Unfortunately, I was not able to publish the paper open access so it will be behind a paywall for most people who read this. The first 50 people that read this can click this link and get access to the paper. If you're too late and you'd like a copy feel free to email me at [email protected] and I can send you a pdf.

|

I've had two new papers published this fall. The first, a critique of the evidence for Early Holocene caribou hunting on the submerged Alpena-Amberly Ridge in Lake Huron, came out in PaleoAmerica in October. Here is the abstract: A series of papers has developed the claim that stone features on the submerged Alpena-Amberley Ridge (AAR) in Lake Huron provides unique insight into the Paleoindian caribou-hunting economies of the Great Lakes. The documented human occupation of the AAR dates to the late Early Holocene (about 9000 calendar years ago): however, a time when glacial ice was far to the north and the region was occupied by hunting-gathering societies with ties to the western Great Plains and the deciduous forests of the Eastern Woodlands. Key elements of the caribou-hunting scenario as presented are poorly explained, contradictory, and/or ecologically unsound. Ethnographic and archaeological data demonstrate the use of structures for hunting other kinds of large game, presenting possibilities for alternative explanations. Constructing a satisfying explanation of the AAR features will require expanding the scope of investigation to develop and test multiple hypotheses that engage with the terrestrial archaeological record. The short version of the paper is that the case as it has been presented so far is not very strong. I see significant gaps in logic, data, and interpretation and remain unconvinced despite assertions that the skepticism about their interpretations is "long resolved" (that's a quote from the reply to my paper). Anyway, until the criticisms are substantively addressed I'm from Missouri on this one.

Unfortunately, I was not able to publish the paper open access so it will be behind a paywall for most people who read this. The first 50 people that read this can click this link and get access to the paper. If you're too late and you'd like a copy feel free to email me at [email protected] and I can send you a pdf. I spend all day yesterday at SEAC (Jackson, Mississippi) in the Paleoindian symposium organized by Scott Jones. There were lots of interesting papers -- among the best parts of these kinds of gatherings is being able to sit in a room and watch person after person talk about what they've been doing, what they've learned, what they think is important or interesting, etc. It's not necessarily the best way to get command of all the minutia of the work we do, but it is the best way to get a feel for what's going on across multiple regions, what people in different research programs have been working on, etc. One of the interesting aspects of a symposium like this is that you can see patterns of interest emerge -- different people working on different parts of the same problems in different regions. As the discussant for the session, Joe Gingerich organized his thoughts on the papers along three main lines: landscape, technology, and issues of society. These articulate with one another in all kinds of interesting ways. The papers in the session as well as the "after session" discussions I had at the bar and at dinner made me optimistic that maybe we really are heading into an era where we can have some substantive discussions about Paleoindian societies that make innovative use of all the new data that have been gathered over the last few decades. Anyway, I think my paper went well. I basically set out to ask if/how we can gain some traction on understanding how Paleoindian societies were organized internally in terms of their constituent "building block" parts: families, foraging groups, maximal bands, etc. This is a question where multiple lines of evidence can be brought to bear. That doesn't mean, however, that it's easy to answer. I think we have enough in front of us now from across the Eastern Woodlands, however, that we can take a hard look at it and try to move the ball forward. Here is a pdf of my presentation. I also put it in on my Academia page. Also, for the record: as far as I can recall, the Jackson, MS, airport is the only airport I have ever been in where the coffee shop also sells cold bottles of beer.

It has been a busy few weeks. As usual, I have more topics than time. At this point, I'm going to just accept that my blog sometimes functions as an open access journal. Here is the bullet point version of what I've been up to. We'll do art first, then archaeology.

The Jasper Artist of the Year Is . . . Not Me As I wrote in December, I was one of three finalists nominated for Jasper Artist of the Year (in the visual arts category). The awards ceremony was last Friday. I did not win the award: that honor went to Trahern Cook. I met some new people, drank some wine, and had a good time (the picture above was taken there). Congratulations to all the winners! New Pieces Over the Holidays In addition to "Desire," I completed several other smallish pieces over the holiday break.

Fact Bucket Videos: Six Down, One to Go I'm still working to finish up editing the student videos from my Forbidden Archaeology class last semester. I finished one on Atlantis last week and one on pyramids today. You can find them on my YouTube channel, along with videos about my archaeological fieldwork and my art. New Grant For Collections Work I'm happy to announce that I have received grant monies from the Archaeological Research Trust to continue inventorying and preliminary analysis of chipped stone projectile points from the Larry Strong Collection. You may remember me writing about working with the Early Archaic materials a while ago. I'm still working with those (more on that later), but now I'm going to move on in time and process the Middle and Late Archaic stuff. Part of the rationale is that I'll be dealing with those time periods in the materials we've been excavated at the field school. South Carolina Archaeology Class: We're Making a Movie I'm teaching South Carolina Archaeology (ANTH 321) this semester. The class is bigger than in years past. That's good from an enrollment standpoint, but a challenge from a teaching standpoint. In the spirit of experimentation, I decided to build in a class video project. We'll be making a video attempting to showcase the archaeology of this state. I've divided the students up into groups and given them topics (mostly organized chronologically) that they're responsible for. They're going to research their topics and develop proposals about what issues, artifacts, sites, and people should be included the video. Then we'll take it from there. Go Deep! Today I submitted a grant proposal for systematic exploratory work on the deep deposits at 38FA608 (the field school site). We know now several things about the sediments below the Middle Archaic zones: (1) they're deep; (2) they're Late Pleistocene/Early Holocene in age; and (3) they contain artifacts. I don't believe I've mentioned it publicly, but I submitted a sample for OSL data from the deepest stratum we've documented so far (about 5m below the original surface) and it returned a result around the Last Glacial Maximum. Also, we've found an Early Archaic Kirk point in a disturbed part of the site. What all that means is that the landform did indeed exist at the end of the last Ice Age and (minimally) Early Archaic peoples were using it. In other words, there's a really good potential for some very high integrity buried archaeology there. Fingers crossed. Other News

In other news . . . our 2003 4Runner finally suffered a terminal injury. And I'm tearing out our rotted deck. And I've started working a rabbit sculpture that's big enough to sit on. It will have a tractor seat. And a gear shift. And a dashboard. And now you are up to date. The Earth on Fire? A Few Thoughts on the Claim of Widespread Burning at the End of the Last Ice Age2/6/2018

My house is still a sick ward, so I think the best contribution I can make to archaeological science today is to type out a few thoughts about a pair of papers that came out last week. The papers ("Extraordinary Biomass-Burning Episode and Impact Winter Triggered by the Younger Dryas Cosmic Impact ∼12,800 Years Ago," parts 1 and 2) lay out evidence for an anomalous episode of widespread burning that coincided with the onset of the Younger Dryas. The papers are unfortunately behind a Journal of Geology paywall. As you might expect from the mental image that the title conjures, the papers have gotten a lot of play in the media. I'm going to play the sensationalism card with this image: These papers are complicated, synthesizing a lot of data and information. I count 27 authors, including my South Carolina colleague Christopher Moore. There is a lot to digest here. I'll leave it to others to evaluate the parts of the papers that are outside my area of expertise. What I'm most interested in how the claims of widespread burning mesh with the Late Pleistocene archaeological record of eastern North America. But first, what do the papers say? In the first one ("Ice Cores and Glaciers") the authors present data suggesting anomalous peaks in "combustion aerosols" in ice cores layers from several continents dating to about 12,800 years ago. Those concentrations, presumably caused by combustion of organic matter, coincide with anomalous concentrations of dust and platinum which the authors associate with a cosmic impact. This is a good summary of the scenario that they envision: "The best explanation for the available evidence is that Earth collided with a fragmented comet. If so, aerial detonations or ground impacts by numerous relatively small cometary fragments, widely dispersed across several continents, most likely ignited the widespread biomass burning observed at the YD [Younger Dryas] onset." For the uninitiated, the Younger Dryas was a temporary and rather sudden return to glacial conditions that occurred, for some reason, as the earth was coming out of its last glacial period. The causes of the Younger Dryas are a subject of debate, with the majority view being that the change was caused by an interruption in global ocean circulation patterns. These "Biomass-Burning" papers add to a growing body of scholarly work arguing for an alternative scenario, attributing sudden global cooling to a "nuclear winter" effect caused by atmospheric dust and smoke on a massive scale triggered by cosmic impacts.

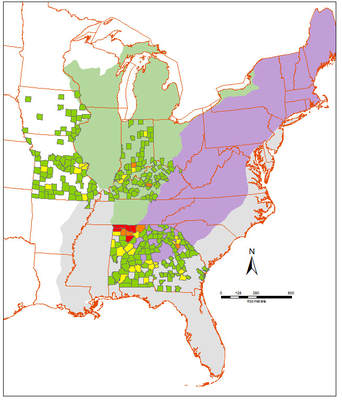

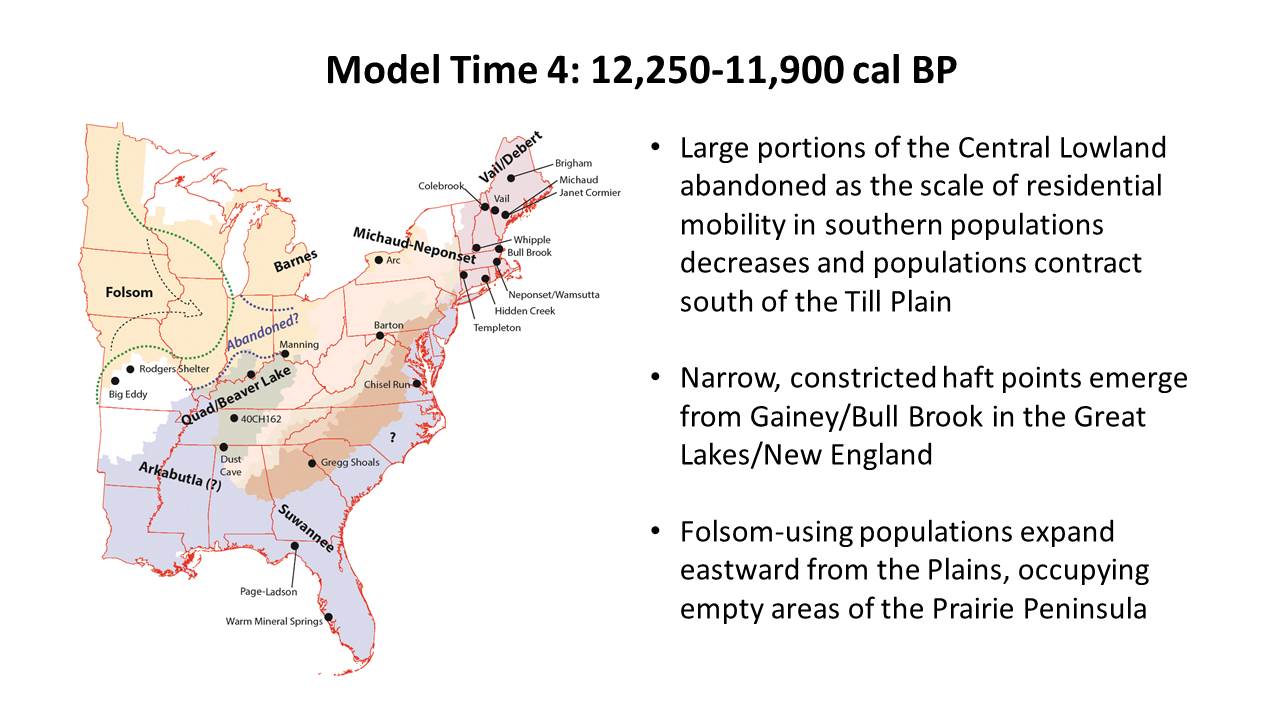

The second paper ("Lake, Marine, and Terrestrial Sediments") examines dated sediment cores from numerous locations for the presence of peaks in charcoal and soot that would have been deposited as impact-related wildfires burned at large scales. Based on that analysis, the authors conclude that about 9% of the Earth's biomass was burned at the Younger Dryas boundary. Nine percent is a big number no matter how you slice it. That's a lot of stuff on fire. I'll leave it to the climate people to evaluate how that number translates into changes in global weather patterns and weather that could have been a trigger for the Younger Dryas. We know the Younger Dryas happened, and we know that human societies would have had to have adjusted to it. As an archaeologist who works in the Late Pleistocene and Early Holocene, I immediately wonder how such a "biomass burning" scenario articulates with the archaeological record. The burning would had to have been spotty (nine percent is not, after all, 100%). Even though the smoke and soot from combustion in the atmosphere is supposed to have contributed to the "nuclear winter" effect, however, direct evidence for it doesn't show up in every core. There are several possible reasons for those absences, including post-depositional processes ("the soot was deposited but has been destroyed"). What intrigues me is the possibility that some of variability in the deposition of charcoal/soot could be linked to which areas were actually burned. Surely the wildfires would have been of varying scale and duration, and would have affected nearby environments in complex ways. We're talking about global climate change, but local/regional burning (which presumably would have taken place over a relatively short period of time). Creating some kind of geographic map of which areas were ostensibly burned would be useful for comparison to what we know/suspect about shifts in human population in response to the Younger Dryas. I feel the "cosmic collision apocalypse" trope has been seriously abused, mostly by those outside of the actual scholarly debate. If there was an impact that triggered the Younger Dryas, it did not result in the extinction of human populations in eastern North America in any way that I can see. What I see instead is change in the distribution of populations and shifts in technology, subsistence, and mobility. Clovis doesn't "go extinct:" it changes into something else that actually looks a lot like Clovis (large, fluted, parallel-sided points similar to Clovis [e.g., Gainey/Bull Brook, Redstone] are the technological descendants of Clovis and post-date the Younger Dryas boundary). Large-scale time/space changes in the distribution of Paleoindian populations are something I've been interested in. So far, I haven't seen anything that looks to me to be a direct response to some kind of cataclysm. But what would such a response look like and how we tell it apart from the alternatives? These are good questions to ask and not simple ones to answer. I am unconvinced that there is good evidence for some kind of significant, widespread post-Clovis population drop. In some areas of the east (i.e., the Northeast and the lower peninsula of Michigan), human populations actually seem to expand their range northward as the climate gets colder. Long story short: it's complicated. We surely have the tools to investigate human responses to the larger patterns of climate change that characterize the Younger Dryas. I do not know, however, if the terrestrial sediment record, as it exists now or as it can be analyzed in the future, is fine-grained enough to develop a model of where in Eastern Woodlands large-scale burning would have occurred in the "nuclear winter" scenario. Likewise, it's not clear that the archaeological record is sufficiently fine-grained to track the short term responses of human populations to the new landscape that would have been created by widespread burning. That's all I've got for now. Fingers crossed a comet doesn't hit us before we get all this figured out. Today is my last morning in Tulsa at SEAC 2017. I spent all day yesterday in the "Paleoindian and Early Archaic Southeast" symposium: 18 papers that included state-by-state updates of what we know and the data we have and treatments of topics such as megafauna in the Southeast, plant use by early foragers in the region, wet site archaeology in Florida, lithic technologies, etc. It was a marathon.

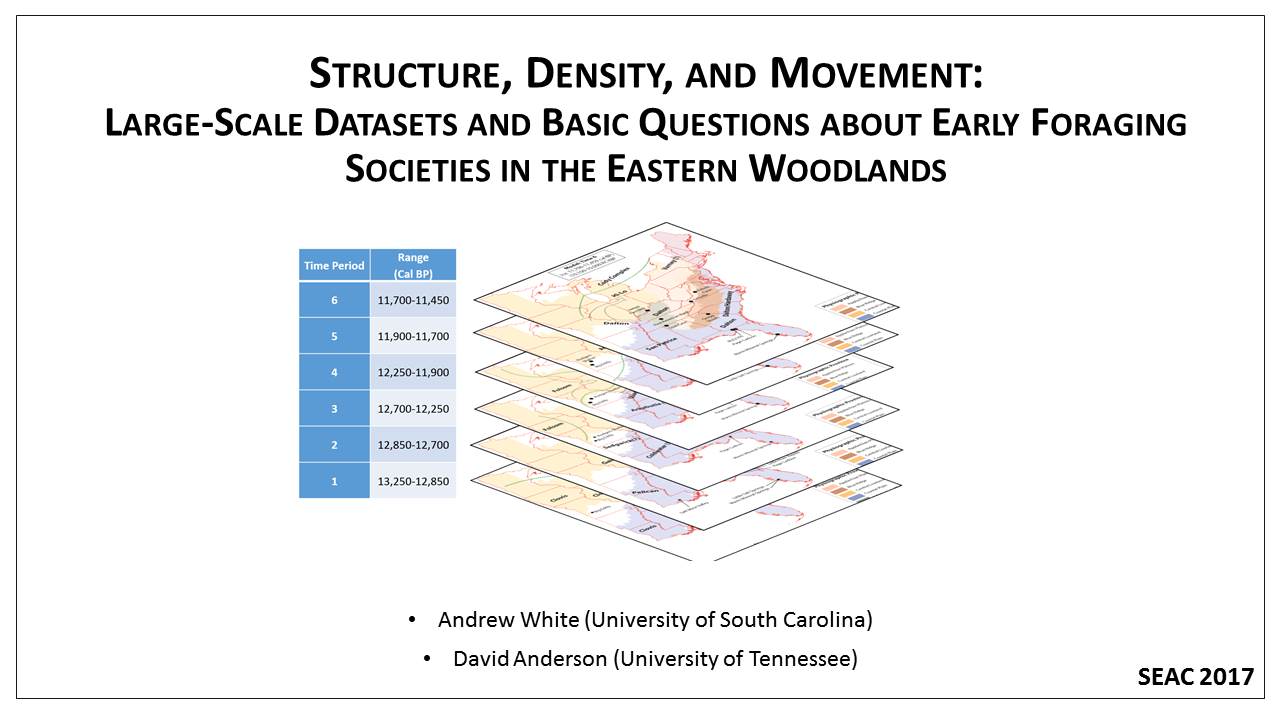

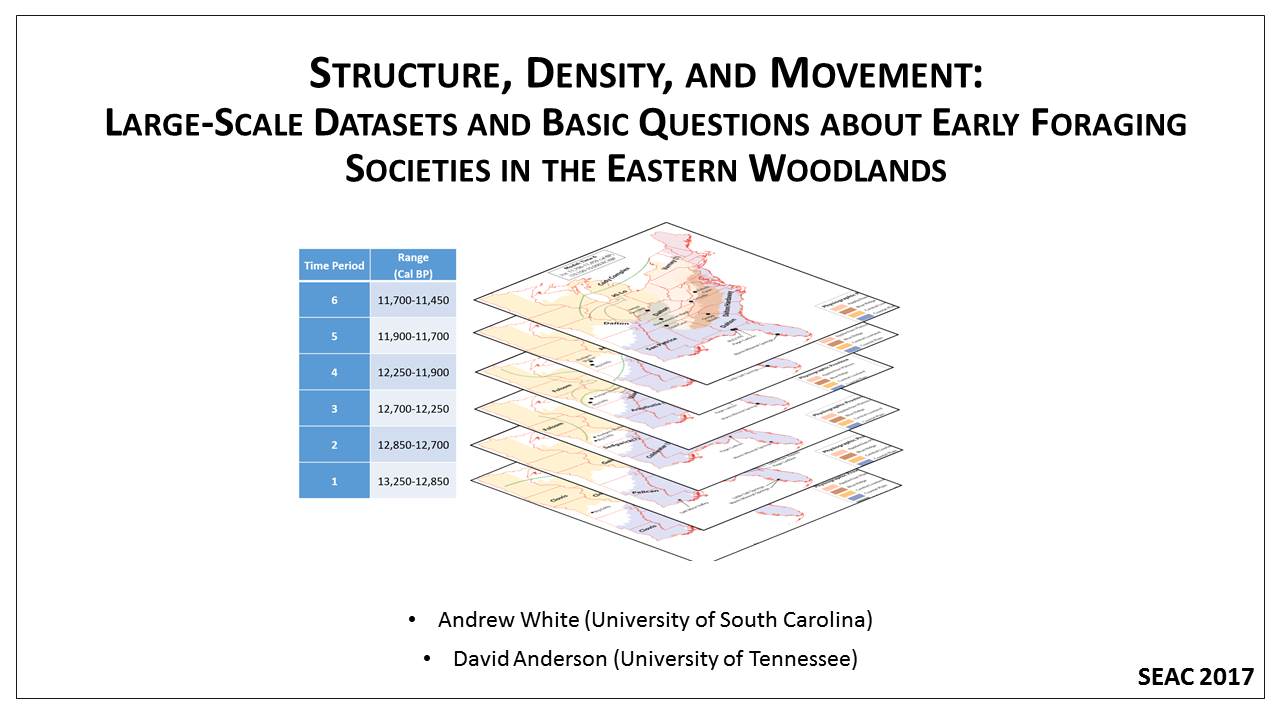

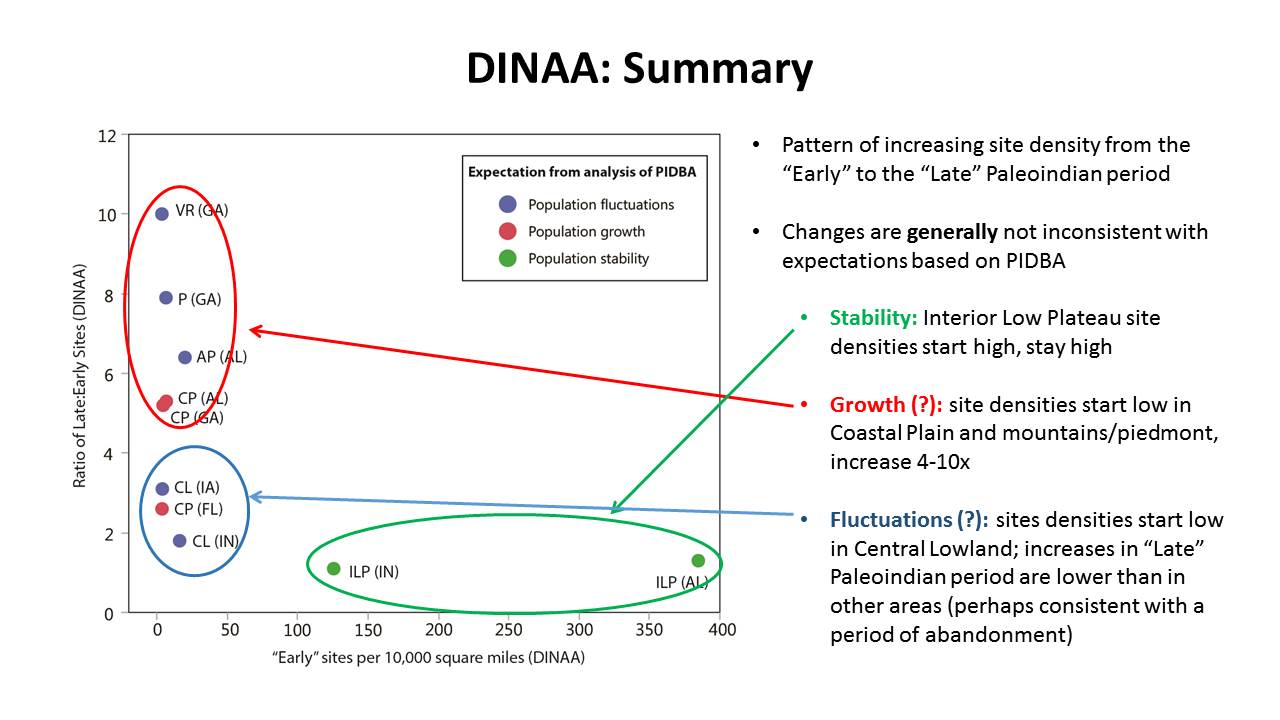

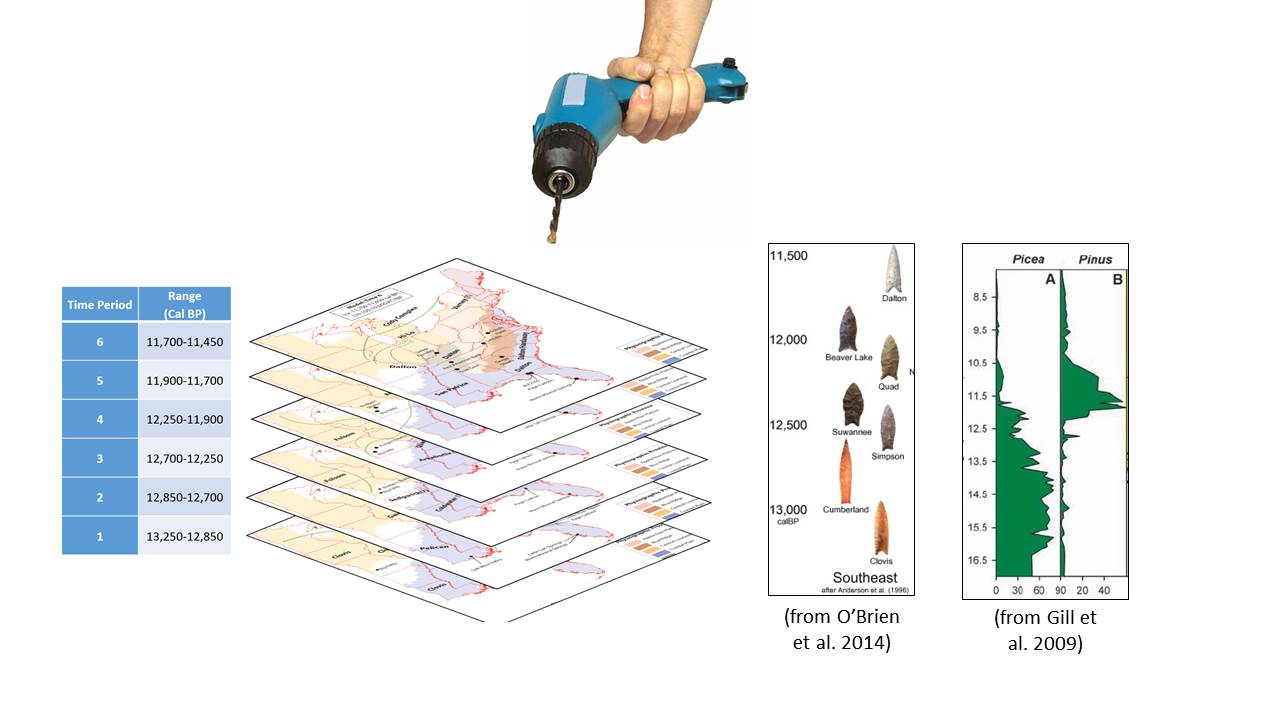

My presentation with David Anderson was last in the lineup. I was tasked with an effort at a "big picture" demography paper. It was a lot to talk about in a short time (20 minutes) -- a difficult balancing act to discuss the dense data from such a large area and be able to explain how I tried to integrate it all into a geographical/chronological model that can be evaluated on a region-by-region basis. Anyway . . . the detail will be there in the publications that result from the endeavor. I uploaded a pdf of my presentation here. Some of the details will change as we work through the process of refining the analysis and dividing the content into multiple papers. But you should be able to get a decent idea of what we were going for. I'm currently in Tulsa, OK, at the 2017 Southeastern Archaeological Conference. I took a break this afternoon from papers and talking to hole up in my hotel room and put the finishing touches on the presentation I'll be giving tomorrow. I'm honored to be senior author on a paper with David Anderson (University of Tennessee). Our paper will be last tomorrow in a marathon symposium organized by Shane Miller (Mississippi State University), Ashley Smallwood (University of West Georgia), and Jesse Tune (Fort Lewis College).

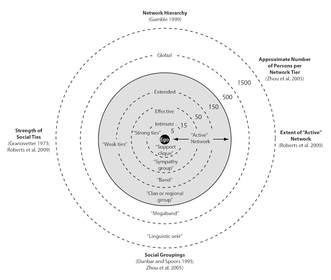

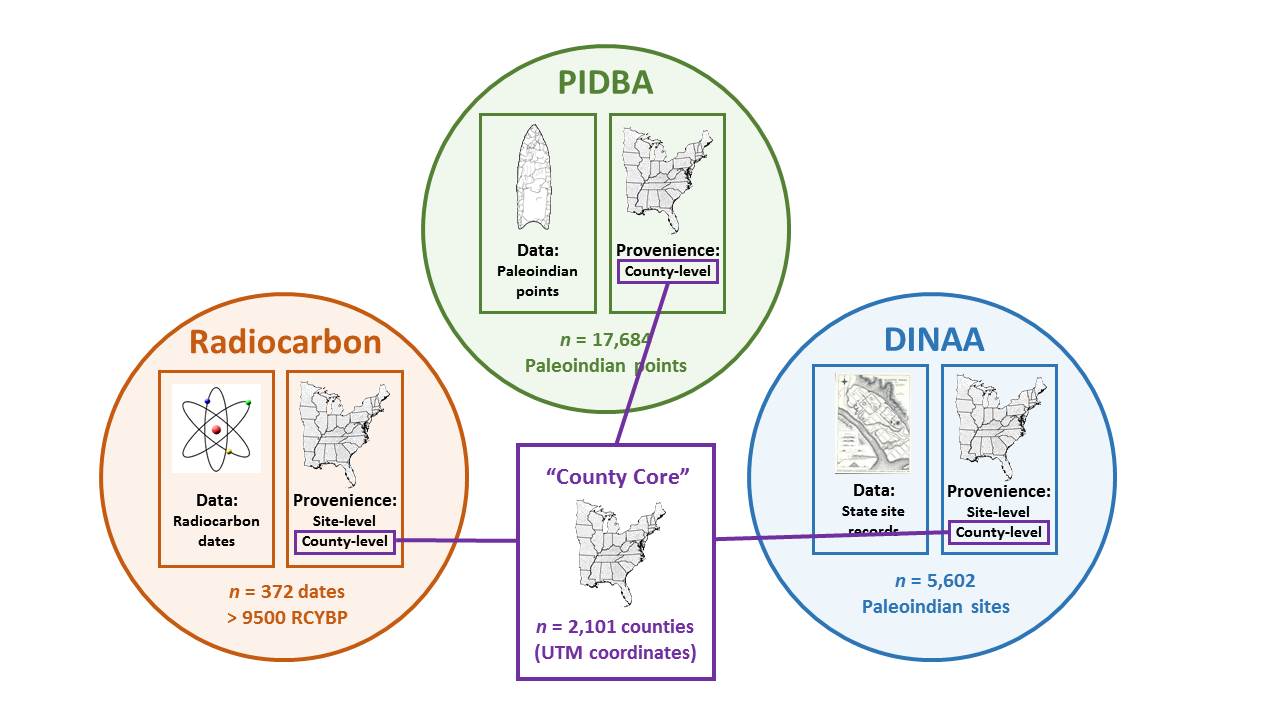

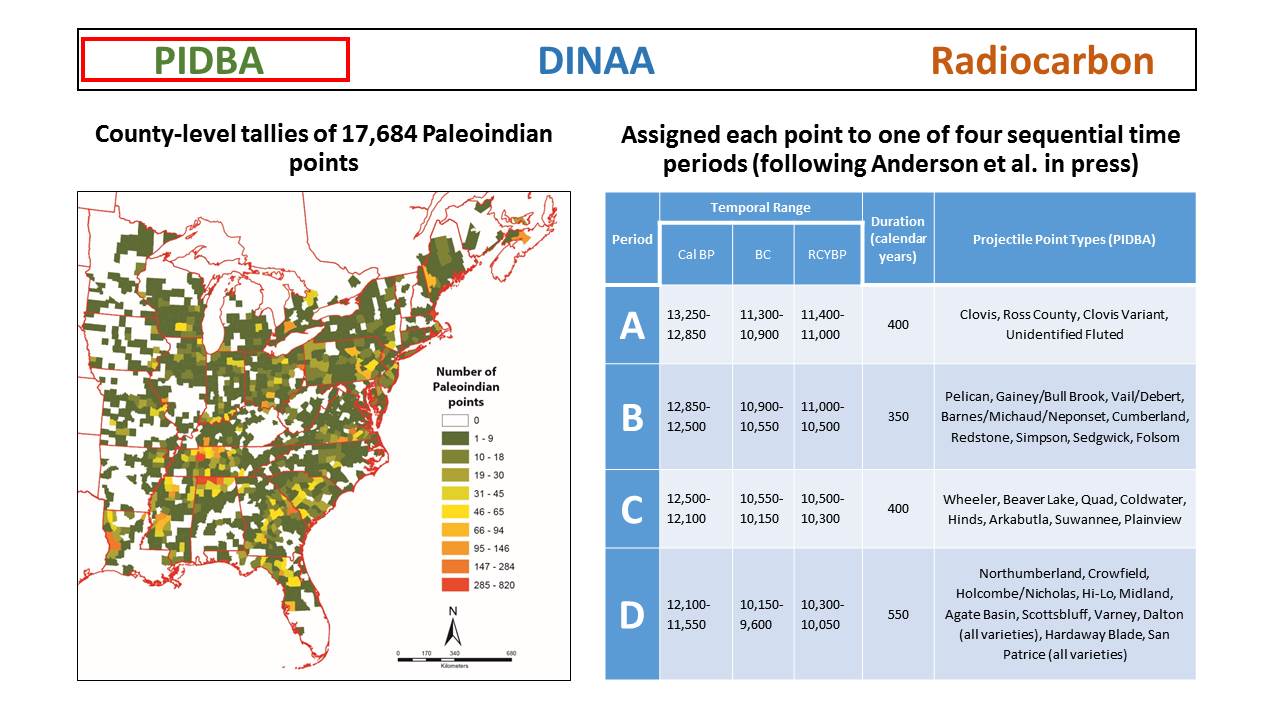

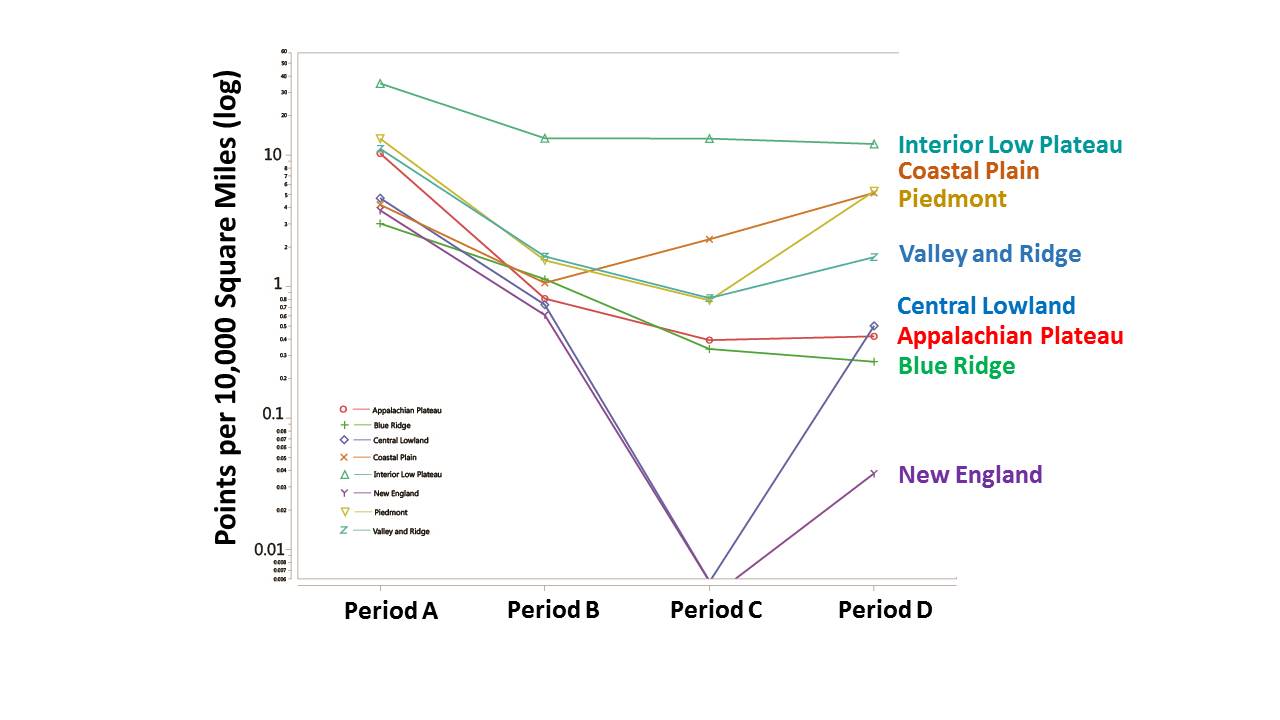

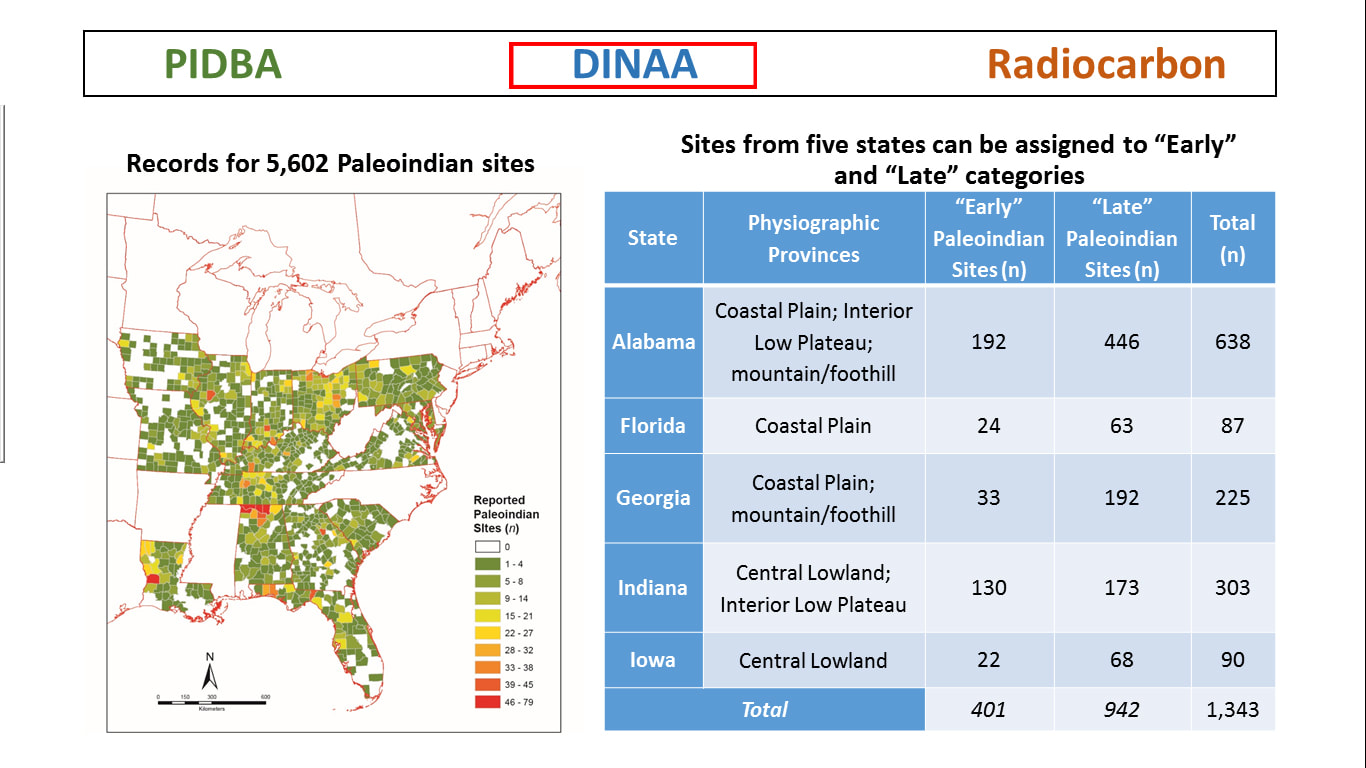

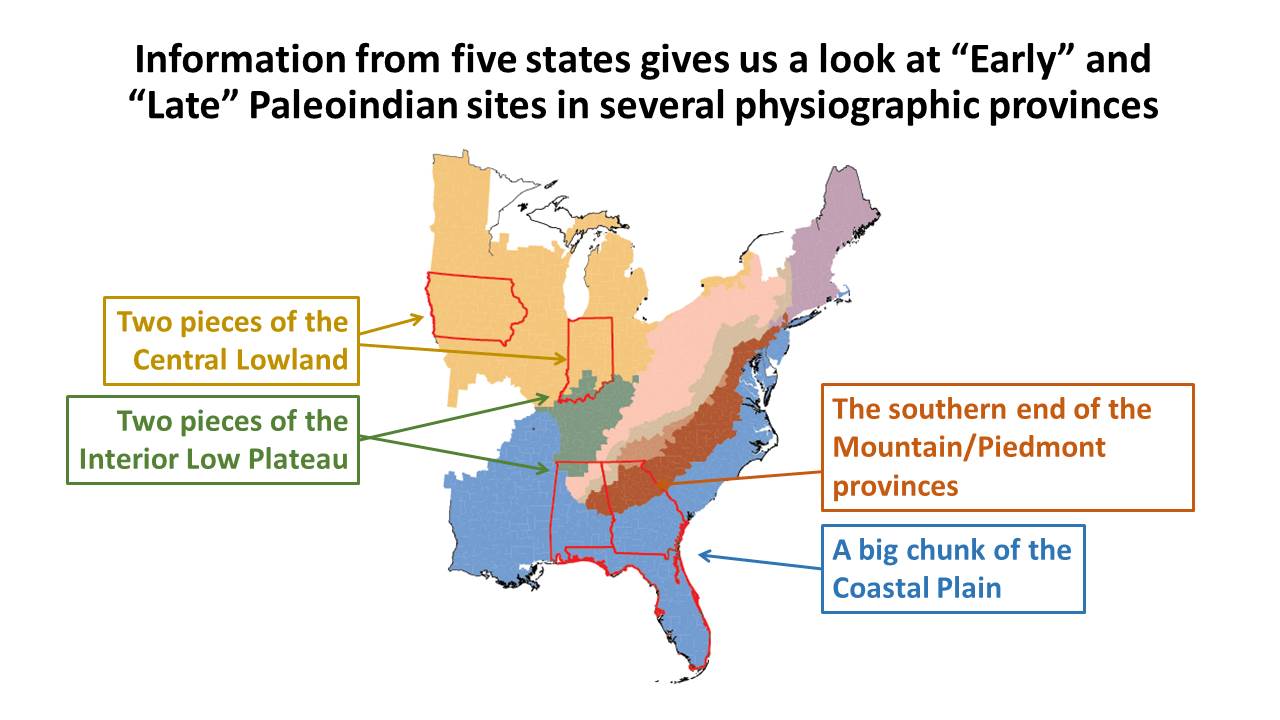

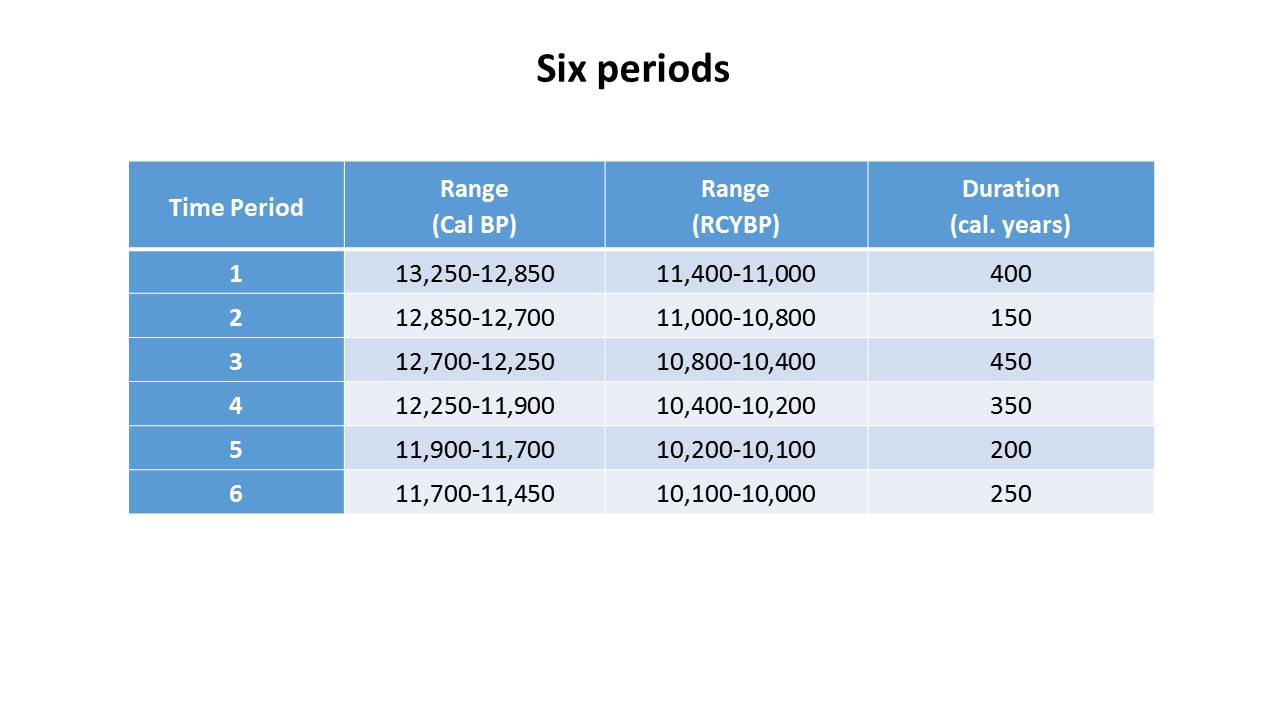

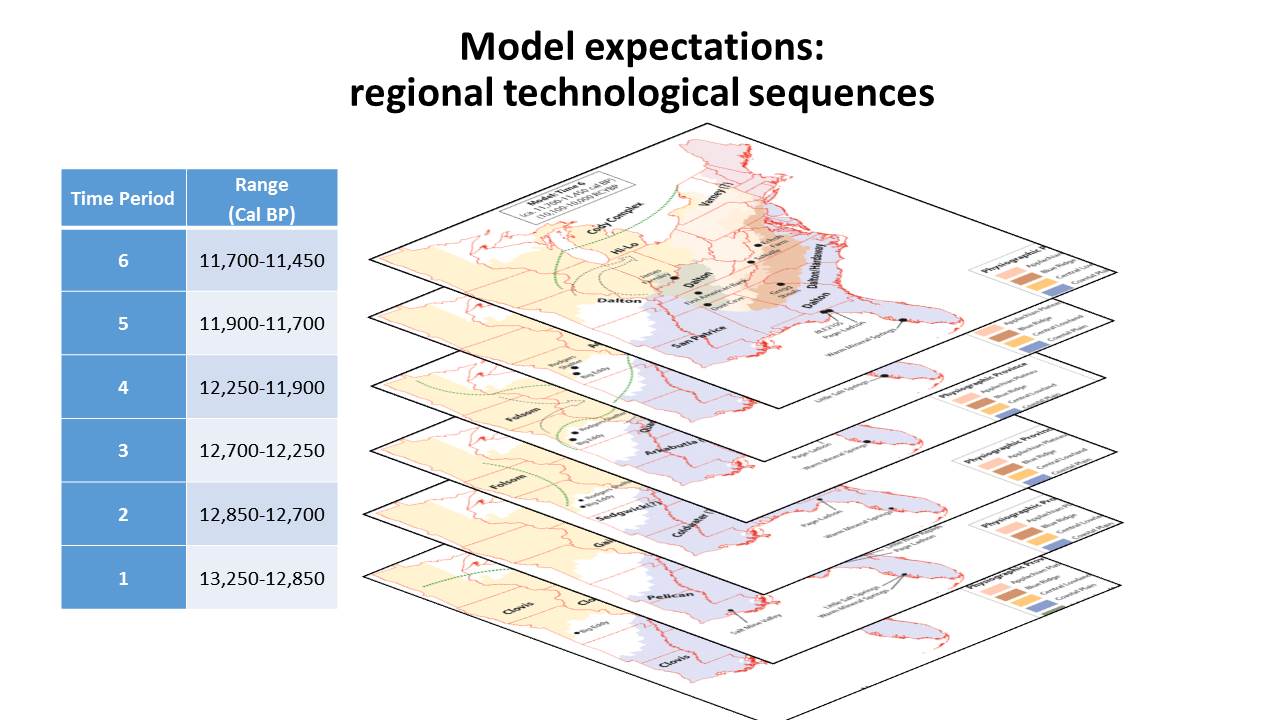

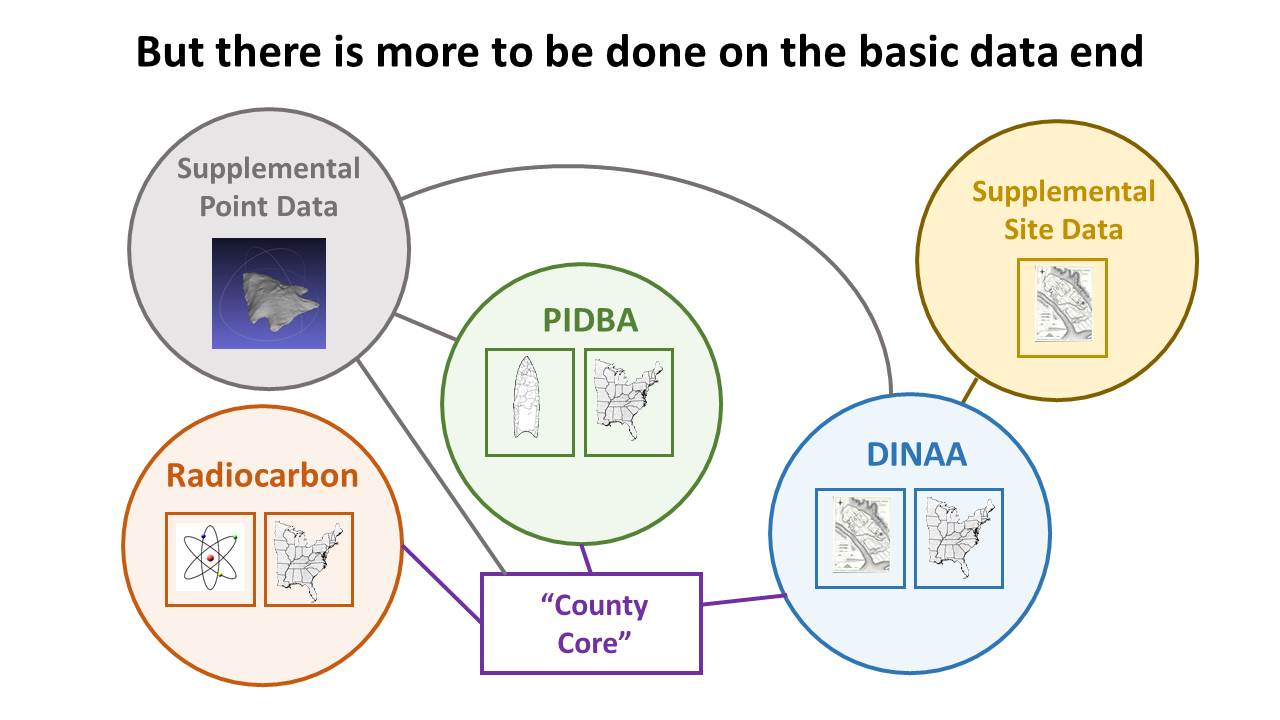

I'm really looking forward to the session, which will present summaries, updates, and syntheses of work from across the Southeast. It's intended to be a 20-year update to the work that culminated in the landmark Paleoindian and Early Archaic Southeast volume that was published in 1996. Congratulations are due to the organizers who conceived of the symposium and pulled it off. I briefly discussed our paper back in September. Significant work has happened since then, and I'm pretty happy with the result. The point of doing a "big" paper like this, in my view, is to attempt to identify and describe patterns that require explanation. We used information from three large datasets -- PIDBA, DINAA, and an always "in progress" compilation of radiocarbon dates -- to investigate patterns of population stability/fluctuation during the Paleoindian period in the Eastern Woodlands. As of now (rushing through this blog post so I can go out to dinner) I like the result: a six period chronological/geographical model identifying the time/space parameters of population stabilities and fluctuations. As I listen tomorrow to region-by-region updates on what we know about the Paleoindian period in the Southeast, I will almost certainly learn of many things that are wrong. But I will be listening to the results of others' work with a model in mind. That's useful. As the famous quote goes: "all models are wrong, but some are useful." To me, a useful model is a machine for thinking that makes predictions about the world that can be evaluated. So I'm looking forward to seeing what I got wrong. I wish I had a big piece of paper I could spread out on a table so I could take notes time period by time period, region by region. After this updated photograph of Woody Guthrie, I'll post images of a few key slides from the presentation. I'll put the whole thing on my Academia page tomorrow after the dust settles. [Update 11/13/2017: the presentation is available here.] The blog has been on the back burner while I deal with the beginning-of-the-semester crunch. I've got a lot going on this year, so I'll probably have less time to write than I did in years past. Keeping all the parts of my three-headed monster of a research agenda moving is more than a full time job. I wanted to write a quick post about the presentations I've committed to for the fall (SEAC) and spring (SAA) conferences, as they give you a pretty good idea on what's going on with some of my "big picture" work. I gave a presentation about my work on understanding the Kirk Horizon to the Augusta Archaeological Society at the end of August, and I'll be giving an informal presentation to SCIAA next week synthesizing what we know so far about the natural/cultural deposits at 38FA608 (site of last spring's Broad River Archaeological Field School). Here's what I'll be doing at the regional and national conferences:  SEAC (November 2017, Tulsa, OK) David Anderson and I are teaming up to give a paper titled "Structure, Density, and Movement: Large-Scale Datasets and Basic Questions about Early Foraging Societies in the Eastern Woodlands." The paper will part of a symposium organized by Shane Miller, Ashley Smallwood, and Jesse Tune titled The Paleoindian and Early Archaic Southeast: The Last 20 Years, 1996-2016. Here is the abstract of our paper: "Distributions of diagnostic projectile points show that the Paleoindian and Early Archaic societies of the Eastern Woodlands were spatially-extensive, occupying vast and varied landscapes stretching from the Great Lakes to the Florida Peninsula. The scales of these societies present analytical challenges to understanding both (1) their organization and (2) how and why the densities and distributions of population changed during the Late Pleistocene and Early Holocene. We integrate several large datasets – point distributions, site locations, and radiocarbon dates – to address basic questions about the structure and demography of the Paleoindian and Early Archaic societies of the Eastern Woodlands." We'll be integrating data from PIDBA, DINAA, and my ongoing radiocarbon compilation. There will be some significant work involved in meshing all this stuff together in a GIS framework that we can use analytically, so that will be one of the main things on fire for me in the coming month.  SAA Meeting (April 2018, Washington, D.C.) At this year's SAA meetings, I'll be contributing to Scott Jones' symposium titled Forager Lifeways at the Pleistocene-Holocene Transition. My paper is titled "Patterns of Artifact Variability and Changes in the Social Networks of Paleoindian and Early Archaic Hunter-Gatherers in the Eastern Woodlands: A Critical Appraisal and Call for a Reboot." Here is the abstract: "Inferences about the social networks of Paleoindian and Early Archaic hunter-gatherer societies in the Eastern Woodlands are generally underlain by the assumption that there are simple, logical relationships between (1) patterns of social interaction within and between those societies and (2) patterns of variability in their material culture. Formalized bifacial projectile points are certainly the residues of systems of social interaction, and therefore have the potential to tell us something about social networks. The idea that relationships between artifact variability and social networks are simple, however, can be challenged on both theoretical and empirical grounds: complex systems science and ethnographic data strongly suggest that patterns of person-level interaction do not directly correspond to patterns of material culture visible at archaeological scales. A model-based approach can be used to better understand how changes in human-level behaviors “map up” to changes in both the system-level characteristics of social networks and the patterns of artifact variable that we can describe using archaeological data. Such an approach will allow us to more confidently interpret changes in patterns of artifact variability in terms of changes in the characteristics and spatial continuity/discontinuity of social networks during the Pleistocene-Holocene transition in the Eastern Woodlands." This is a basket of questions that was the main focus of my dissertation work. My goal is to lay out the case for why we really need to be doing things differently than we are in order to get at questions about social networks and social interaction. With the SAA meetings still months away, I plan to do new modeling work to support my argument. If I'm to do that, I'll have to ramp up my modeling efforts and deal with some issues around adding space back into the main models I've been working with. It needs to be done, so committing to a paper is a way to make sure I prioritize it. I'll also be participating in a "Lightning Round" about engaging pseudoarchaeology. In this session (organized by Khori Newlander), the participants will each get just three minutes. No abstract is required for this one. As of now, I plan to use my time for "Swordgate: How to Win Friends and Influence People."

It's the end-of-semester crunch for many of us in the academic world. My Facebook feed is filled with posts by people who been grading for too long and finding too many cases of student plagiarism. The end of my road was easy this semester, as I taught a very pleasant field school populated by a good group of students. Having taught a 4/4 one year, I feel for all of you still slogging away.

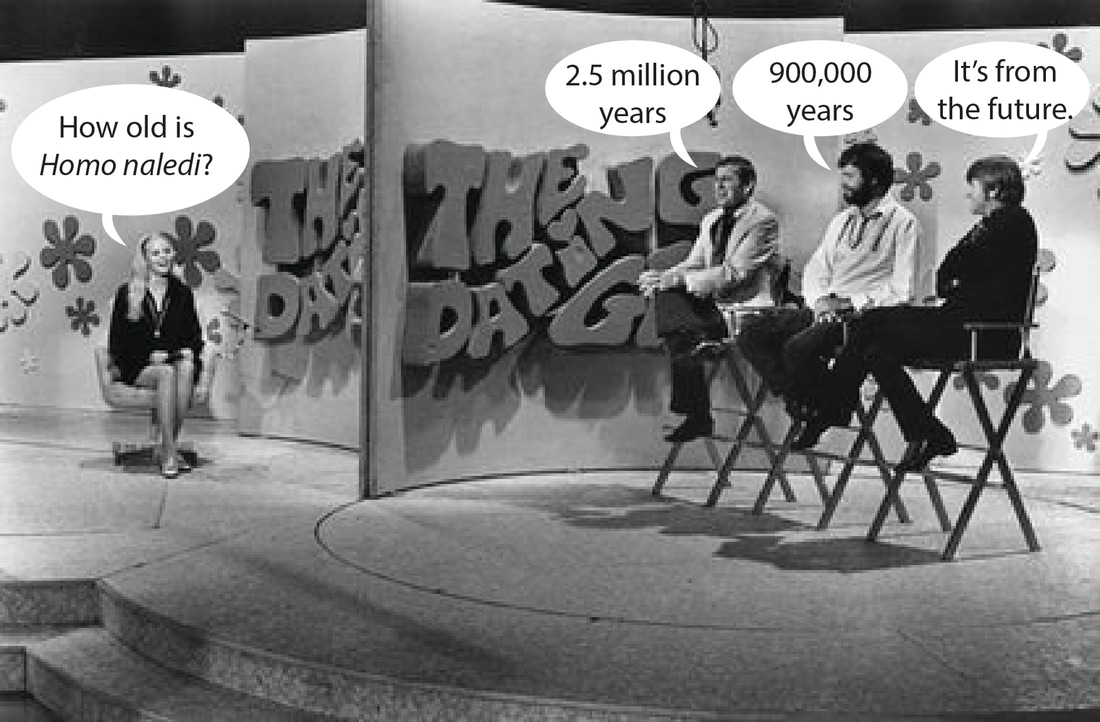

I wanted to take a minute to write about two stories related to claims for sites of Middle Pleistocene age in two different corners of the world. Unless you're grading papers in a lead-lined underground bunker, you heard about the claim for a 130,000-year-old archaeological site in California that was published in Nature yesterday. That's the first one. The second one involves an age estimate of 250,000 for the Homo naledi remains first described in September of 2015. The first claim is buzz-worthy because of its extreme earliness (a good 115,000 years prior to what most archaeologists accept as good evidence for human entry into the Americas). The second claim is surprising for its lateness. Let's do the second one first. Homo naledi is Only 250,000 Years Old? The announcement of Homo naledi and the results of the Rising Star Expedition made a huge splash in the fall of 2015 (I gave my take on it here). One of the main unresolved issues at the time of the initial announcement was that the remains were not dated. The lack of an age estimate made it difficult to frame the analysis in terms of evolutionary relationships with other hominins and the implications of the claims that Homo naledi was burying its dead. If the remains are very early (say, close to 2 million years old . . . ), the claims for organized mortuary behavior are spectacular. If they're very late, the mosaic of primitive and derived features becomes very curious. Two days ago, the New Scientist ran a story titled "Homo naledi is Only 250,000 Years Old -- Here's Why that Matters." Here is a quote from that piece: "Today, news broke that Berger’s team has finally found a way to date the fossils. In an interview published by National Geographic magazine, Berger revealed that the H. naledi fossils are between 300,000 and 200,000 years old. “This is astonishingly young for a species that still displays primitive characteristics found in fossils about 2 million years old, such as the small brain size, curved fingers, and form of the shoulder, trunk and hip joint,” says Chris Stringer at the Natural History Museum in London."

If you click on the link to the interview in National Geographic, you'll find that it leads to a photograph of a magazine page posted on Twitter by Colin Wren. I'm unable to access the original piece in National Geographic. I'm not quite sure what is going on, but presumably a formal publication explaining the age estimate is in the works and will be out soon.

A 250,000 year age would, indeed, be surprising. Previous age estimates have ranged widely, from 900,000 years old (based on dental and cranial metrics) to 2.5 to 2.8 million years old (based on overall anatomy). Age estimates based on the anatomical characteristics of the remains are problematic, obviously, as they rely on assumptions about the pattern, direction, and pace of evolutionary change that may not be correct. Hopefully the latest age estimates are independent of the anatomy (i.e., have a geological basis). This blog has some additional background.

And now on to the second one, which concerns . . .

A Middle Pleistocene Occupation of North America? It's hard to know where to even start with this one. The claim is bold, the journal is prestigious, the popular press has been all over it, and the reaction from professionals has been swift and (as far as I can tell) overwhelmingly negative. The reactions I have seen among my colleagues and friends have been almost universally skeptical, ranging from amusement to mild outrage. I'll just summarize all that with gif I saw in an online discussion about the paper:

The claim centers around an assemblage of stones and mastodon bones that the authors interpret as unequivocal evidence of human activity in California at the Middle/Late Pleistocene transition (ca. 130,000 years ago). Here is the first part of the abstract of the Nature paper by Steven Holen and colleagues:

"The earliest dispersal of humans into North America is a contentious subject, and proposed early sites are required to meet the following criteria for acceptance: (1) archaeological evidence is found in a clearly defined and undisturbed geologic context; (2) age is determined by reliable radiometric dating; (3) multiple lines of evidence from interdisciplinary studies provide consistent results; and (4) unquestionable artefacts are found in primary context. Here we describe the Cerutti Mastodon (CM) site, an archaeological site from the early late Pleistocene epoch, where in situ hammerstones and stone anvils occur in spatio-temporal association with fragmentary remains of a single mastodon (Mammut americanum). The CM site contains spiral-fractured bone and molar fragments, indicating that breakage occured while fresh. Several of these fragments also preserve evidence of percussion. The occurrence and distribution of bone, molar and stone refits suggest that breakage occurred at the site of burial. Five large cobbles (hammerstones and anvils) in the CM bone bed display use-wear and impact marks, and are hydraulically anomalous relative to the low-energy context of the enclosing sandy silt stratum. 230Th/U radiometric analysis of multiple bone specimens using diffusion–adsorption–decay dating models indicates a burial date of 130.7 ± 9.4 thousand years ago. These findings confirm the presence of an unidentified species of Homo at the CM site during the last interglacial period (MIS 5e; early late Pleistocene), indicating that humans with manual dexterity and the experiential knowledge to use hammerstones and anvils processed mastodon limb bones for marrow extraction and/or raw material for tool production."

The 130,000 year-old date is way, way, way out there in terms of the accepted timeline for humans in the Americas. Does that mean the conclusions of the study are wrong? Of course not. And, honestly, I don't even necessarily subscribe to the often-invoked axiom that "extraordinary claims require extraordinary evidence." I think ordinary, sound evidence works just fine most of the time when you're operating within a scientific framework. Small facts can kill mighty theories if you phrase your questions in the right way.

So how should we view claims like this one? For this claim to stand up, two main questions have to withstand scrutiny. First, is the material really that old? Second, is the material really evidence of human behavior? If we accept the age of the remains, we're left with the second question about whether those remains show convincing evidence of human behavior. As you can see from the abstract, the claim for human activity has several components (modification of the bones, the presence and locations of stone cobbles interpreted as tools, etc.). The authors contention (p. 480) is that

"Multiple bone and molar fragments, which show evidence of percussion, together with the presence of an impact notch, and attached and detached cone flakes support the hypothesis that human-induced hammerstone percussion was responsible for the observed breakage. Alternative hypotheses (carnivoran modification, trampling, weathering and fluvial processes) do not adequately explain the observed evidence (Supplementary Information 4). No Pleistocene carnivoran was capable of breaking fresh proboscidean femora at mid-shaft or producing the wide impact notch. The presence of attached and detached cone flakes is indicative of hammerstone percussion, not carnivoran gnawing (Supplementary Information 4). There is no other type of carnivoran bone modification at the CM site, and nor is there bone modification from trampling."

My impression is that most archaeologists are, like me, are skeptical that all other possible explanations for the stone and bone assemblage can be confidently rejected. I'm no expert on paleontology and taphonomy, but as I thought through the suggested scenario, I wondered how all the meat came off the bones before before the purported humans smashed them open with rocks. The authors state that there's no carnivore damage, and unless I missed it I didn't see any discussion of cutmarks left by butchering the carcass with stone tools. So where did the meat go? If it wasn't removed by animals (no carnivore marks) and wasn't removed by humans (no cutmarks) did it just rot away? If so, would the bones have still been "green" for humans to break them open?

The absence of cut marks would be perplexing, as we have direct evidence that hominins have been using using sharp stone tools to butcher animals since at least 3.4 million years ago. The 23,000-year-old human occupation of Bluefish Cave in the Yukon is supported by . . . cutmarks. We know that Neandertals and other Middle Pleistocene humans had sophisticated tool kits that were used to cut both animal and plant materials. Is it possible that pre-Clovis occupations in this continent extend far back into time? Yes, I think it is. Does this paper convince me that humans messed around with a mastodon carcass in California at the end of the Middle Pleistocene? No, it does not.

Some of my friends seem angry that the paper was published. I have mixed feelings. I'm not at all convinced by what I've read so far, but I think claims like this serve a useful purpose whether or not they turn out to be correct. I can understand the concerns I've heard voiced about unfairness in the standards of evidence and argument that are acceptable at various levels of publication, but I also think there should always be room for making bold claims about the past as long as those claims have some basis in material evidence that can be independently evaluated. It will be interesting to see how the buzz over this paper plays out. Will other professionals carefully examine the remains and offer up their opinions? Will the claim be quickly dismissed and forgotten about?

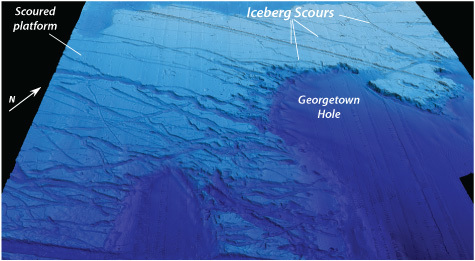

One thing I can guarantee is that the "fringe" will be on the Cerutti Mastodon like a wet diaper: they've already got a laundry list of "Neanderthal" remains from the New World (some buried in Woodland-age earthen mounds!) and "pre-Flood" sites into which they'll weave this report into. Maybe Bigfoot will even be implicated. Maybe the mastodon was killed by Atlanteans. Onward.  MiG-17. I shall return. MiG-17. I shall return. The annual meeting of the Society for American Archaeology (SAA) is going on right now in Orlando. I made the 6.5 hour drive down from Columbia, SC, on Thursday. It took me closer to 8.5 hours, though, because I called an audible and went to visit the birth town of Barnwell, SC, after hearing a story on NPR about James Brown as I was starting my trip. And then I stopped to look at a MiG-17 in the parking lot of the Mighty Eighth Air Force museum in Savannah, GA. It was the B-47 Stratojet visible from I-95 that caught my attention. I didn't actually go in the museum, but you understand why it sometimes takes me a while to get from Point A to Point B when I travel alone. I'm guessing that most people that read my blog are not professional archaeologists and have never been the SAA's. These are the annual meetings of the largest professional archaeological organization in the country. I don't have any numbers on annual attendance, but for archaeologists these meetings are a chance to meet new people, learn new things, talk about ideas and data, and re-connect with others in our social networks. The array of presentations and posters that one can go to over the course of several days is large (here's the program for this year's meeting). So you have to make choices about how you're going to spend your time. I just wanted to pass on a few interesting things that I've seen, heard, or thought about over the last couple of days. An Early Holocene Shaman Burial from Texas Margaret (Pegi) Jodry gave a really interesting presentation on an 11,100-year-old (ca. 9,100 BC) double burial (a male and a female) from Horn Shelter No. 2 in Texas (you can find the 2014 paper that discusses the burial here). Human remains from the Late Pleistocene/Early Holocene are extremely rare in North America. The male burial is particularly interesting because it appears, based mostly on the analysis of the contents of the grave, to be the internment of a shaman. The burial includes tools probably used for making pigment (antler pestles and turtle shell bowls), a tool for applying pigment to the skin, and a scarification tool. The burial also included animal remains that probably had symbolic significance: hawk claws and badger claws were found in the vicinity of the head and neck, presumably placed there as part of the burial ceremony. Jodry speculated that the hawk and badger may have symbolized travel to the "upper world" (sky) and "lower world" (underground), respectively. I found Jodry's discussion of this burial to be really interesting after recently hearing my SCIAA colleague Adam King talk about Mississippian (ca. AD 1000) iconography and cosmology. I wondered how far back in time we might be able to trace the basic cosmological elements that we can discern (with the help of linguistic data) as important to the Mississippian world. The Hon Shelter burial seems to provide a tantalizing glimpse of the symbolic representation of a tripartite "above" "earth" and "below" cosmos in the Early Holocene, associated with a a projectile point technology (San Patrice) that is related to the Dalton points that are the most common markers of the Late Paleoindian period in the Southeast. Very interesting. The Indiana "Mummy:" Still Not a Mummy  If you remember last summer's flap over the supposed "mummy" discovered in Lake County, Indiana, (I wrote about it here) you will be interested to hear that I ran into the archaeologists who were working at the site when the human remains were found. As I suspected (which I can't remember if I ever wrote about), the site was one that I had actually worked on in the past: I participated in the Phase II testing of the and others back in the winter of 2004 (you can see a copy of the report by Sarah Surface-Evans and others here). Anyway, James Greene, an archaeologist with Cardno Envionmental Consultation Company, told me that what they encountered was a flexed human burial dating to the Woodland period. The remains were left in place and reburied in consultation with Native American groups. As reported in this story from July 2, the sheriff erroneously described the remains to the press as "mummified." They were not. There was no mummy, and there was no cover-up about a mummy. Icebergs on the Carolina Coast?  I've seen a lot of papers over the last couple of days about climatic/environmental change in the Late Pleistocene and Early Holocene. The amount of information that we have now is amazing, and the datasets relevant to understanding recent environmental change continue to diversity and develop (pollen, beetles, ice cores . . .). At a paper by James Dunbar (unfortunately he wasn't there to actually give it, so I didn't get to talk to him about it), I learned about something called the "Georgetown Hole." This is a spot along the submerged continental shelf off the coast of South Carolina that apparently preserves evidence of icebergs running aground (you can read about it on this page, which is also where I got the image and the quote below). The "scour" marks going from the Georgetown Hole toward the coast were reportedly created by the bottoms of icebergs scraping the continental shelf: "The location and orientation of the keel marks suggests icebergs were entrained a southwestward flowing coastal current, most likely during the last glaciation. This may be the first evidence of iceberg transport to subtropical latitudes in the north Atlantic." Apparently these marks were just discovered in 2006/2007. If I understood Dunbar's paper correctly, there is still no firm answer on exactly when these marks were created. I think (and I'm really not sure, because I was still trying to wrap my head around the image of icebergs drifting by Charleston) Dunbar was suggested this may have been occurring rather late in the Pleistocene, perhaps even associated with the Younger Dryas (about 12,900 to 11,700 years ago) and the environmental changes associated with it. Disney World Not Such a Magical Place for a Conference I'm not sure what the decision-making process was for choosing a Disney resort as a conference location. Although I'm only offering my own opinion here, I can tell you that many people here agree with me. It's too expensive. I paid $16 for a pre-made chicken sandwich and a coke for lunch today. A pint of beer at the hotel bar is like $8 or so. The hotel rooms are over $200/night. It's impossible to go elsewhere to eat lunch, because we're on a Disney campus. Everything is Disney and everything is expensive unless you want to get in your car and drive somewhere for lunch, in which case you won't make it back in time to make the beginnings of paper sessions in the afternoon. You could argue that this is a "family friendly" location for a conference, but the SAA elected not to provide any childcare services this year. Maybe this is a great place to vacation, but my opinion is that it is a poor choice for a working conference where many of the attendees are here with limited funding and/or on their own dime. To Be Continued . . .

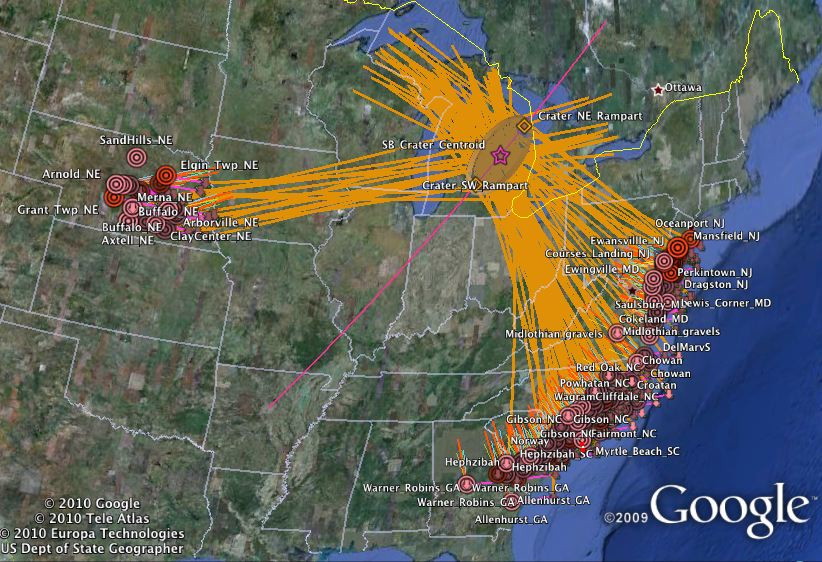

I'm going to cut if off for now and get back to the business of the conference. I saw a good session this morning that was organized by Erick Robinson, Joe Gingerich, and Shane Miller ("Human Adaptations to Lateglacial and Early Holocene Climate and Environmental Changes"), but I'm hoping to talk to some of the participants more later. It was good stuff. A comment on yesterday's blog post about the Middle Archaic brought up the issue of the origin and age of the Carolina bays. The bays are elliptical depressions with a northwest-southeast orientation. They vary significantly in size and occur along the Atlantic coast in a band extending from New Jersey to Florida. There is a similar set of features (with different orientations) in Nebraska and Kansas.  Carolina bays in North Carolina (Wikipedia). Carolina bays in North Carolina (Wikipedia). Carolina bays are interesting for several reasons. They're obviously peculiar, geographically-widespread features formed by some sort large scale event or natural process. There is significant disagreement as to how and when formed and, subsequently, their relationship to the early prehistory of the Eastern Woodlands. The most dramatic scenario sees the Carolina bays as impact sites from debris that rained down after an apocalyptic comet strike 12,900 years ago that triggered the Younger Dryas and caused the "extinction" of the Clovis peoples. The less dramatic scenario sees them as results of some regular terrestrial process that ran its course well before humans were even present in the region. How did the Carolina bays form? Today there are two main schools of thought about how the Carolina bays formed: (1) through wind-wave action associated with Pleistocene conditions unlike those of today; and (2) as impact sites of debris ejected by a comet strike in Michigan or Canada. My impression is that the geomorphological (i.e., terrestrial) explanation enjoys a lot of support from geologists who specialize in the Pleistocene. I'm just going to paste in a paragraph from the Wikipedia entry that sums it up: "Quaternary geologists and geomorphologists argue that the peculiar features of Carolina bays can be readily explained by known terrestrial processes and repeated modification by eolian and lacustrine processes of them over the past 70,000 to 100,000 years. Also, Quaternary geologists and geomorphologists believe to have found a correspondence in time between when the active modification of the rims of Carolina bays most commonly occurred and when adjacent sand dunes were active during the Wisconsinan glaciation between 15,000 and 40,000 years (Late Wisconsinan) and 70,000 to 80,000 years BP (Early Wisconsinan). In addition, Quaternary geologists and geomorphologists have repeatedly found that the orientations of the Carolina bays are consistent with the wind patterns which existed during the Wisconsinan glaciation as reconstructed from Pleistocene parabolic dunes, a time when the shape of the Carolina bays was being modified." The second proposition -- that the bays were formed in connection with an extraterrestrial impact -- is the more exciting one. It has been around for a while in various forms (so far the earliest paper I've seen dates to 1933; here is a paper from 1975). Proponents of this idea point to the elliptical shape of the bays, their peculiar orientations and limited geographic distribution, and other characteristics that appear difficult to explain using the terrestrial model (why, for example, do similar features occur in Nebraska?). This page proposes that " . . . a catastrophic impact manifold deposited a blanket distal ejecta up to 10 meters deep in a set of butterfly arcs across the continental US. We have modeled the blanket as a ballistically deposited hydrous slurry of sand and ice originating from a cosmic impact into the Illinoisan ice sheet, and propose that Carolina bay landforms were created during the energetic deflation of steam inclusions at the time of ejecta emplacement."  Orientations of Carolina bays and similar features in Nebraska used to suggest impact site at Saginaw Bay (page reference in text). Orientations of Carolina bays and similar features in Nebraska used to suggest impact site at Saginaw Bay (page reference in text). In other words, an oblique comet strike on the continental ice sheet (this paper says the orientations of the bays suggest the impact site was located at Saginaw Bay, Michigan) and ejected into the air a massive load of sand and ice. That debris landed in an pair of arcs, one stretching across the Atlantic coastal plain and forming the Carolina bays. You'll notice I have bolded the word "Illinoisan" in the quote above. That brings us to the next question. When did the Carolina bays form?

Multiple lines of evidence suggest that, even if the Carolina bays were the result of an extraterrestrial event rather than terrestrial processes, they formed long before humans were present in eastern North America. The Illinoian stage of the Pleistocene referenced above dates to about 190-130 thousand years ago. This paper by Mark Brooks et al. (2001) discusses stratified sequences of natural deposits in a Carolina bay that have been directly dated by radiocarbon to tens of thousands of years before the Younger Dryas (12,900 years ago) impact proposed by Firestone et al. (2007). That paper also details encroachment of a sand dune over and into a Carolina bay at around 48,000 years ago, indicating that the bay has to be older than 48,000 years. Because many Carolina bays held water, they were attractive to both animals and humans in the regions they occurred. This 2010 paper (also with Mark Brooks as senior author) describes the presence of archaeological sites associated with Carolina bays near the Savannah River. Clovis artifacts are associated with the bays, which means that the bays could not have been the result of some event that "wiped out" the Clovis peoples: the bays were there before, during, and after the Early Paleoindian period. Conclusion I used "terrestrial or extraterrestrial" in the title of this post because I thought it would attract readers. While I'm curious about that question, however, it doesn't ultimately appear to have much bearing on the early prehistory of the Eastern Woodlands. The Carolina bays, however they were formed, predate the Paleoindian period by at least tens of thousands of years - there's a lot of positive evidence for that. Even if a comet strike at about 12,900 years ago did precipitate the Younger Dryas and cause environmental changes to which human societies would have had to adjust, that impact did not produce the Carolina bays. No-one would have been around to experience the effects of a very ancient (e.g., Illinoian age) impact into the ice sheet. Maybe I should have titled this post "If a comet hits the ice but there's no-one around to see it, does it make a difference?" It does, of course, if it re-shaped the environment in some way that was significant to later peoples. But I don't think it is those kinds of effects that most extraterrestrial impact fans are excited about. |

All views expressed in my blog posts are my own. The views of those that comment are their own. That's how it works.

I reserve the right to take down comments that I deem to be defamatory or harassing. Andy White

Email me: [email protected] Sick of the woo? Want to help keep honest and open dialogue about pseudo-archaeology on the internet? Please consider contributing to Woo War Two.

Follow updates on posts related to giants on the Modern Mythology of Giants page on Facebook.

Archives

January 2024

Categories

All

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed