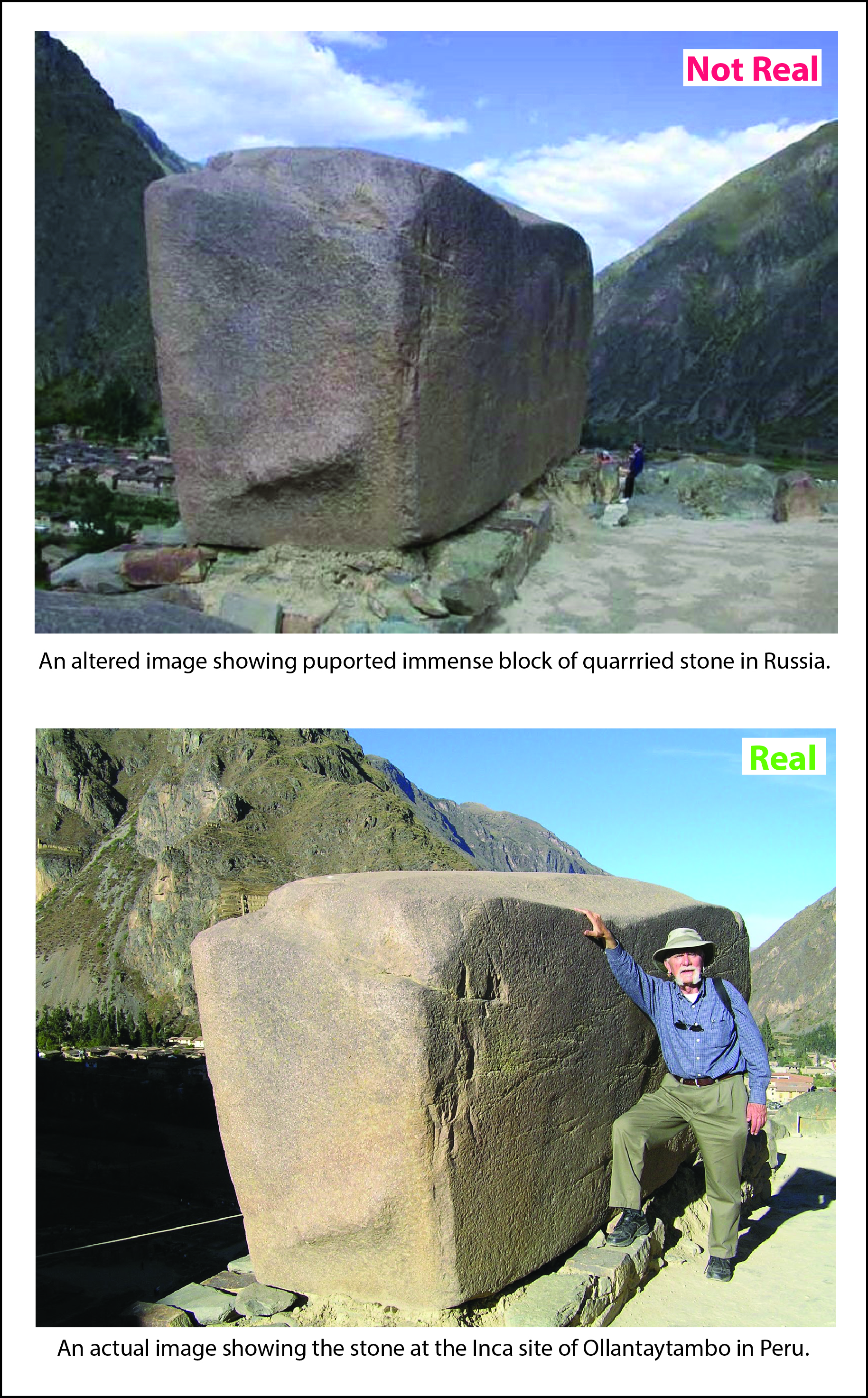

The picture isn't real, of couse. It took less than 60 seconds of searching on my phone while having a cup of coffee to find that the stone shown in the image is actually a quarried block at the Inca site of Ollantaytambo, Peru. I found a nice picture of the block on this website. It's a big block of stone, sure, but nowhere near as large as the image that was manipulated to produce false "evidence" to use as clickbait. Ethnography and achaeology shows us that people in non-industrial societies all over the world were and are able to move rocks of this size using human power and ingenuity.

|

This morning on one of the Facebook groups I follow I saw this image, labeled simply "Russia:" The discussion about the stone leap-frogged right over the authenticity issue, skipping straight to the part where we muse about the anti-gravity technologies that Ice Age civilizations must have had to move such an enormous rock. The picture isn't real, of couse. It took less than 60 seconds of searching on my phone while having a cup of coffee to find that the stone shown in the image is actually a quarried block at the Inca site of Ollantaytambo, Peru. I found a nice picture of the block on this website. It's a big block of stone, sure, but nowhere near as large as the image that was manipulated to produce false "evidence" to use as clickbait. Ethnography and achaeology shows us that people in non-industrial societies all over the world were and are able to move rocks of this size using human power and ingenuity. I wonder when and if the world's respect for reality will re-emerge.

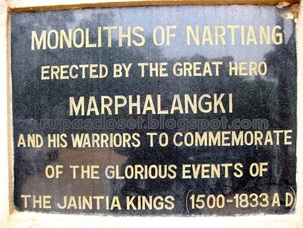

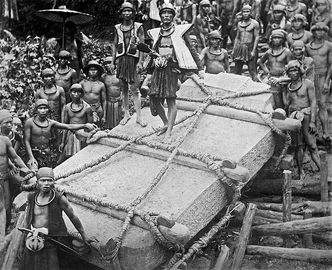

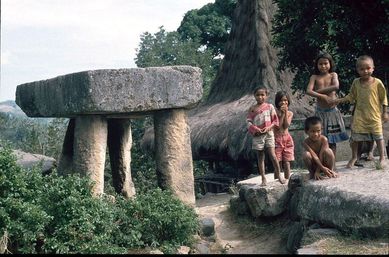

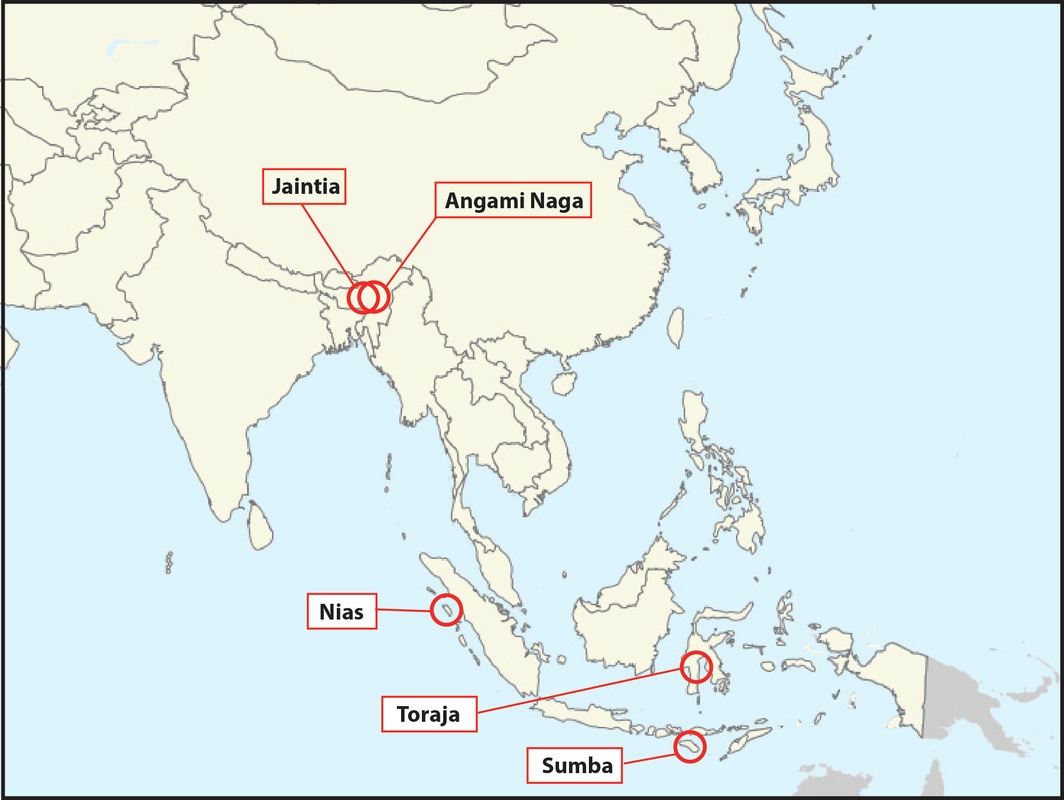

My interest in the megalithic traditions of south and east Asia began in reaction to the ridiculous claim/belief that it was impossible for normal-sized people without advanced technology to have moved the large stones associated with prehistoric megalithic traditions (hence they must have been built by giants, aliens, advanced civilizations, etc.). The "living" megalithic traditions of Indonesia (Sumba, Nias, Toraja) and India (Angami Naga) are great because they clearly show not only that large numbers of people armed only with ropes and wood can move some pretty big stones. They also give us insight into the contexts and motivations that make moving those stones possible. There is both early 20th century ethnographic information and, in some cases, videos available on YouTube showing stones being moved. If you're interested in this sort of thing, check out my previous posts: the photographs and the videos are pretty sweet. My interest in the Asian megalithic traditions has started to move beyond simply using them to demonstrate that normal-sized people can move big rocks. As I've learned a little bit more about the archaeology/ethnography of this part of the world, I've started to see the potential for building a really interesting case that might form a useful comparison/contrast to the prehistoric megalithic cultures of Europe and the Mediterranean and the earthen structures of eastern North America. So . . . perhaps I'm off on another large database project. Who knows. For now I just wanted write a note about the megalithic monuments of Nartiang,India. My knowledge of the geography of south/east Asia is not great, and I'm guessing that's true for many of the readers of this blog, also. So I made a map showing the locations of the megalithic traditions I've written about so far: The site of Nartiang is in the Jaintia Hills region of eastern India, in the state of Meghalaya. It is just one of many sites in the region with megalithic monuments. I do not yet fully understand what is known about the living/prehistoric megalithic traditions of this area, but I was struck by the explanations for the monuments at Nartiang (the following passage is from this paper by Vinay Kumar): "The megalithic monuments of Nartiang in Meghalaya are significant because of larger dimension. Some of the monuments are very big even 9m high. Nartiang used to be the summer capital of the Jaintia Kings of the Sutnga State. The megaliths here are huge granite slabs probably hewn out by the fire setting method. The huge monolith, is said to be erected by Mar Phalyngki, a Goliath of yore. The Nartiang menhir measures 27 feet 6 inches in thickness." Here is a photo of Nartiang (source): Many of the monuments at Nartiang are composed of a combination of a standing stone (menhir) and horizontal slab balanced on supports (dolmen). In other areas (and apparently this one as well), the vertical and horizontal stones symbolize male and female, respectively.  Based on a quick perusal of online descriptions, it appears as if the prevailing belief is that the Nartiang monuments were erected during the reign of the Jaintia kings in the 16th-19th centuries (source for the photo to the left). An individual named Mar Phalyngki or Marphalangki is variously credited with building all of the monuments or the biggest monument, and is sometimes described as a "giant." As I said above, I don't have enough knowledge of the ethnohistory or archaeology of this region to evaluate the claim that the monuments were built by the Jaintia kings. I will just point out that the clustered arrangement, the repeated male/female motif, and the variety of stone sizes all seem to me to be consistent with the "living" megalithic traditions that are related to prestige-building and funerary rituals (i.e., celebrating/commemorating particular individuals or households by harnessing human capital to move and erect large stone monuments). I'm hoping there's a lot more information available on the megalithic cultures of this region. I don't know exactly how many societies in the world have "living" traditions of megalithic construction, but here is another one: the Toraja people of South Sulawesi, Indonesia. If you're keeping score at home, this is the fourth group I've discussed (the others are the Angami Naga of India and the megalithic traditions of Sumba and Nias in Indonesia). If you have any doubt that lots of people with some wood and rope can move some pretty big rocks, you should watch some of the videos from the Naga and Sumba cases, or look at the early 20th century photographs from Nias.  Menhirs at Bori Parinding. Menhirs at Bori Parinding. The Toraja erect menhirs (standing stones) as monuments for the deceased. In a paper in this 2006 edited volume titled Archaeology: Indonesian Perspective, Retno Hondini explains the connection between status in life and treatment at death: larger, more complex, and more expensive funerals are performed for higher status individuals. These funerals include several ceremonies, one of which involves moving and erecting menhirs (Hondini 2006:551): "Mangriu batu is a stone-pulling ceremony. The stone then functions as a menhir (simbuang), a symbol that a ceremony has been performed for the deceased. Every burial ceremony, particularly those of an aristocrat, always includes the manufacture of a menhir (simbuang). The raw materials to make menhirs are usually available in the surrounding environment. The chosen stone is pulled by a large number of people from its original place to the place where the ceremony is to take place (rante). After the stone arrives at the rante, a menhir (mesimbuang) is then erected" I've been able to find just a few videos of stone-pulling among the Toraja. This one is of poor quality, but shows a stone (maybe 3m long?) being pulled into a village and erected using ropes and poles. This video shows a smaller stone being pulled by a relatively small group of men (a second video shows another stone being moved). I'm no expert on South Asian megalithic traditions, but I feel comfortable pointing out the positive relationships between status/wealth, the ability to mobilize/support human labor, and the size of the stones moved in the four cases I've looked into so far. I'm not saying those relationships explain all the megalithic monuments erected by prehistoric non-state (e.g. Neolithic) societies, but it's a much more reasonable place to start than giants or aliens. Or giant aliens. References

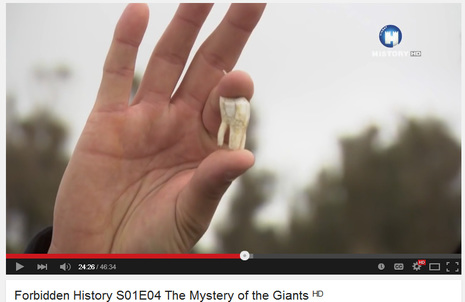

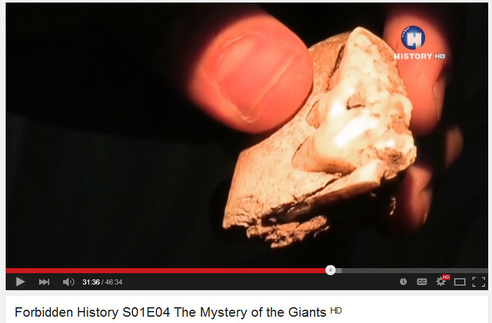

Handini, Retno. 2006. Stone Chamber Burial (Leang Pa'): A Living Megalithic Tradition in Tana Toraja, South Sulawesi. In Archaeology: Indonesian Perspective, edited by Truman Simanjuntak, M. Hisyam, Bagyo Prasetyo, and Titi Surti Nastiti, pp. 549-557. Jakarta: LIPI Press. Simanjuntak, Truman, M. Hisyam, Bagyo Prasetyo, and Titi Surti Nastiti (editors). 2006. Archaeology: Indonesian Perspective. Jakarta: LIPI Press. My main geographic interest in the "giants" phenomenon lies in North America, especially the Eastern Woodlands. While the situation here has its own sets of linguistic, historical, political, religious, cultural, and scientific dimensions that make it unique, it doesn't exist in isolation. Beliefs in giants, both in the past and today, articulate with religion, culture, and archaeology in many parts of the world. So far I've made just a few excursions outside of North America: I've discussed what size differences depicted in ancient Egyptian art might mean, looked an actual case of pituitary gigantism from ancient Rome, and talked about ethnographic examples of megalithic traditions in India and Sumba and Nias in Indonesia. Today we're going to Sardinia. Sardinia is a large island west of the Italian Peninsula. Human occupation of the island dates to at least the Upper Paleolithic. Neolithic and Bronze Age peoples built stone constructions on the island, some of which were "megalithic" in that they made use of very large stones. I'm not an expert on Mediterranean prehistory, but a quick review of information online makes it clear there is a lot of variability in the rock architecture of Sardinia. The megalithic traditions on Sardinia overlap with those in other parts of Europe in terms of their timing and some of their architectural elements, but also have aspects that make them distinctive. There is a current folk belief in ancient giants on Sardinia that appears to have a lot in common with the situation in North America. Just about everything I know about the belief in giants on Sardinia I am basing on this episode of the program Forbidden History, a 2014 series (produced in the UK) that says it "uncovers the truth behind great myths, conspiracy theories, ancient treasures, lost civilisations and war time secrets." Like similar programs produced in the US, much of the emphasis is on travel and making the host appear intrepid. But this episode, at least, does reveal some interesting things about the belief in giants in Sardinia.  Screenshot from "Forbidden History" showing one of the megalithic tombs on Sardinia that local tradition holds was built by giants. Screenshot from "Forbidden History" showing one of the megalithic tombs on Sardinia that local tradition holds was built by giants. The Sardinian tradition of giants is tied to the megalithic architecture on the island. Commonalities to the North American situation are striking: a folk belief based partly on "mysterious" architecture; stories of finding the remains of giants passed down through generations or remembered from childhood; the idea that mainstream science and the government are actively suppressing the truth; and an almost absolute lack of direct physical evidence. The only purported physical evidence of the remains of giants in Sardinia that I have come across is teeth. I found four examples: two from the Forbidden History episode and two promoted by a UFO enthusiast trying to insert extraterrestrial visitors into Sardinia's prehistoric past. In the first two of these cases I discuss, it is asserted that the teeth are human, but we are not permitted to actually see the teeth in detail. Based on what is shown, the teeth do not appear to me to be human. In the other two cases, just like the "replica" of the Denisovan tooth shown by Search for the Lost Giants, the teeth don't look anything like human teeth - anyone who knows anything about teeth wouldn't mistake them for being human in thousand years.  Screenshot from "Forbidden History" showing a purported giant's tooth. Screenshot from "Forbidden History" showing a purported giant's tooth. Tooth 1: Donated by an Intimidated Informant The first tooth is shown to us on Forbidden History (beginning about 24:00 into the episode). The host waves the tooth around for a while, explaining that it was given to him by a farmer who refused to be interviewed because "he'd been warned off talking to us . . . we're not sure by whom or why." The farmer claims it is a giant's tooth. The screenshot to the left shows the best view we are given of the tooth. We never get to see the occlusal surface (the part of of the tooth that comes into contact with other teeth), so all we have to go are the shape and proportions of the crown and the roots and the fact that there are three roots. In the human dentition, the first and second maxillary molars (the grinding teeth on the upper jaw) are the only teeth that routinely have three roots. Sometimes mandibular molars have three roots instead of the usual two. Anyway, based on what we are shown, it appears to be unlike any human molar tooth I have ever seen. The crown appears rather tall, and the proportions and the crown and the roots just don't look right to me. I suspect anyone with a rudimentary working knowledge of comparative dental anatomy would be able to quickly identify this tooth to the family level (i.e., whether it belonged to a cow, a deer, a pig, etc.) by looking at the cusps. Maybe that's why the TV show doesn't actually let us see the occlusal surface.  Screenshot from "Forbidden History" showing a purported giant's jaw examined by a dentist. Screenshot from "Forbidden History" showing a purported giant's jaw examined by a dentist. Tooth 2: The Testimony of a Dentist The second tooth (actually a set of teeth) is also shown to us by Forbidden History (beginning about 30:00 into the episode). The host interviews a dentist who claims to have analyzed a piece of bone containing three "very big molars" reportedly recovered from one of the "giant's tombs." We are later told that the actual specimen is no longer available, having mysteriously disappeared after being given to the university in Cagliari. So we are left with the dentist's recollections and a video taken while he was analyzing the specimen. The bone fragment appears to be part of a mandible. We don't get to see the fragment with a scale (or in a good quality photograph), but the dentist states that one of these teeth was 30 mm and another was 35 mm (presumably those are mesial-distal length measurements). What we are shown of the video is so poor that it is hard to tell anything about the teeth - the light is bright and most of the detail is washed out. I messed with the contrast in Photoshop to try to bring out some of detail in the cusps of the teeth but it wasn't a great improvement. The teeth appear to be bunodont (crowns that have rounded or conical cusps), which you find in the molars of omnivores such as humans, pigs, and bears. Since we never get a good look at the cusps, it is hard to say what creature these teeth belonged to. Based on looking at some publications on European fossil pigs (such as this one) I'd say a pig is a reasonable guess. Again, it's hard to fathom why there is no single good, well-lit, scaled photo of this specimen that could be shown. If I was given a piece of evidence that I thought would change history, I'm pretty sure I'd take a picture. I'm certainly not buying this as a human jaw based on what I saw on Forbidden History.  Photograph of a purported "giant's tooth" from Paola Harris' website (cropped and adjusted). Photograph of a purported "giant's tooth" from Paola Harris' website (cropped and adjusted). Tooth 3: Authenticated by a UFO Journalist The third tooth is touted as a "giant's tooth" on the website of UFO enthusiast Paola Harris. It's nothing of the sort: it's an animal tooth that very clearly shows a pattern of enamel ridges looping around the occlusal surface and protruding from the dentine. This is called a "lophodont" or "secodont" tooth and is found in a wide variety of herbivores, including horses, rhinos, tapirs, cows, and deer. Humans do not have these kinds of teeth. The image of the tooth I show here is cropped and adjusted to bring out the cusp pattern more clearly. I don't know exactly what creature we're looking at here, but I can tell you with 100 percent confidence that this is not a human tooth. Someone with better skills in comparative dental anatomy will be able to identify this easily from the photo.  Photo of purported "giant's jawbone" from Paola Harris' website. Photo of purported "giant's jawbone" from Paola Harris' website. Tooth 4: Another Paola Harris Special Paola Harris' website also features a photo titled "giant jawbone" that is apparently supposed to show the jawbone of a human giant. It is part of a mandible with portions of three teeth visible. The bone and the teeth are in poor condition, but the high quality photograph makes it apparent that the specimen is not human. The morphology of what's left of the teeth suggests, again, some kind of large herbivore. The opening of this episode of Forbidden History features the host riding in helicopter in order to ask why so many ancient cultures have tales of giants. Accompanying this question is a montage of well-known fake photographs of giant skeletons that have been passed around the internet for years. That pretty much sets the tone for what follows. At one point they even show someone posing with Joe Taylor's femur sculpture. This program, like Search for the Lost Giants, could do a lot more "discovering of the truth" if it spent more money on paleontologists and less money on helicopter rides. If they wanted to identify the teeth, they certainly could have (at least the one that the host was holding in his hand).

Here's a tip for all you "truth seekers" out there: learn something about your subject matter, or ask someone who already knows something. Dentists and physicians are not your best bet, either: neither typically needs to recognize and identify bones and teeth outside of the human body (why would they?), and neither usually has even basic training in how to do that. Variation in animal teeth has been studied for a long time, and there are plenty of archaeologists, anatomists, and paleontologists who know a lot about the teeth of various animals as well as the teeth of humans. These people, unlike dentists, physicians, and coroners, can recognize and identify remains that are not human because they are (1) actually trained to first ask the question "is it human?" and (2) equipped with practical knowledge of how to answer that question. I have nothing against farmers, journalists, TV producers, dentists, and UFO enthusiasts, but I do not trust their determinations of what's a human tooth and what's not. And neither should you. If this is the best evidence giant enthusiasts can offer for Sardinia . . . it's probably time to move on. Earlier today I wrote this post about some pretty sweet early 20th century photographs from a megalithic stone-pulling ceremony on the island of Nias, Indonesia. I found some additional photos and (I think) figured out a few things that I wanted to pass on. I could be wrong about some of this - if I am please let me know.  A. A. First, I'm now 99 percent sure all the photos show the same stone being moved. If you look carefully at the first photo of the stone (A), you'll notice it has been shaped. There is a raised area on the "upstream" end, which itself includes another raised area in the center. The corners of the stone are rounded. Those same features can be seen on the other stone-pulling photos, convincing me that all the photos are of the same stone. I think all the photos come from a two volume 1917 publication entitled Nias: Ethnographische, geographische en historische aanteekeningen en studien, by E. E. W. Gs. Schroeder. From what I gather, one of the volumes is text while the other is photographs. I don't have access to either at the moment (let me know if you have it?), but I'm guessing all the Nias stone-pulling photos in the previous post come from the volume of photographs. Second, I found an additional photo of the stone in the village of Bawömataluo on Alain Testart's website. It shows a line of slaughtered pigs in the street near the stone. Third, I think that the stone shown in the photographs is the horizontal stone on the left in the photo of Bawömataluo below (source). The stone has been smoothed and carved, but notice the two-level raised portion at the end.  C. C. The two large horizontal stones and the standing stones behind them are in front of the Omo sebua (chief's house) in the village. The pillar on the right and the stone in front of it can be seen in the photograph (C) that shows the newly-pulled stone and sled. On the left side of photograph C, people are sitting on an existing horizontal stone. On the right side, people are sitting where the new stone will be positioned. To move the new stone into position, it will have to be slid toward the chief's house from where it is "parked" (but it is oriented correctly with the raised portion facing the existing stone. A panoramic view of Bawömataluo (D) shows the chief's house in relation to the stone that is used for the Hombo Batu (stone jumping) ritual (down the street to the left). In Hombo Batu, young males jump over the stone (which is over 2 m high) in order to prove that they are adults (and/or worthy of being warriors). This is still done today and is apparently a tourist attraction, as it is easy to find numerous photos online. This video has some nice, high quality footage of the village and shows a man jumping over the stone. This video offers an explanation of the tradition and some background on competitive feasting and conflict on Nias.  E. E. The Hombo Batu stone in Bawömataluo can be seen to the left in photograph E. The place where the new stone will be positioned can be seen to the right. In photograph E t appears as though there is a thinner slab of stone already resting on the supports where the new stone will be placed. This whole scenario may be explained completely (perhaps with additional photos) in Schroeder's ethnography or in some other source. I hope I can have a look at it some day. According to this desciption submitted to UNESCO by The Ministry of Culture and Tourism of the Republic of Indonesia, the horizonal stones represent males and the vertical stones represent females. Saonigeho (or Siliwu Gere) was the individual who finalized the construction of the chief's house. Normal-Sized People Can Move Big Rocks: A Quick Note on the Megalithic Traditions of Nias, Indonesia3/28/2015

This is a quick post to bookmark some information about the megalithic traditions of Nias, Indonesia. Unlike the megalithic traditions of Sumba (Indonesia) and the Naga people (India), the behavior of moving big stones appears to be no longer "living" on Nias. The 2007 publication Megalithic Traditions in Nias Island states that the tradition of moving large stones was alive on Nias until the 1950s (page 10). The excellent photo above (source), taken around 1915, shows a large stone being moved in the village of Bawomataluo. Searching on "Bawomataluo" turned up the photo below (source), which shows a large stone on a sled in the right portion of the photo. Based on a Google translation of the caption, this appeared to be a photograph of a celebration related to moving a stone in honor (?) of a person named Saonigeho. Searching on that name turned up the two great photos of stone-pulling below (from the website http://www.geheugenvannederland.nl). Here is the source for the first photo, here is the source for the second. Based on the size of the rock, its shape, and the details of how the stone is attached to the sled, I'm pretty sure all of these photos are showing the same stone. More work will show whether or not that's correct. Looking carefully I found another photo that appears to also show the same stone on the sled (source): Addendum (3/28/2015): I found out a little bit more about the stone, the town, and the original ethnography that I presume the photos are from (see this post).

Relatively small megalithic structure in Sumba, Indonesia (photo from here: http://www.hpgrumpe.de/reisebilder/index.html) Relatively small megalithic structure in Sumba, Indonesia (photo from here: http://www.hpgrumpe.de/reisebilder/index.html) Adding to the accounts and video of the Naga moving and placing multi-ton menhirs with ropes, sleds, rollers, and a lot of people, I present the case of the megalithic tombs of Sumba, Indonesia. Much of the information in this post comes from the scholarly work of Ron L. Adams, currently with Simon Fraser University and AINW. Adams has written several papers based on his ethnoarchaeological fieldwork among the peoples of West Sumba in the late 1990s and early 2000s. Some of those papers discuss the ongoing practice and contexts of the construction of megalithic tombs. This is great information for understanding why people might build megalithic structures. As in the Naga examples, large stones are are quarried, moved, and placed in an environment of competition and prestige-building. Bigger is better: the grander the structure, the larger the stones, the more it "costs" in terms of human capital and the resources to support that capital. Building a megalithic tomb is a way to display wealth and influence. The West Sumba data also provide another example of how people move big rocks. Spoiler alert: It doesn't involve giants, supernatural levitation, or alien technology. It involves, rather, lots of people armed with ropes, wooden skids, and rollers (pretty similar to the example from India). In his paper "Transforming Stone: Ethnoarchaeological Perspectives on Megalith Form in Eastern Indonesia," Adams describes how it's done: "The traditional method for transporting megalithic stones in Sumba is to haul them atop wooden sledges (tena watu) (Fig. 9.3). A sledge with its attached stone is pulled using vine ropes, requiring between 100 and 1000 people for the large capstones or standing kado watu stones, while lesser numbers are needed to move the stones for the tomb walls (50-100 people). It can take from one day to nearly one month to transport the largest stones in this manner from a quarry to the tomb owner's village, depending on the size of the stone and the distance to be travelled. Each day the stone is moved, several pigs, and at times water buffaloes, are slaughtered to feed the stone haulers and the spectators who are invited to view the proceedings. The labour for this endeavour typically comes from the tomb owner's clan as well as from other allied clans" (page 85). It took a while, but I finally found some videos online (the key was figuring out that a name for the stone-pulling ceremony was tarik batu). This video shows a really large group of people preparing and pulling a pretty big stone. Rather than a long, sustained pull, they get the stone moving rapidly in short bursts. This one also shows the removal of the stone from the quarry. I also found a few other things of interest. This video shows a crew working to remove a stone from a quarry. This video shows a funeral, and (about 3:00 in) some stills of a stone on a sled. This video shows a funeral which (at about 22:00 in) includes using long poles as levers to lift the capstone of a megalithic tomb so the body can be interred.  Megalithic tomb at Gallubakul, with vacationers shown for scale. It is the horizontal stone that is reported to weigh 70 tonnes. Megalithic tomb at Gallubakul, with vacationers shown for scale. It is the horizontal stone that is reported to weigh 70 tonnes. As in the Naga case, these are not small rocks being moved. In this 2010 paper, Adams (page 280) states that the combined weight of the stones making up the largest tombs (which are table-like with legs or sides that support a capstone) can be over 30 tonnes. Based on what little I could find online, the largest stone on the island seems to be one from a tomb in Anakalang (in the village of Gallubakul). The stone (the horizonal slab of the tomb pictured to the right) is estimated to weigh 70 tonnes and measure 5m x 4m x 1m. The story that is repeated online is that it took thousands of men three months to move it. I'm not sure how official that is -- I just found the same story repeated in several places (e.g., The Lonely Planet Indonesia, this website). Whatever the particulars, it is clear that some very big stones were quarried and moved by hand during construction of Sumba's megalithic tombs. Some of the Sumba stones are larger than the largest stones moved to build Stonehenge (about 50 tonnes), larger than the Olmec heads, and larger than many of the Easter Island Moai. The Sumba stones come nowhere close in weight to the largest stones moved by Neolithic societies (The Broken Menhir of El Grah reportedly weighed about 280 tonnes when it wasn't broken). What the Sumba case demonstrates, like the Naga case, is that with access to enough human capital (i.e., the means to support that capital while it is being utilized), only very simple technologies are required to move some pretty big stones. Again, it should go without saying but it won't, so I'll say it: no giants were involved in building the megalithic structures of Sumba.

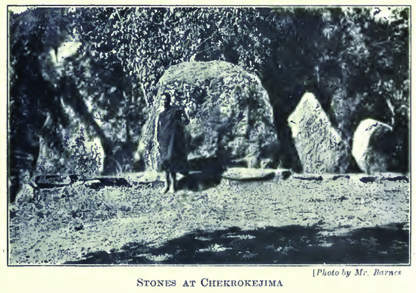

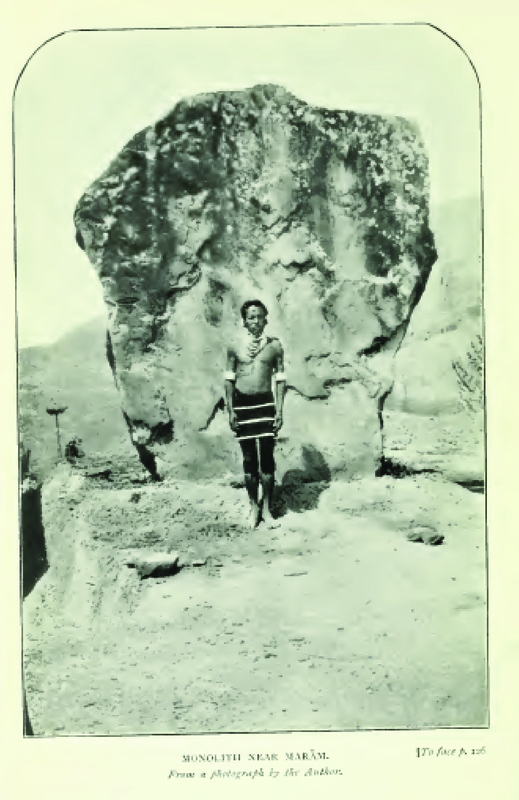

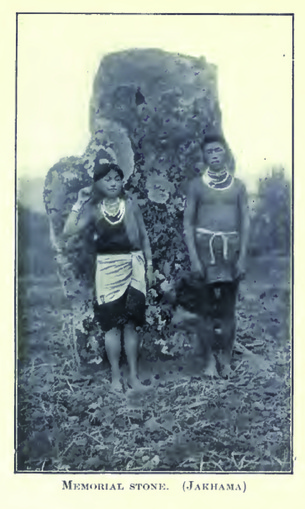

The original ethnographic account of the stone pulling (The Angami Nagas) was by John H. Hutton, published in 1921. I have reproduced two of the photos from that report here and one from a 1911 report (The Naga Tribes of Manipur) by T. C. Hodson (the same stone shown by Flannery and Marcus 2012:108). I don't yet have any specific data on the size of the stones or estimates of their weight, but it's obvious from the photos that they're quite large. The Wikipedia entry for the Maram Naga shows an assemblage of menhirs, presumably erected in stone-pulling rituals. As Flannery and Marcus (2012:109) point out, the stone-pulling rituals of the Naga were performed in the context of societies where “leadership was based solely on achievement.” In other words, not only were these people moving some big rocks, but they were doing it without any centralized, hierarchical organizational structure. It should go without saying (but it probably doesn’t, so I’ll say it), but Hutton did not report that any of the Naga people were giants or in possession of alien technology. Of course, these stones are smaller than many used in megalithic construction. But they compare well in size to some moved by much more "complex" societies, such as the Olmec and the Maya (Flannery and Marcus 2012:109). And they were moved by normal-sized people armed only with ropes and wooden rollers and motivated by community, tradition, and the promise of beer. I think a lot of us can probably relate to that. The giantologists should keep the Angami Naga in mind when they marvel at megaliths. It is probably unwise to assume that a bunch of enthusiastic humans can't figure out how to get a big rock from Point A to Point B. Update (3/7/2105): Post on videos of Naga stone-pulling ceremonies.

|

All views expressed in my blog posts are my own. The views of those that comment are their own. That's how it works.

I reserve the right to take down comments that I deem to be defamatory or harassing. Andy White

Email me: [email protected] Sick of the woo? Want to help keep honest and open dialogue about pseudo-archaeology on the internet? Please consider contributing to Woo War Two.

Follow updates on posts related to giants on the Modern Mythology of Giants page on Facebook.

Archives

January 2024

Categories

All

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed