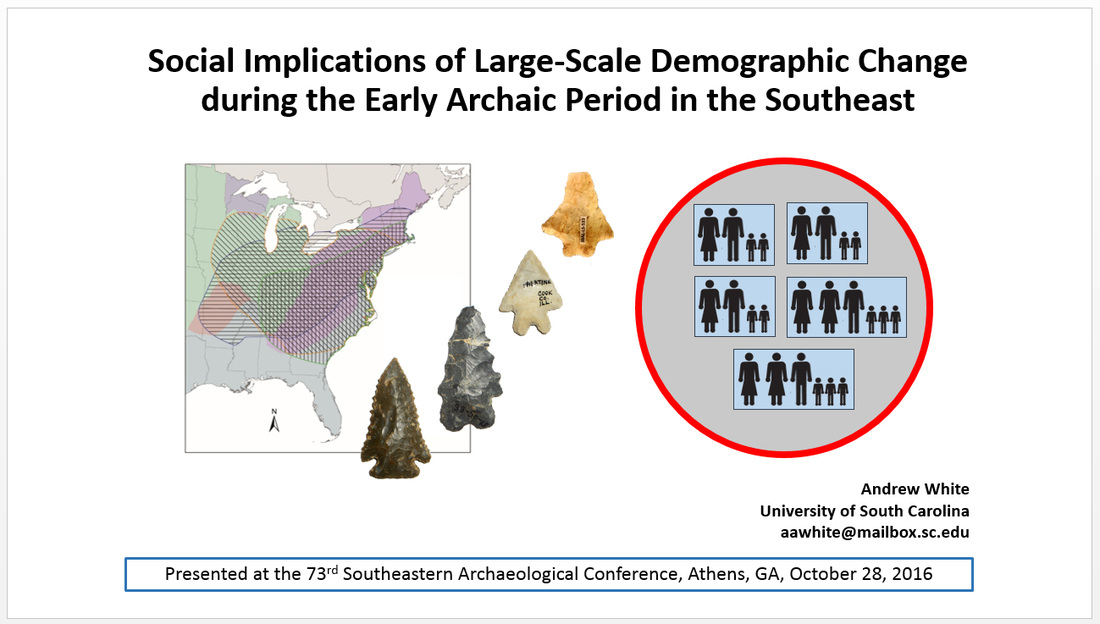

I've loaded a pdf version of my 2016 SEAC presentation "Social Implications of Large-Scale Demographic Change During the Early Archaic Period in the Southeast" onto my Academia.edu page (you can also access a copy here). Other than a few minor alterations to complete the citations and adjust the slides to get rid of the animations, it's what I presented at the meetings last Friday. I tend to use slides as prompts for speaking, so some of the information that I tried to convey isn't directly represented on the slides. There's enough there that you can get a pretty good idea, I hope, of what I was going for.

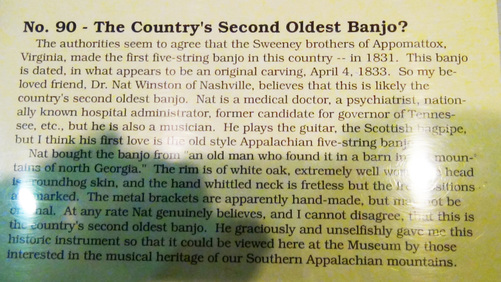

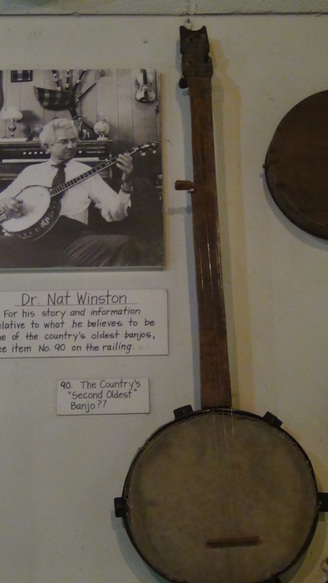

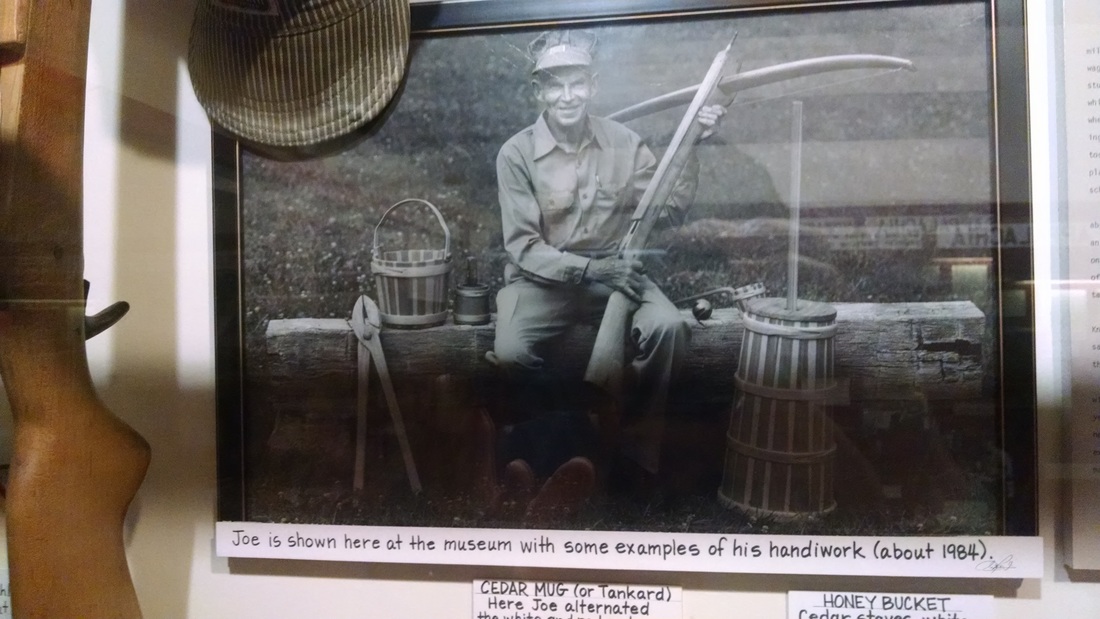

Last week, my answer to the question "how many blog posts discussing banjos will you write in August?" would have been "zero." Today marks number three. That shows you just how hard it is to predict the future.  This is going to be a short one. I wanted to follow up on the yesterday's discussion of who "invented" the banjo. The banjo display in the Museum of Appalachia states that "the Sweeney brothers of Appomattox, Virginia" made the first five-string banjo in this county -- in 1831." Joel Sweeney was a minstrel performer who popularized the banjo among white audiences. I'm still trying to figure out exactly what Sweeney is being credited with "inventing," since African American banjos that pre-date Sweeney had the same basic design as the "modern" five-string banjo: a membrane stretched over a skin, a stiff neck, and several strings, one of which was a "drone" string. Was it that Sweeney used a wooden frame instead of a gourd? Or that he used a fretted neck? Or that he standardized the five-string arrangement (African American banjos had a varying number of strings)? If we're going to give Sweeney credit for making the first banjo in the country because he used a wooden frame instead of a gourd, it seems like we should also give credit for creating a new instrument to whoever made the bedpan banjo, the toilet seat guitar, and the horse jaw fiddle that are also on display in the museum. This painting titled "The Old Plantation" (attributed to John Rose, ca. 1785-1795) shows an African slave playing a four-string (fretless?) banjo on a South Carolina plantation. The banjo appears to have a stretched membrane and a short drone string. As far as I can tell, it's the oldest depiction of a banjo in North America. Yesterday I wrote a brief post about my visit to the Museum of Appalachia in eastern Tennessee. My main point was that it's a fantastic museum, different from anything I've seen before (and I've seen a lot of museums). You can read that post for my somewhat soppy overview paragraph about what makes this museum so interesting (to me, anyway).  The first building that you visit at the museum is called the "Hall of Fame." The sign in the entryway explains pretty well what the goal is. This is one of the most interesting places in the museum, introducing you to the people and culture of the region though an incredibly varied display of personal artifacts, photographs, and anecdotes, with many of the placards written out by hand and signed by the museum's founder, John Rice Irwin. You can read about Viola Carter's cowbell, look at Felix "Casey" Jones' devil's head, and see a fiddle made from a horse mandible. There's a lot in the "Hall of Fame," and the slower you move the more you will absorb. I was on medium speed, still having a lot of miles to cover that day to get back to Columbia. So I didn't read every word or every display. Some of the things I bring up here may well be in the museum, somewhere. One of the things that makes this museum great, I think, is its affection for its subject: it's a museum about Appalachia and Appalachians, created by Appalachians. It is kind of an "inside" ethnography that embraces the distinctiveness of Appalachia, communicating and often celebrating characteristics that outsiders might see as strange, even embarrassing or depressing. The museum doesn't try to make an argument, or even to explain, it just gives you a chance to run your fingers over the fabric so you can maybe get some idea of its patterns, weaves, and textures. Pride in the distinctiveness of Appalachian culture emerges loud and clear. Two items that jumped out at me from the "Hall of Fame" displays were the crossbow and the banjo. I didn't know much about the history of either of these items in American material culture. I left the museum with the impression that both were home-grown in Appalachia. A little online research, however, suggests the introduction of both to the region was via enslaved peoples from West Africa (the case for the African origin of the banjo is stronger than that of the crossbow). This is fascinating for several reasons, not least of which is that it's an interesting historical case of the transmission of technologies (one musical and one subsistence-related) between two very different groups. Appalachia remains one of the whitest regions of the county. The Crossbow  The Museum of Appalachia has at least two crossbows on display, along with stories about the men who made and used them. I had never before heard of the tradition of "mountain crossbows," and there isn't a whole lot of information online (at least not that I've found so far). I ran across a discussion on this forum and learned that there's a short section on crossbows in the book Guns and Gunmaking Tools of Southern Appalachia by none other than John Rice Irwin (future purchase). Based on the few things I've been able to read so far, the consensus seems to be that crossbows were made and used for hunting because their use did not require manufacture of bullets or purchase of powder (or cartridges, etc.). In other words, they were inexpensive to operate. Th poverty angle makes sense for the "why" question. But the question of why crossbows were used doesn't explain how they came to be used. Where did the crossbow tradition come from? It's possible it came from Europe along with the people (predominantly "Scotch-Irish") who settled the region: while the crossbow had largely disappeared from military use by the mid-1500's (replaced by firearms), the weapons were apparently still used for civilian hunting until the 1700's (unfortunately the only source I've got on that so far is Wikipedia). One alternative to the "brought them along" scenario that I've seen mentioned is the idea that the use of crossbows was transferred first from the early Spanish explorers in the southeast to Native American peoples, and then later from descendants of those Native Americans to the European settlers of Appalachia. Another is that crossbow technology was transferred to Native Americans and/or Appalachian Europeans from West Africans brought to the New World as slaves. In his paper "Notes on West African Crossbow Technology," Donald Ball argues that a good case can be made for transfer of crossbow technology from Africans to Native Americans: "Available descriptions of crossbows as they occur in western Africa and among Native Americans in the southeastern United States are sufficient to postulate the transmission of a type of this weapon into the New World by slave populations and the adoption of an altered form of that technology by various indigenous tribal groups. Despite featuring a crude facsimile of the gunstocks used by their Anglo neighbors, the utilization of a simplified notch string release system (less the split stock and release peg exhibited in west African examples) may be interpreted as a modification of a much older design which had effectively been abandoned in Europe by the time of the New World entrada yet continued to flourish western Africa until at least the 1920s (Powell-Cotton 1929). Though it is but a small example of transplanted technology, further research on this topic may potentially further reveal a heretofore unheralded example of African-American contributions to the cultural mosaic of the material folk culture of the United States." Ball observes that known Appalachian crossbows have a "trigger" mechanism more like western European crossbows than the "string-catch" system seen in West African and Native American crossbows. I don't know how many examples of nineteenth-century Appalachian, Native American, and West African crossbows are known (my guess is not many), but it would be really interesting to find out what we know know about the age and provenience of New World examples and what could be learned by compiling data about their construction. I'm guessing someone (perhaps Donald Ball) has already done that work. I'm going to track down his "n.d." paper that he lists as "submitted to Tennessee Anthropologist." The Banjo The West African origin of the banjo is firmly established. Like many other people (I presume), I was under the false impression before last week that the banjo was an indigenous American invention. When I looked at the fascinating display of home-made and "early" banjos at Museum of Appalachia, I didn't see anything that made me question that. The museum displays what they claim is possibly the "County's Second Oldest Banjo" (dated to 1833), specifying that the oldest known 5-string banjo was constructed in 1831 by the Sweeney Brothers.  A few minutes searching online reveals that the history of the banjo in America doesn't start with the Sweeney Brothers -- not by a long shot. Joel Sweeney (1810-1860) was a minstrel performer who is known as the first white person to play the banjo on stage. He popularized the banjo among white audiences and played a prominent role in developing the five-string banjo, but he didn't invent the banjo or build the first one in the country. Historical documents make it clear that enslaved populations from West Africa brought the tradition of the "banjo" with them, creating instruments in the New World from whatever suitable materials could be found and utilized. Thomas Jefferson described slaves playing an instrument called the banjar in Notes on the State of Virginia (1781): "The instrument proper to them in the Banjar, which they brought hither from Africa, and which is the original of the guitar, its chords being precisely the four lower chords of the guitar." Here is an NPR story on some recent research trying to trace the African origins of the banjo. The five-string banjo is a fundamental component of bluegrass music, an indigenous American art form with a center of gravity in Appalachia. As far as I'm aware, the other stringed instruments that contribute to the distinctive sounds of bluegrass (e.g., the fiddle, the guitar, the mandolin) have roots in western Europe, the ancestral home of most of the settlers of the region. It's fascinating to me both that (1) the distinctively American sound of bluegrass owes much to the combination of European and African instruments and (2) I didn't already know that. The oldest banjo in the country wasn't made by Joel Sweeney, but by some African whose name we'll never know. It would be amazing if any of those pre-Sweeney, African New World banjos still survives, considering they were probably made with all (or mostly) perishable parts. I'm wondering if archaeology can contribute anything to fleshing out this story. Yesterday I spent several hours at the Museum of Appalachia in Clinton, Tennessee. I found this place to be intensely interesting and, frankly, at times surprisingly moving. I'm not sure how much time I'll have to write over the next couple of weeks: I'm back home again from the last trip of the summer and we've got a lot to do as a family to transition to the school year. I wanted to put this post here as reminder of some of thoughts I had about Appalachia as I crossed the region several times this summer. I hope that I can circle back around and develop some of my thoughts at some point (no guarantees). I became aware of the Museum of Appalachia through it's entry in Roadside America, which described the museum as having a "seemingly endless supply of oddities" including a wood burl devil's head and a Civil War-era perpetual motion machine. I would've enjoyed the museum just for those things, but the fact is that it is really much more than a collection of oddities. Many of the items in the museum (which sprawls across 65 acres and several buildings filled with artifacts) are attached directly to stories about the people connected to the material culture. The items (such as homemade crossbows, polka dotted furnishings, whittled toys, and unique musical instruments) and the narratives evoke peoples' lives and experiences in a way that I have never seen before in a museum, blending the personal and historical to create (in me, at least) the sense that I knew these folks. My own family history, flirting with the fringes of Appalachia, probably contributed to that sense of familiarity. This museum makes history both big and small at the same time, and gives a voice to the textures, rhythms, and trajectories of people, societies, and ways of life that don't get much play in the "big" narratives of history -- a remarkable achievement. For now, I'm just going to post some photos I took.  A display of home-made banjos. The museum has what it claims may be the second-oldest banjo in the country, dating to 1833 (I think). Because of its association with bluegrass music, the banjo is often thought to be an indigenous American instrument. There are multiple racial elements to the introduction and spread of the banjo, however. I don't know much about it yet, but the banjo was apparently brought to the Americas by slaves from West Africa. Appalachia is largely white ("Scotch-Irish"), and I didn't see much mention of African Americans either in connection with musical traditions or any other aspects of Appalachian life.  There were millstones and grinding stones all over the place. Some of the millstones were composite, but many were one piece with a round hole in the center. This stack of stone cylinders made me wonder how the millstone holes were created -- did they use some kind of tubular drill? So far I've found no evidence of that online, and I'm guessing the stone cylinders are from cores taken for the purposes of mineral exploration. Any thoughts? One of the reasons I'm interested in this is because of the "fringe" claim that circular holes in hard stone (e.g., in ancient Egypt) could not have been created without some kind of advanced technology, despite the existence of copper tubes used in conjunction with sand to drill though granite. |

All views expressed in my blog posts are my own. The views of those that comment are their own. That's how it works.

I reserve the right to take down comments that I deem to be defamatory or harassing. Andy White

Email me: [email protected] Sick of the woo? Want to help keep honest and open dialogue about pseudo-archaeology on the internet? Please consider contributing to Woo War Two.

Follow updates on posts related to giants on the Modern Mythology of Giants page on Facebook.

Archives

January 2024

Categories

All

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed