Discussion and debate about interpretation of the anatomical remains of Homo naledi (i.e., what is it) and the context of those remains (how did they get there) continues in both traditional scientific journals and online. This is fascinating to watch, as the online element adds a new dimension to the "standard model" of paleoanthrnopological discourse (paralleling, perhaps, departures from the "standard model" of fieldwork, publication, and analysis marked by the Rising Star Expedition). I wrote about initial reaction to the Rising Star results here. You can get hooked into the latest debate -- concerned with whether manganese deposits on the bones show that the "chamber" the bones were found in was once open to light -- on John Hawks' blog.

Brad Lepper's column in Sunday's Columbus Dispatch discussed the Wyandotte Nation’s Cultural Center (Wyandotte, Oklahoma), describing exhibits that embrace the prehistoric cultural-hisotorical timeline developed by archaeologists but rename the periods with Wyandotte names and incorporate them into a Wyandotte narrative. Lepper writes:

"What I find particularly significant about this exhibit is that the Wyandotte Nation considers the culture history developed by archaeologists to be useful for telling their story. Also, by applying their own names to the various cultural periods, the Wyandotte take ownership of that history."

Very interesting story.

This climate change timeline lets you graphically scroll through 22,000 years of human-environment interaction. It depicts changes in the mean temperature of the earth at a scale that demonstrates how abnormally sudden and severe the warming trend has been over the last 100 years. The depiction is simple, requires no advanced math or imagination to understand, and nicely makes the point. Bravo.

Many of us are watching for results from excavations at Point Rosee, Newfoundland, a site identified as a possible pre-Columbian Norse habitation site based on analysis of images from satellites. The last I read, nothing that would definitively indicate a Norse presence at the site had been located. That doesn't mean it's not there, of course, and that doesn't mean that there aren't possibly other Norse in other parts of the region. This is a fun story to watch from my perspective because it's got the attention of both academic archaeologists and those on the "fringe" who are hungry for any piece of evidence that they think will legitimize their claims. This is a good demonstration both of how actual archaeology is used to search for empirical evidence to evaluate a claim/interpretation: either the Norse were at the site or they weren't -- so how can we tell? We go and look and do the work properly, that's how.

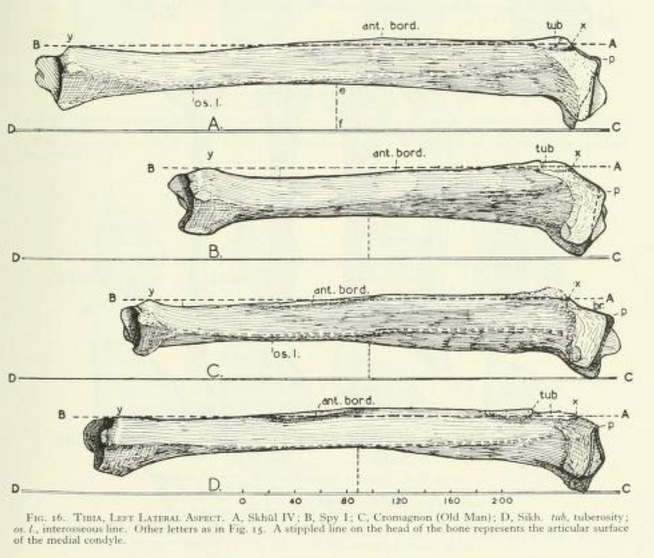

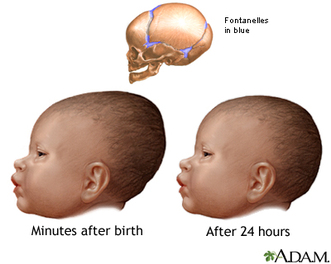

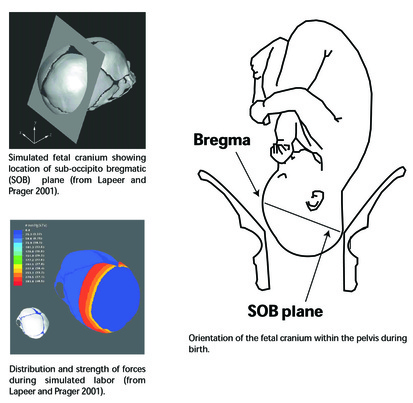

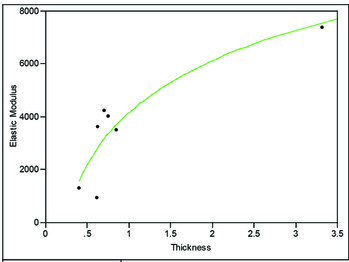

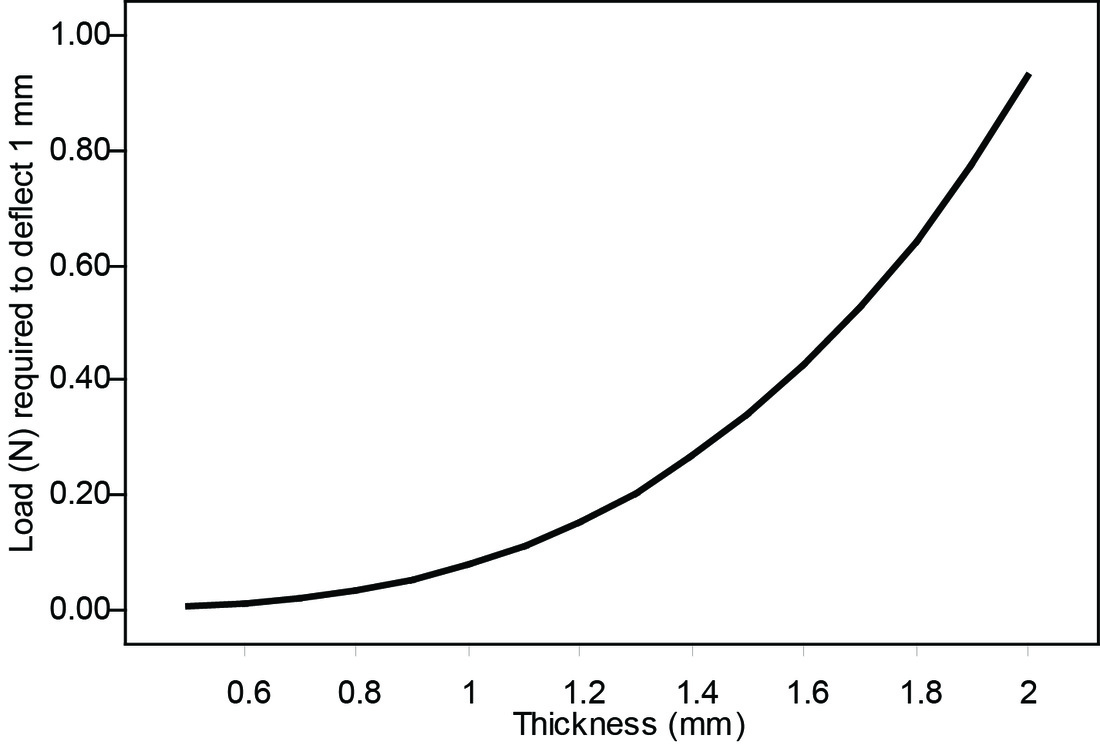

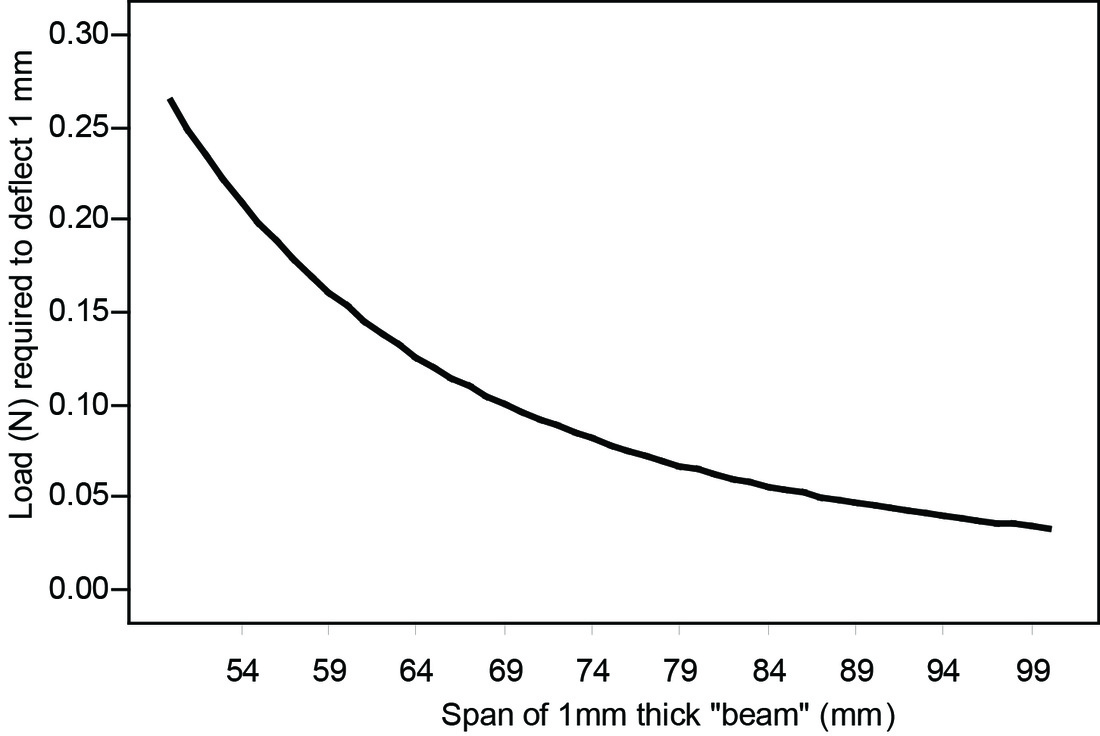

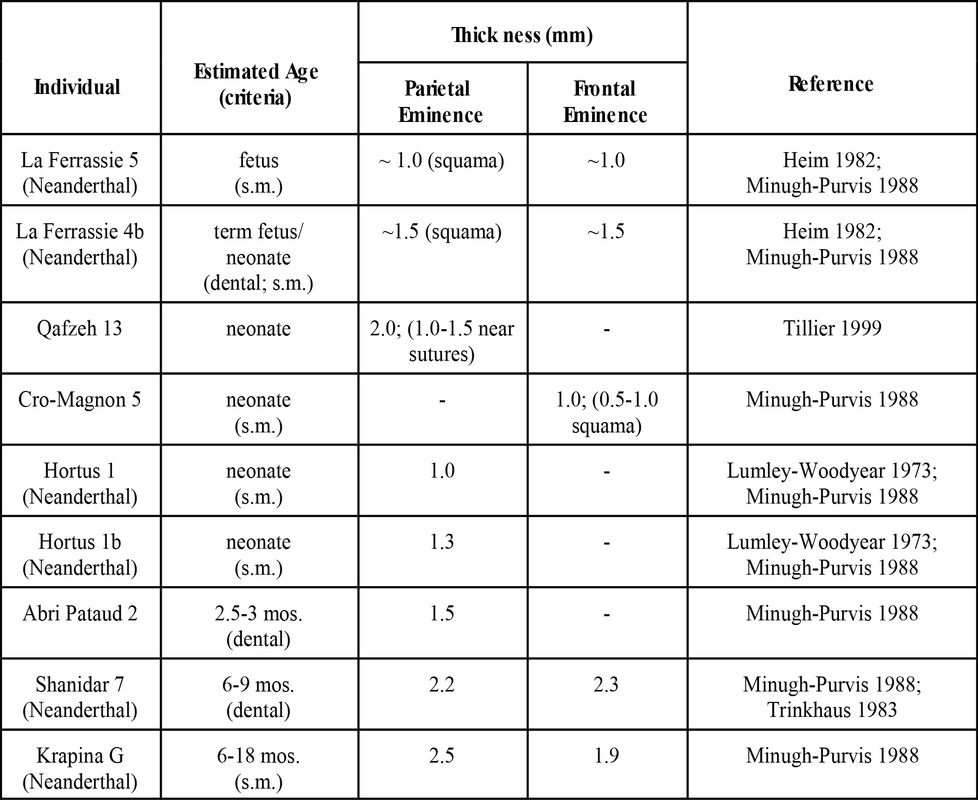

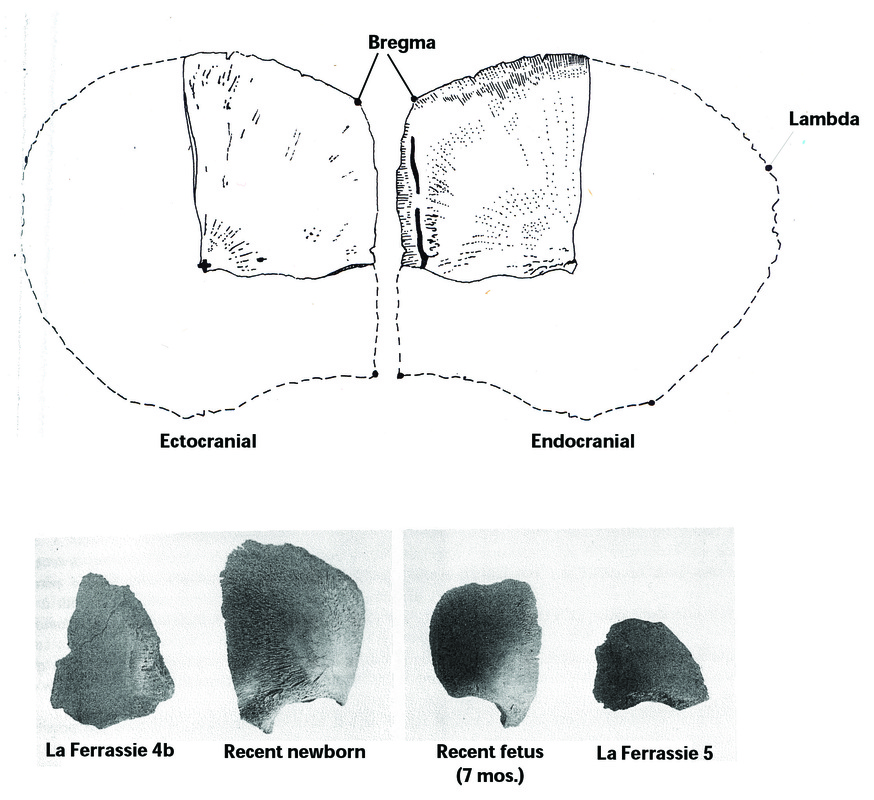

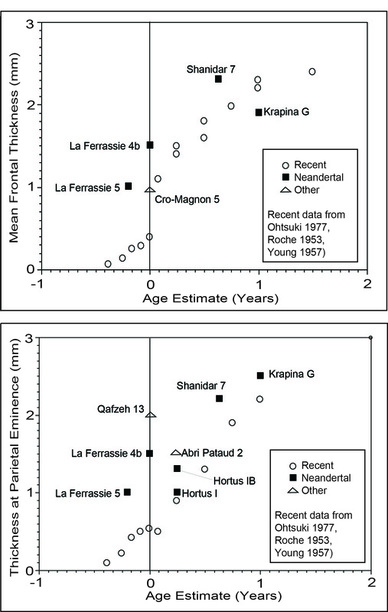

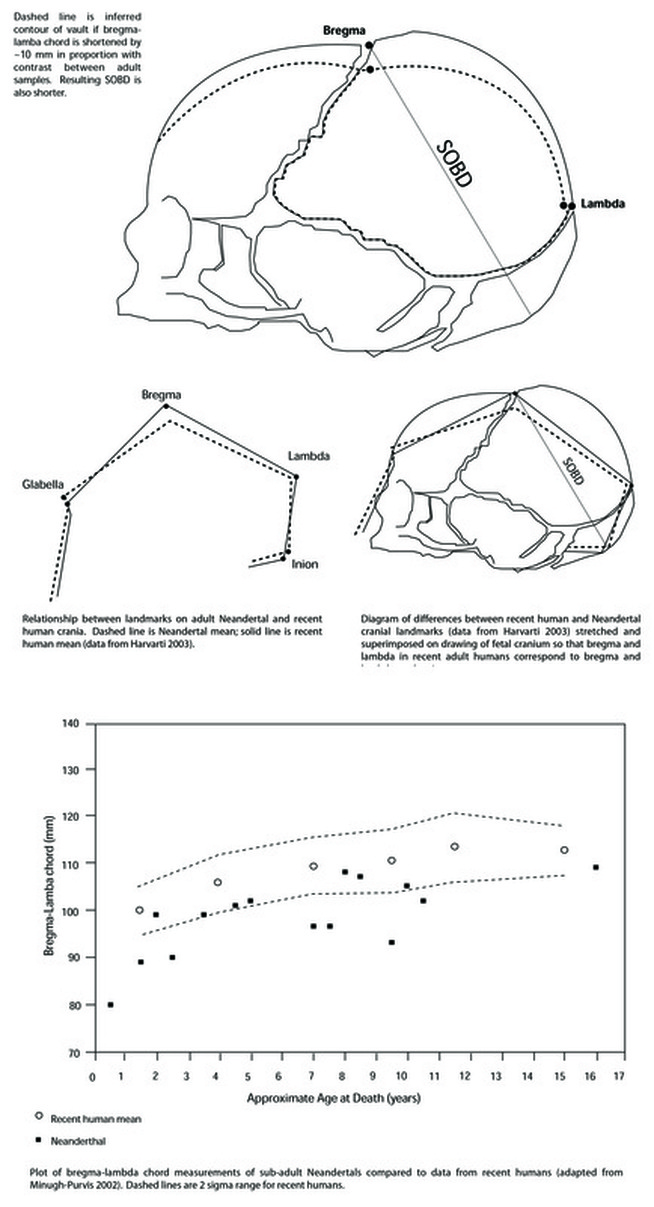

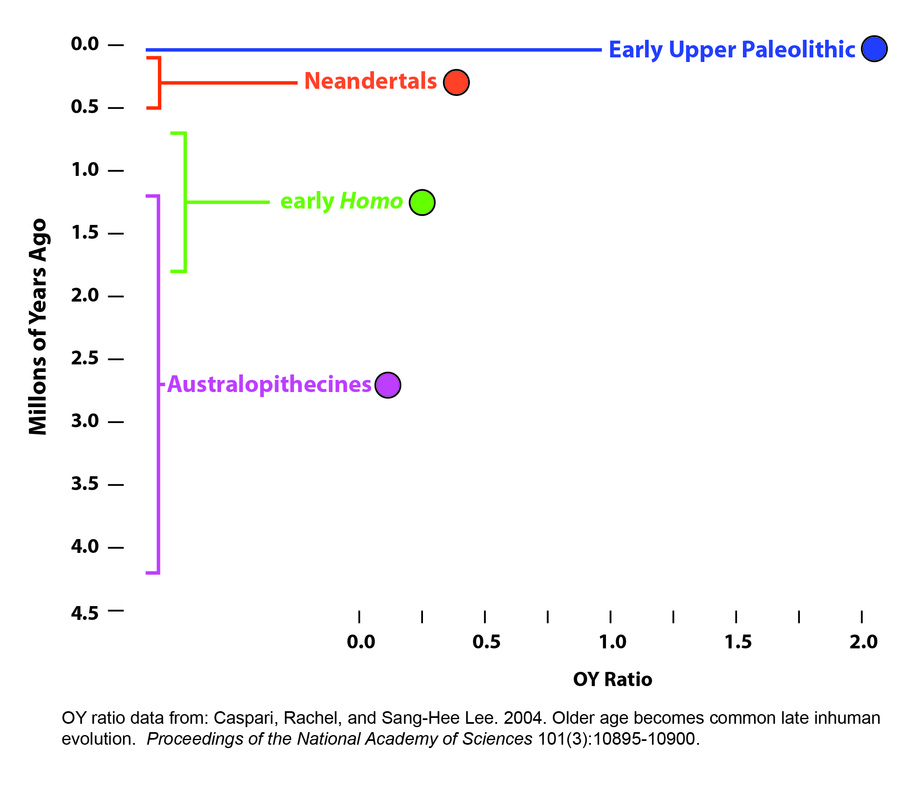

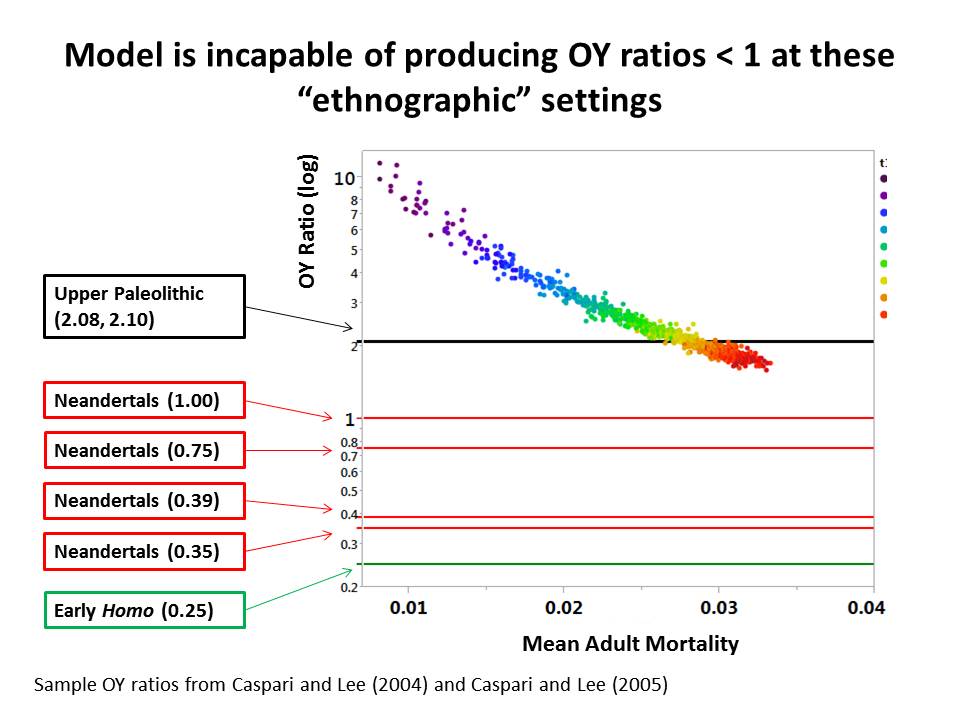

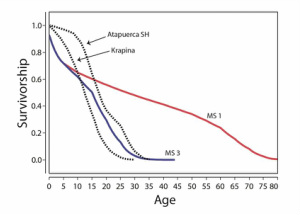

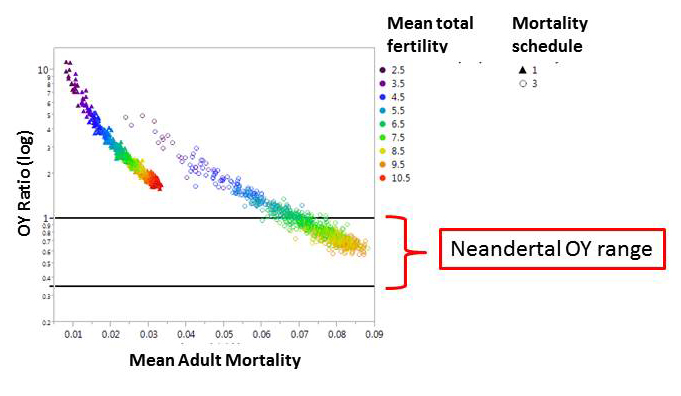

It's not my primary line of work, but I'm very interested in the understanding the deep prehistory of human families. That interest has several dimensions. While I was in graduate school at Michigan I did a project where I collected data on parietal thickness of every Late Pleistocene infant I could find to try say something about birth among those populations. I've done some modeling work (e.g., described here and here) trying to understand the relationships between fertility, mortality, and family size/composition among Middle Paleolithic humans. It's exciting when new infant/child remains are announced, such as the parietal from this 7-9-year-old Neanderthal child from Spain. There have been probably been others in recent years that I'm not aware of, so I'll have to do a drag net again if I'm able to focus on this topic in any serious way.

Finally, there's this Smithsonian article about depictions of medieval knights fighting snails. It pretty much speaks for itself.

RSS Feed

RSS Feed