Yes, I just said that with a straight face. And yet I'm a surprisingly poor poker player.

| Over the last few days, I’ve travelled by car, air, and then car again to get from South Carolina to northern Georgia, Georgia to central Indiana (that was the air leg), then central Indiana to southeast Michigan. The purpose of the trip is to see family over the Thanksgiving break. But it also served up a reminder of the nature of seasonal differences in environment across the Eastern Woodlands. As a recent transplant from the Midwest to South Carolina, my seasonal clock is still adjusting: how can the semester be coming to a close when I’m still gardening in a short sleeve shirt? Seeing my breath on the jetway after landing in Indianapolis nudged my seasonal clock forward; the drive north to an Ann Arbor blanketed in snow finished off the reboot. The quick transplantation back to Ann Arbor made me ponder how hunter-gatherer societies would have handled regions of the Eastern Woodlands with such contrasts in the character, severity, and potential suddenness of seasonal changes. Just as Midwesterners today have to employ a set of behavioral and cultural strategies to deal with winter that is quite different from those necessary to survive the occasional day in Columbia when the temperature dips below freezing, there is no way that hunter-gatherers in the temperate Great Lakes could spend the winter doing the same things as hunter-gatherers in the sub-tropical Carolinas. This is not a profound idea, of course: hunter-gatherers have to deal with the characteristics of their environments in very direct ways, and whatever the particular social, cultural, and behavioral characteristics of a hunter-gatherer system, those characteristics have to allow the system to “fit” within its environment. Environment isn’t everything, but it’s important. |

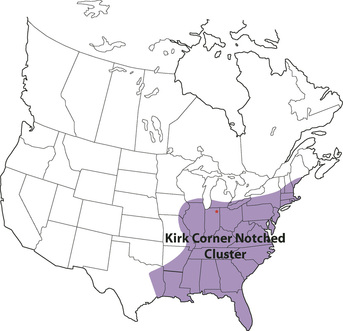

Distribution of Kirk Corner Notched cluster projectile points (adapted from Justice 1987).

Distribution of Kirk Corner Notched cluster projectile points (adapted from Justice 1987). But that doesn't mean they weren't part of the same society. We can define a "society" as a population defined by the existence of social ties among and between groups and individuals. Ethnographic hunter-gatherers have numerous mechanisms for creating and maintaining social ties (e.g., marriage, exchange, group flux, periodic aggregation), and there is no reason to suspect that all of those same behaviors were not utilized to knit together the social fabric of early Holocene hunter-gatherers in the Eastern Woodlands. Maintaining social ties that extend beyond "over the horizon" may be especially important to high mobility hunter-gatherers operating at low population densities, as such ties allow local populations to gather information about large areas of the landscape.

A couple of Kirk cluster points from northwest Indiana.

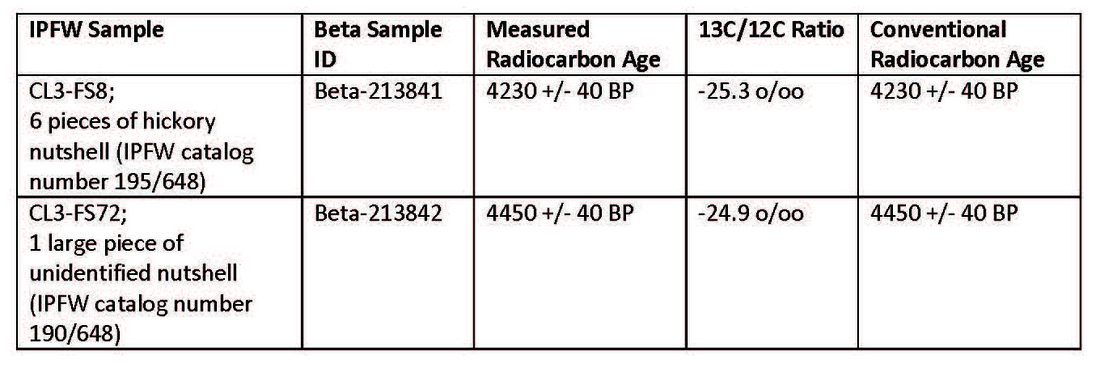

A couple of Kirk cluster points from northwest Indiana. First, you need data that actually let you characterize the degree of variability in the Kirk Corner Notched cluster and how that variability breaks down with regard to space (and raw material use). Given how widespread Kirk is, that's a big job. But it's a doable job with the right commitment: Kirk points are common and fairly easy to recognize (they really are remarkably similar in different parts of the east, at least the ones I've looked at). I started working on assembling a Kirk dataset from the Midwest as part of my dissertation work and grant work while I was at IPFW. I'm going to continue that work down south: I've applied for some grant money to start working on inventorying and collecting data from a large collection of points from Allendale County, South Carolina, and there are numerous other existing collections available. My plan is to create 3D models of the points as I analyze them, which will aid in both morphometric analysis and data sharing. I don't think I'll have to create the whole Kirk database myself (see this post about 3D modeling of points from the Hardaway site in North Carolina).

Second, it's a modeling problem. How much interaction across a social landscape the size of the eastern United States would be required to produce and maintain the degree of stylistic uniformity that we see? You can't answer that without a model that lets you understand how patterns of social interaction might affect patterns of artifact variability (run-of-the-mill equation-based cultural transmission models won't cut it, either, because they typically don't take spatially-structured interaction into account). I started to try to tackle that question in my dissertation and with some other modeling work. The simple assumption that the degree of homogeneity would be proportional to the degree of interaction is probably wrong: network theory suggests to me that a nonlinear relationship is more likely (a small degree of interaction can produce a large degree of homogeneity).

Significant differences in the density and behaviors of deer populations would have had implications for the hunter-gatherer populations that exploited them, perhaps especially during the Fall and Winter. I would guess that variability in deer populations and behavior vary continuously across the Eastern Woodlands along with other aspects of environment (temperature, mast production, etc.). Different strategies, perhaps involving patterns of seasonal mobility and aggregation, would have surely been required in the far north and far south of the region. Whatever the components of those differences, however, they were apparently not sufficient to produce hunter-gatherer societies that were disconnected on the macro level during the Early Archaic period. It may be the case, in fact, that differences in seasonality across the region, in a context of low population densities, actually encouraged rather than discouraged the creation of an "open" social network that resulted in the emergence of the Kirk Horizon. Later on in the Archaic we do indeed see a regionalization of material culture that makes the Midwest look different from the Southeast.

Whatever the characteristics of their larger social networks (and smaller social units within those networks), those Early Archaic societies provided a foundation for much of the Eastern Woodlands prehistory that follows. It's going to require theory-building and a lot of data from a large area to understand it. We need some kind of Kirk Manhattan Project.

RSS Feed

RSS Feed