Boy was I wrong about that.

As a scientist, it has been amazing (and not in a good way) to watch the various levels of government field the patchwork of responses that has gotten us to where we are today. Watching what was unfolding in Italy was like having a crystal ball, and yet those at the top levels of our government chose to . . . what? Fill in the blank yourself.

Things could have been much different. If we had used our headstart and data from other countries to get a legitimate testing program up and running . . . If we had used that time to ramp up production of the PPE and medical equipment that it was obvious we would need . . . If we had figured out how to use technology to track the spread . . . If we had done those things and had the leadership and the guts to go on complete lockdown early, we could have shut this down and gotten the situation under control before there were hundreds of thousands of cases and tens of thousands of deaths. We would have been out of the woods much sooner, with much less economic pain. But instead, we are where we are. It's not that no-one saw this train coming. It's that we didn't have the leadership and collective intelligence to figure out how to step out of the way.

You know when you yell at the idiot in the horror movie not to open the door to the basement? That's every scientist in this country a month ago.

I am thankful that I still have my job and that my family is in relatively good shape. No-one is sick, we're not going to go hungry, and we can pay our bills. My wife and I are doing the best we can to keep our two kids in some kind of routine that involves school work and exercise. I'm getting done what I need to as far as my job. We're all working to help keep my wife's business afloat in the face of all the government bungling of the "rescue" plan that's supposed to help her pay her bills while she's forced to close. No-one is sleeping well and the house is wreck. It could be much worse, but it's no picnic.

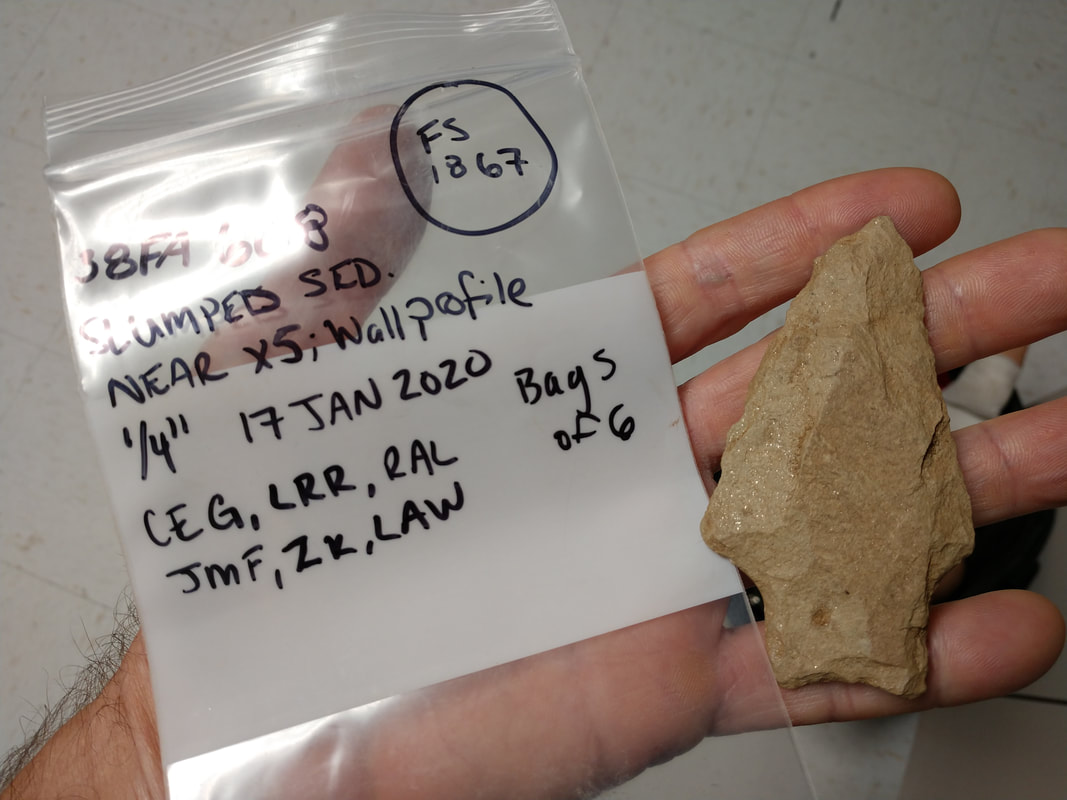

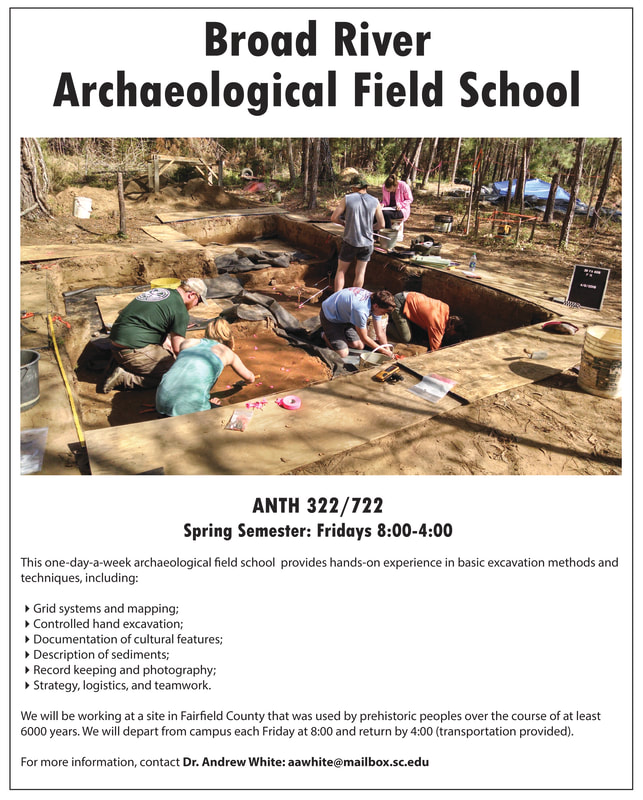

With the sudden stoppage of the field school, getting the work there to some kind of conclusion has fallen completely on me. Field archaeology is usually a team sport. So far, I've spent three days at the site on my own working on Unit 14. Next I'll tackle finishing the levels in the block. And then I'll be left to backfill. I'm not sure when I'll be able to pull all the equipment out (that's the least of my concerns right now). I've been making videos of my solo work at 38FA608 both as public outreach and to use as tools as I continue to try to teach my students something about field archaeology without actually being together with them in the field. You can find all of the 2020 videos here. Here is the latest, where I go through the steps of excavating a probable feature:

During our spring break, I worked with Stacey Young and other SCIAA personnel to excavate several units in the "basement" portion of 38FA608. That work was funded by an internal grant program. The goal was to explore the deeply-buried deposits at the site, hoping to positively identify an Early Archaic component. We got the fieldwork wrapped up just as things started to hit the fan. I'll make a video of the work and write more about it when I get the chance.

At the beginning of all this, I thought I'd be able to settle into a moderately productive routine at some point and be able to start getting ahead rather than just treading water. I'm an optimist, and I think that maybe that's still possible. It certainly hasn't happened yet, however. If I can get to the end of the day with the family and the house somewhat functional and feeling like I haven't fallen so far behind that I'll never be able to catch up, that's a win. A little bit of bad TV and/or drawing a picture at the end of the day are what passes for recreation.

I'll keep you posted as I finish up work at 38FA608. I'm hoping to find a way to provide a live feed on backfill day, which should be epic. I could really use some company out there, even if it's to jeer while I sweat my ass off. Stay tuned!

RSS Feed

RSS Feed