My new home.

My new home. I've spent much of that two weeks away from my computer, which has been a nice change. Since the semester ended, I've been working in the field, doing stuff around the house and with my family, and prepping my office for a move. Today I'm relocating from the main SCIAA building to a larger, nicer office suite right in the heart of campus. I'll have plenty of room to ramp up my research, process and analyze artifacts, store collections I'm working on, and (hopefully) start getting some student work going. It's really an amazing thing to have the space -- it's larger and nicer than many fully functional archaeology labs where I've worked in the past.

Archaeological sites are places that contain material traces of human behavior. While the human behaviors that create archaeological sites are ultimately those of individuals, we usually can't resolve what we're looking at to that level. Traces of individual behaviors overprint one another and blend into a collective pattern. The granularity of individual behavior is usually lost.

Usually, but not always.

I spent portions of the last couple of works doing some preliminary excavation work at a site I first wrote about last October. Skipping over the details for now, documentation of an exposed profile measuring about 2.2 meters deep and 10 meters long showed the presence of cultural materials and intact features at several different depths. The portion of the deposits I am most interested in is what appears to be a buried zone of dark sediment, fire-cracked rock, and quartz knapping debris about 1.9 meters below the present ground surface. Based on the general pattern here in the Carolina Piedmont and a couple of projectile points recovered from the slump at the base of the profile, I'm guessing that buried cultural zone dates to the Middle Archaic period (i.e., about 8000-5000 years ago).

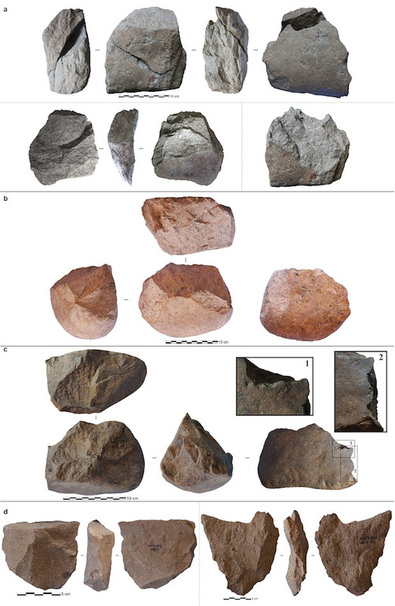

A buried assemblage of quartz chipping debris, probably created by a single individual during a single knapping episode.

A buried assemblage of quartz chipping debris, probably created by a single individual during a single knapping episode.  I did what I came to do.

I did what I came to do. Earlier in the month, I had the privilege of visiting the archaeological field schools being conducted at Topper. I wrote a little bit about the claim for a very early human presence at Topper here. The excavations associated with that claim aren't currently active. Field schools focused on Late Pleistocene/Early Holocene (Mississippi State University and the University of West Georgia) and Woodland/Mississippian (University of Tennessee) components at Topper and nearby sites have been running since early May. Seeing three concurrent field schools being run with the cooperation of personnel from four universities (and many volunteers) is remarkable.

Archaeologists love finding the earliest of anything and people love reading about it. While we often want to know how/when new things appear, identifying the "earliest of X" often gets play in the popular press that is disproportionate to its relevance to a substantive archaeological/anthropological question. And you can never really be sure, of course, that you've nailed down the earliest of anything: someone else could always find something earlier, falsifying whatever model was constructed to account for the existing information and moving the goal posts.

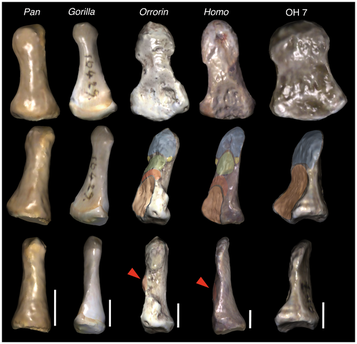

Exactly a year ago, I wrote about the reported discovery of 3.3 million-year-old stone tools from a site in Kenya. Those tools are significantly earlier than the previous "earliest" Oldowan tools. I think they're really interesting but not particularly surprising: several other lines of evidence (cut marks on bone, tool-use among chimpanzees, and hominin hand anatomy) already suggested that our ancestors were using tools well before the earliest Oldowan technologies appeared.

I anticipate that we still haven't seen the "earliest" stone tool use.

A recent report from India argues that our ideas about the "earliest" humans outside of Africa also miss the mark. (Note: when I say "human" I'm referring not to "modern human" but to a member of the genus Homo.) This story from March discusses a report of stone tools and cutmarked bone from India purportedly dating to 2.6 million-years-ago (MYA), blowing away the current earliest accepted evidence of humans outside of Africa (Dmanisi at 1.8 MYA) by about 800,000 years. With an increasing number of Oldowan assemblages dating to about 1.8-1.6 MYA are being reported outside of Africa (e.g., in China and Pakistan), would it be that surprising to find evidence a migration pre-dating 1.8 MYA? Probably not. Do the finds reported from India cement the case for human populations in South Asia at 2.6 MYA? Not yet: the fossils and tools reported from India so far (as far as I know anyway) don't have a context that allows them to be convincingly dated.

Forbidden Archaeology (ANTH 291-002): It's going to worthwhile.

Forbidden Archaeology (ANTH 291-002): It's going to worthwhile.

RSS Feed

RSS Feed