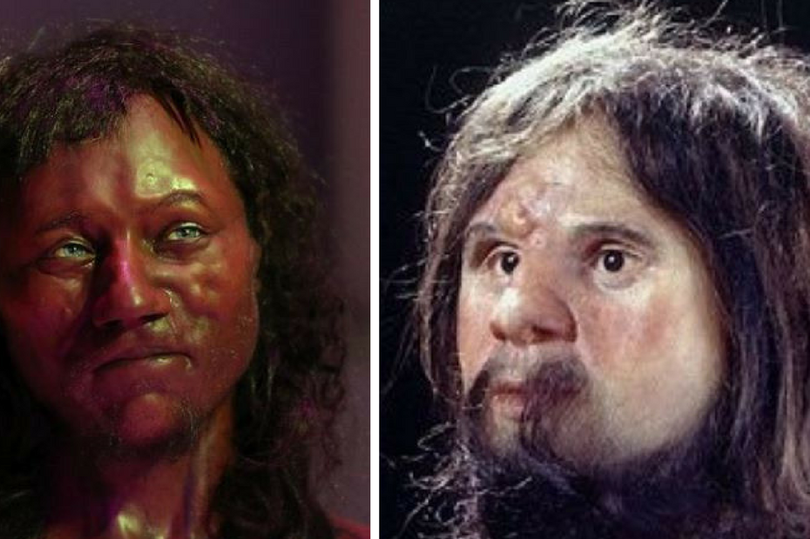

These blanket rejections of the science responsible for Cheddar Man's new look come from the same crowd that, just two weeks ago, hailed the announcement of a 200,000-year-old "modern human" fossil from Israel as a significant blow to the Out of Africa theory. Oh you fickle racists.

In reality, the claim that a European from the Early Holocene probably had dark skin and blue eyes is unsurprising in light of other recent work suggesting that lightened skin pigmentation emerged relatively recently in European populations. These conclusions are not the result of agenda-driven guesswork, but of direct analysis of DNA. Have a look at the paper from the La Brana specimen for an example.

Data on the recent emergence of "whiteness" among European populations undercuts the white supremacist notion that light skin tone is ancient, "special," and somehow linked to inherent biological/cultural superiority. It's a very short step from the modern mythologies of white supremacy into numerous threads of pseudo-archaeology, many of which depend on the existence of ancient "white gods," "white giants," "white Atlanteans," etc.

The real stories of human variability are much more interesting than the fantasy ones. I recommend embracing evidence.

RSS Feed

RSS Feed