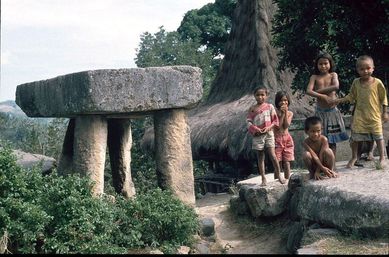

Relatively small megalithic structure in Sumba, Indonesia (photo from here: http://www.hpgrumpe.de/reisebilder/index.html)

Relatively small megalithic structure in Sumba, Indonesia (photo from here: http://www.hpgrumpe.de/reisebilder/index.html) Adams has written several papers based on his ethnoarchaeological fieldwork among the peoples of West Sumba in the late 1990s and early 2000s. Some of those papers discuss the ongoing practice and contexts of the construction of megalithic tombs. This is great information for understanding why people might build megalithic structures. As in the Naga examples, large stones are are quarried, moved, and placed in an environment of competition and prestige-building. Bigger is better: the grander the structure, the larger the stones, the more it "costs" in terms of human capital and the resources to support that capital. Building a megalithic tomb is a way to display wealth and influence.

The West Sumba data also provide another example of how people move big rocks. Spoiler alert: It doesn't involve giants, supernatural levitation, or alien technology. It involves, rather, lots of people armed with ropes, wooden skids, and rollers (pretty similar to the example from India). In his paper "Transforming Stone: Ethnoarchaeological Perspectives on Megalith Form in Eastern Indonesia," Adams describes how it's done:

"The traditional method for transporting megalithic stones in Sumba is to haul them atop wooden sledges (tena watu) (Fig. 9.3). A sledge with its attached stone is pulled using vine ropes, requiring between 100 and 1000 people for the large capstones or standing kado watu stones, while lesser numbers are needed to move the stones for the tomb walls (50-100 people). It can take from one day to nearly one month to transport the largest stones in this manner from a quarry to the tomb owner's village, depending on the size of the stone and the distance to be travelled. Each day the stone is moved, several pigs, and at times water buffaloes, are slaughtered to feed the stone haulers and the spectators who are invited to view the proceedings. The labour for this endeavour typically comes from the tomb owner's clan as well as from other allied clans" (page 85).

It took a while, but I finally found some videos online (the key was figuring out that a name for the stone-pulling ceremony was tarik batu). This video shows a really large group of people preparing and pulling a pretty big stone. Rather than a long, sustained pull, they get the stone moving rapidly in short bursts. This one also shows the removal of the stone from the quarry.

I also found a few other things of interest. This video shows a crew working to remove a stone from a quarry. This video shows a funeral, and (about 3:00 in) some stills of a stone on a sled. This video shows a funeral which (at about 22:00 in) includes using long poles as levers to lift the capstone of a megalithic tomb so the body can be interred.

Megalithic tomb at Gallubakul, with vacationers shown for scale. It is the horizontal stone that is reported to weigh 70 tonnes.

Megalithic tomb at Gallubakul, with vacationers shown for scale. It is the horizontal stone that is reported to weigh 70 tonnes. Whatever the particulars, it is clear that some very big stones were quarried and moved by hand during construction of Sumba's megalithic tombs. Some of the Sumba stones are larger than the largest stones moved to build Stonehenge (about 50 tonnes), larger than the Olmec heads, and larger than many of the Easter Island Moai. The Sumba stones come nowhere close in weight to the largest stones moved by Neolithic societies (The Broken Menhir of El Grah reportedly weighed about 280 tonnes when it wasn't broken). What the Sumba case demonstrates, like the Naga case, is that with access to enough human capital (i.e., the means to support that capital while it is being utilized), only very simple technologies are required to move some pretty big stones.

Again, it should go without saying but it won't, so I'll say it: no giants were involved in building the megalithic structures of Sumba.

RSS Feed

RSS Feed