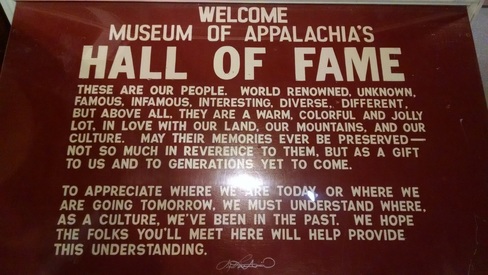

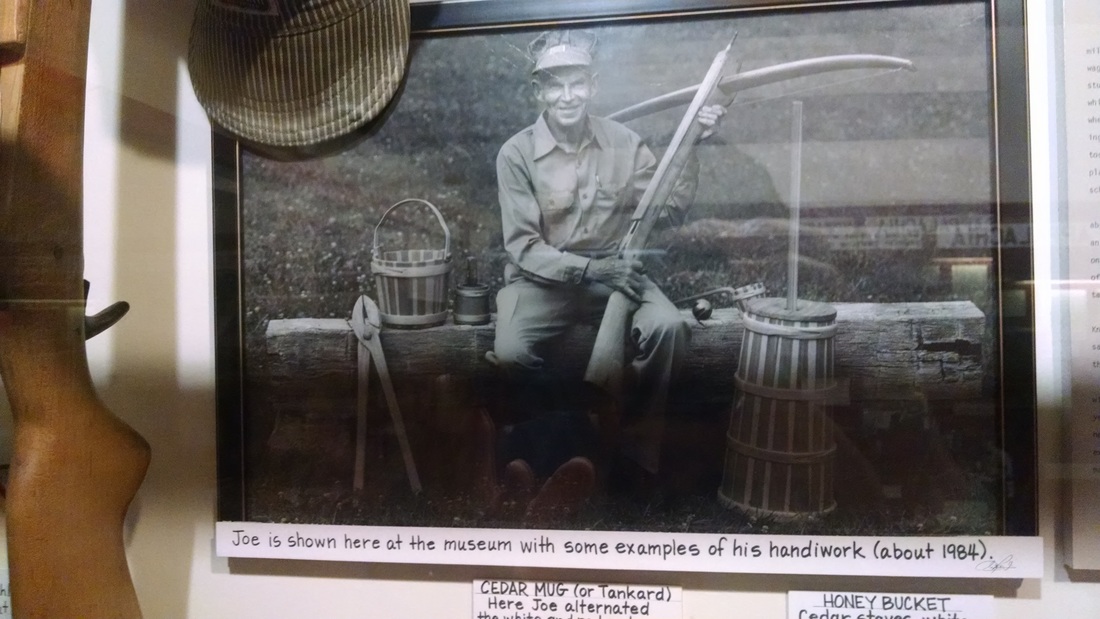

There's a lot in the "Hall of Fame," and the slower you move the more you will absorb. I was on medium speed, still having a lot of miles to cover that day to get back to Columbia. So I didn't read every word or every display. Some of the things I bring up here may well be in the museum, somewhere.

One of the things that makes this museum great, I think, is its affection for its subject: it's a museum about Appalachia and Appalachians, created by Appalachians. It is kind of an "inside" ethnography that embraces the distinctiveness of Appalachia, communicating and often celebrating characteristics that outsiders might see as strange, even embarrassing or depressing. The museum doesn't try to make an argument, or even to explain, it just gives you a chance to run your fingers over the fabric so you can maybe get some idea of its patterns, weaves, and textures.

Pride in the distinctiveness of Appalachian culture emerges loud and clear. Two items that jumped out at me from the "Hall of Fame" displays were the crossbow and the banjo. I didn't know much about the history of either of these items in American material culture. I left the museum with the impression that both were home-grown in Appalachia. A little online research, however, suggests the introduction of both to the region was via enslaved peoples from West Africa (the case for the African origin of the banjo is stronger than that of the crossbow). This is fascinating for several reasons, not least of which is that it's an interesting historical case of the transmission of technologies (one musical and one subsistence-related) between two very different groups. Appalachia remains one of the whitest regions of the county.

The Crossbow

Based on the few things I've been able to read so far, the consensus seems to be that crossbows were made and used for hunting because their use did not require manufacture of bullets or purchase of powder (or cartridges, etc.). In other words, they were inexpensive to operate. Th poverty angle makes sense for the "why" question.

But the question of why crossbows were used doesn't explain how they came to be used. Where did the crossbow tradition come from? It's possible it came from Europe along with the people (predominantly "Scotch-Irish") who settled the region: while the crossbow had largely disappeared from military use by the mid-1500's (replaced by firearms), the weapons were apparently still used for civilian hunting until the 1700's (unfortunately the only source I've got on that so far is Wikipedia).

One alternative to the "brought them along" scenario that I've seen mentioned is the idea that the use of crossbows was transferred first from the early Spanish explorers in the southeast to Native American peoples, and then later from descendants of those Native Americans to the European settlers of Appalachia. Another is that crossbow technology was transferred to Native Americans and/or Appalachian Europeans from West Africans brought to the New World as slaves. In his paper "Notes on West African Crossbow Technology," Donald Ball argues that a good case can be made for transfer of crossbow technology from Africans to Native Americans:

"Available descriptions of crossbows as they occur in western Africa and among Native Americans in the southeastern United States are sufficient to postulate the transmission of a type of this weapon into the New World by slave populations and the adoption of an altered form of that technology by various indigenous tribal groups. Despite featuring a crude facsimile of the gunstocks used by their Anglo neighbors, the utilization of a simplified notch string release system (less the split stock and release peg exhibited in west African examples) may be interpreted as a modification of a much older design which had effectively been abandoned in Europe by the time of the New World entrada yet continued to flourish western Africa until at least the 1920s (Powell-Cotton 1929). Though it is but a small example of transplanted technology, further research on this topic may potentially further reveal a heretofore unheralded example of African-American contributions to the cultural mosaic of the material folk culture of the United States."

Ball observes that known Appalachian crossbows have a "trigger" mechanism more like western European crossbows than the "string-catch" system seen in West African and Native American crossbows. I don't know how many examples of nineteenth-century Appalachian, Native American, and West African crossbows are known (my guess is not many), but it would be really interesting to find out what we know know about the age and provenience of New World examples and what could be learned by compiling data about their construction. I'm guessing someone (perhaps Donald Ball) has already done that work. I'm going to track down his "n.d." paper that he lists as "submitted to Tennessee Anthropologist."

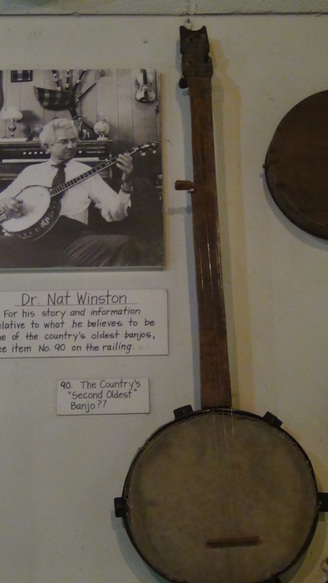

The West African origin of the banjo is firmly established. Like many other people (I presume), I was under the false impression before last week that the banjo was an indigenous American invention. When I looked at the fascinating display of home-made and "early" banjos at Museum of Appalachia, I didn't see anything that made me question that. The museum displays what they claim is possibly the "County's Second Oldest Banjo" (dated to 1833), specifying that the oldest known 5-string banjo was constructed in 1831 by the Sweeney Brothers.

"The instrument proper to them in the Banjar, which they brought hither from Africa, and which is the original of the guitar, its chords being precisely the four lower chords of the guitar."

Here is an NPR story on some recent research trying to trace the African origins of the banjo.

The five-string banjo is a fundamental component of bluegrass music, an indigenous American art form with a center of gravity in Appalachia. As far as I'm aware, the other stringed instruments that contribute to the distinctive sounds of bluegrass (e.g., the fiddle, the guitar, the mandolin) have roots in western Europe, the ancestral home of most of the settlers of the region. It's fascinating to me both that (1) the distinctively American sound of bluegrass owes much to the combination of European and African instruments and (2) I didn't already know that.

The oldest banjo in the country wasn't made by Joel Sweeney, but by some African whose name we'll never know. It would be amazing if any of those pre-Sweeney, African New World banjos still survives, considering they were probably made with all (or mostly) perishable parts. I'm wondering if archaeology can contribute anything to fleshing out this story.

RSS Feed

RSS Feed