Sexual selection is selection (differential reproduction) that occurs when some individuals reproduce more than others because they are better at securing mates, rather than because of interaction with the environment (as in natural selection. Charles Darwin coined the term and explained in On the Origin of Species (1859:88). Sexual selection, he wrote,

"depends, not on a struggle for existence, but on a struggle between the males for possession of the females; the result is not death to the unsuccessful competitor, but few or no offspring. Sexual selection is, therefore, less rigorous than natural selection. Generally, the most vigorous males, those which are best fitted for their places in nature, will leave most progeny. But in many cases, victory will depend not on general vigour, but on having special weapons, confined to the male sex. . . . The war is, perhaps, severest between the males of polygamous animals, and these seem oftenest provided with special weapons."

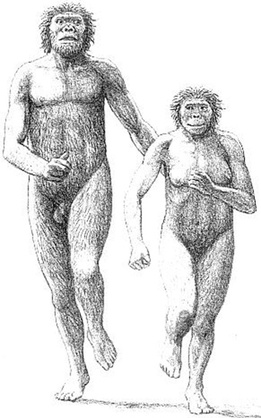

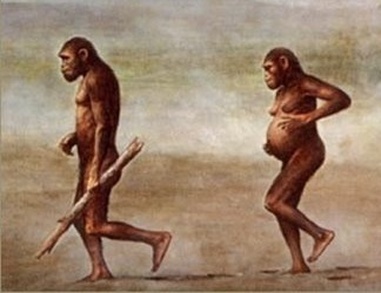

How important was sexual selection among australopithecines? We have traditionally looked at two aspects of sexual dimorphism (differences between males and females) to evaluate the degree of male-male competition in primates: canine size and body size. If sexual selection was important among australopithecines (as it is chimpanzees and gorillas, our two closest living relatives) we would expect to see males with significantly larger canines and of significantly greater body size than females. The fossil record isn't as clear on these things as you might think.

Canine Size

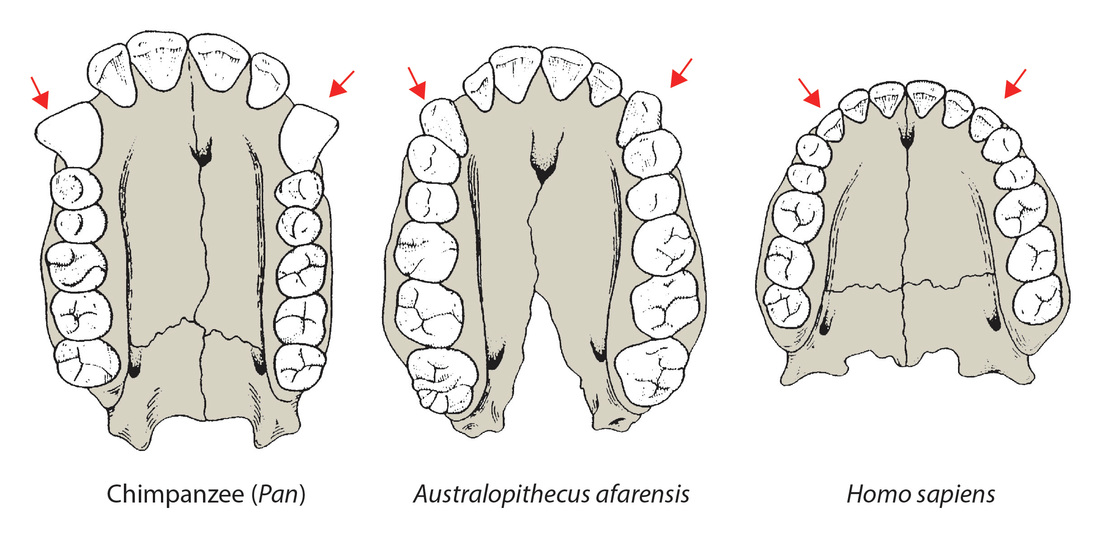

The drawing below shows maxillary dentitions from a chimpanzee, an Australopithecus afarensis (ca. 3.9-2.9 MYA), and a modern human. I think the original drawing is from the (1981) book Lucy: The Beginnings of Humankind by Donald Johanson and Maitland Edey. The difference in the relative sizes of the canines (indicated with red arrows) is obvious. Chimpanzees (especially males) have large canines. The space between the canine and the incisors (called a diastema) is there to accommodate the opposing canine when the jaws are closed. The canines of modern humans barely protrude at all, and there is no diastema. The canines of australopithecines are larger than those of modern humans, but smaller than those of chimps. They protrude slightly, and there is a small diastema.

"Estimates of canine dimorphism, relative canine size, and body weight dimorphism in australopithecines provide little definitive information about male–male competition or mating systems. Dimorphism of Australopithecus africanus and Australopithecus robustus can be reconciled with a mating system characterized by low-intensity male–male competition. The pattern of dimorphism and relative canine size in Australopithecus afarensis and A. robustus provides contradictory evidence about mating systems and male–male competition."

This 2005 paper by Sang-Hee Lee paper concluded (based on a resampling method that wasn't dependent on sex estimates) that canine sexual dimorphism in Australopithecus afarensis was comparable to that seen in chimpanzees.

The canines of Ardipithecus ramidus (ca. 4.4 MYA) are smaller than those of chimpanzees but larger than those of modern humans. The image below shows a comparison of a modern human (left), Ardipithecus (middle), and chimpanzee (right) (source). The teeth in the image belong to "Ardi," the relatively complete skeleton of Ardipithecus ramidus discovered in 1994 and published in 2009. That skeleton has been interpreted as the remains of a female. An analysis of other Aridipithecus ramidus teeth (Suwa et al. 2009) concluded that male and female canine teeth were of similar size.

The single published skull from Sahelanthropus, a possible hominid from about 7 MYA, has been interpreted as that of a male with a relatively small canine. I don't claim to have read the Sahelanthropus studies in detail, but I'm dubious that you can accurately estimate sex for a single skull from species about which so little else is known. If the skull is that of a male, whether or not it's a hominid, it would be consistent with a low level of sexual selection in late Miocene apes. If it's a female it doesn't tell us much about competition between males.

So the canine picture is a confusing one. The canines of australopithecines sure don't look large to me (compared to chimpanzees), but at least some studies suggest a relatively high degree of dimorphism among some australopithecines. If either Ardipithecus or Sahelanthropus was a hominid with a low degree of sexual dimorphism of the canines (suggesting low male-male competition), greater canine sexual dimorphism among australopithecines would suggest an increase in sexual selection during the Pliocene. If the LCA was more like a chimpanzee, however, sexual selection may have decreased during the Pliocene.

Body Size

The body size picture is also confusing. You can find a paper to support whatever you want, from a high degree of sexual dimorphism in body size (like gorillas) to a low degree of sexual dimorphism (like modern humans). When I talk to my Human Origins class about it, I just tell them what sexual dimorphism is and why we would like to know about it, and then confess that I can't make up my mind what the best answer is at the moment.

A paper published last week came down on the side of low sexual dimorphism in body size. The authors, Philip Reno and Owen Lovejoy, conclude that:

"The relatively stable size patterns observed between Ardipithecus and Australopithecus suggest there was not strong selection for greater male body size that would result from a reproductive strategy arising from increased individual male reproductive success via inter-individual aggression. In fact, the reduction in canine dimorphism with feminization in the male would argue for reduced “agonistic” behaviors (Lovejoy, 2009). This is particularly so given the strong association between canine dimorphism and reproductive behavior in anthropoids (Plavcan, 2012b) and the lack of a dramatic dietary shift associated with canine modification in early hominids (Suwa et al., 2009)."

This is not a new argument from Lovejoy, who has been hypothesizing the presence of monogamous reproductive strategies among early hominids for decades.

We've got a lot to learn about australopithecine social organization and the lack of clarity about sexual dimorphism does not help. In my post about whether birth assistance was a gendered activity, I reasoned that it would be more likely that males would be involved in birth assistance if males and females were pair-bonded. In that circumstance, paternity would be more-or-less certain, and male behavior that increased the success of reproduction would be selected for. Overall, I like the anatomical evidence for a relatively low level of sexual selection among australopithecines, consistent with low levels of male-male competition. Without being able to accurately determine the sex of australopithecine fossils, however, its hard to have a lot of confidence. If Lovejoy is right about Ardipithecus, male-female pair-bonding was already present in the ancestors of australopithecines (could it even have been typical of many apes in the late Miocene?). If the LCA was more like a chimpanzee, however, sexual selection may have been strong at the time of the divergence of the chimpanzee and human lineages.

Even if australopithecines had a monogamous, pair-bonded mating system, however, that doesn't mean there was anything like culture attached to it. It may have just been part of a hard-wired biological adaptation, one that emerged along with bipedalism because it made evolutionary sense. Along with certainty of paternity would come greater paternal investment in offspring, presumably resulting in a higher survival rate (hence being selected for). The low/moderate amounts of sexual dimorphism in body size could be accounted for by the positive relationship between body size and energy efficiency during bipedal locomotion: males provisioning females and their offspring would have to travel longer distances than females, selecting for larger body sizes among males (but not larger canines) (see Daniel Lieberman's book The Story of the Human Body). In this scenario, "love" would be related to sexual dimorphism not because of male-male competition but because bigger males would be better providers.

Convinced? I'm not (either way). But it's worth thinking about.

RSS Feed

RSS Feed