Eastern Woodlands Prehistory

The Eastern Woodlands of North America has a lot going for it as a place to do research. It's big, full of interesting archaeology supported by a long history of investigation by a lot of archaeologists, and has an abundance of cheap motels and places to get fast food. Say what you want about Motel 6 and McDonald's, but they were of such critical importance to the completion of my dissertation that I probably should have put a line in the acknowledgements.

In general terms, the Eastern Woodlands can be defined as the geographic area bordered by the Atlantic Ocean to the east, the Gulf of Mexico to the south, the Great Plains to the west, and the Subarctic to the north. This is a large area that encompasses a lot of diversity in terms of weather, topography, and biota. The Eastern Woodlands as a whole, however, is united by several environmental characteristics that make it distinct from the surrounding regions: a temperate climate, abundant rain, and lots of trees. The importance of these commonalities of environment to historic Native American peoples was evident to Alfred Kroeber when he was preparing his map of the cultural-geographical areas of North America (shown to the right, image from here). The Eastern Woodlands basically encompasses Kroeber's Northeast and Southeast regions.

It is evident that the Eastern Woodlands was a cohesive “culture area” throughout much of prehistory. Material cultures of the east and west became distinct early in North American prehistory as the pan-continental Clovis phenomenon gave way to regionalized projectile point forms during the Pleistocene-Holocene transition (beginning perhaps about 10,700 BC). This was a messy process and one we don’t yet fully understand (I’ve written a little bit about it in this 2006 paper and in my dissertation). Following the emergence of forest environments in the east that are more-or-less like those of today, spatial cohesion and temporal continuity among the prehistoric societies of the Eastern Woodlands is clear throughout prehistory.

Numerous fascinating and inter-connected stories played out during the thirteen thousand years of Eastern Woodlands prehistory: populations grew larger, societies became more densely packed, languages diversified, the production and storage of food intensified, institutionalized inequalities emerged, and chiefdoms rose and fell. We know that a similar suite of stories played out in other parts of the world at other times. And we also know that there is significant variability in the plot lines of those stories: no two cases are identical in terms of their timing, conditions, and outcomes. Even within the Eastern Woodlands these stories did not unfold uniformly over time and space.

These similarities and differences are telling us something important. The presence of broad patterns of change in world prehistory demonstrates that common processes underlie changes in human societies. The presence of case-by-case differences, in contrast, demonstrates that the storylines that arc through prehistory are not inevitable: the beginnings matter, the actors matter, and the plot matters. I am interested in understanding how we explain both the similarities and differences. What are the common underlying processes that fuel or constrain long-term change? What effects do conditions of the environment (whether social or physical) exert? What active roles can the most basic constituent parts of societies – individuals and households – play in these stories?

These are anthropological questions that, because they concern large scales of time and space, must be addressed with archaeological data. They are also questions which can be approached with complexity science in a much more ambitious and credible way than is otherwise possible. They are perfect questions for anthropological, model-based archaeology in the Eastern Woodlands. In the following sections, I will touch on the strengths of the archaeological record of this region and discuss one of the key stories I am interested in: the emergence of social complexity.

In general terms, the Eastern Woodlands can be defined as the geographic area bordered by the Atlantic Ocean to the east, the Gulf of Mexico to the south, the Great Plains to the west, and the Subarctic to the north. This is a large area that encompasses a lot of diversity in terms of weather, topography, and biota. The Eastern Woodlands as a whole, however, is united by several environmental characteristics that make it distinct from the surrounding regions: a temperate climate, abundant rain, and lots of trees. The importance of these commonalities of environment to historic Native American peoples was evident to Alfred Kroeber when he was preparing his map of the cultural-geographical areas of North America (shown to the right, image from here). The Eastern Woodlands basically encompasses Kroeber's Northeast and Southeast regions.

It is evident that the Eastern Woodlands was a cohesive “culture area” throughout much of prehistory. Material cultures of the east and west became distinct early in North American prehistory as the pan-continental Clovis phenomenon gave way to regionalized projectile point forms during the Pleistocene-Holocene transition (beginning perhaps about 10,700 BC). This was a messy process and one we don’t yet fully understand (I’ve written a little bit about it in this 2006 paper and in my dissertation). Following the emergence of forest environments in the east that are more-or-less like those of today, spatial cohesion and temporal continuity among the prehistoric societies of the Eastern Woodlands is clear throughout prehistory.

Numerous fascinating and inter-connected stories played out during the thirteen thousand years of Eastern Woodlands prehistory: populations grew larger, societies became more densely packed, languages diversified, the production and storage of food intensified, institutionalized inequalities emerged, and chiefdoms rose and fell. We know that a similar suite of stories played out in other parts of the world at other times. And we also know that there is significant variability in the plot lines of those stories: no two cases are identical in terms of their timing, conditions, and outcomes. Even within the Eastern Woodlands these stories did not unfold uniformly over time and space.

These similarities and differences are telling us something important. The presence of broad patterns of change in world prehistory demonstrates that common processes underlie changes in human societies. The presence of case-by-case differences, in contrast, demonstrates that the storylines that arc through prehistory are not inevitable: the beginnings matter, the actors matter, and the plot matters. I am interested in understanding how we explain both the similarities and differences. What are the common underlying processes that fuel or constrain long-term change? What effects do conditions of the environment (whether social or physical) exert? What active roles can the most basic constituent parts of societies – individuals and households – play in these stories?

These are anthropological questions that, because they concern large scales of time and space, must be addressed with archaeological data. They are also questions which can be approached with complexity science in a much more ambitious and credible way than is otherwise possible. They are perfect questions for anthropological, model-based archaeology in the Eastern Woodlands. In the following sections, I will touch on the strengths of the archaeological record of this region and discuss one of the key stories I am interested in: the emergence of social complexity.

Barns and Lime Jell-O

At one point during my doctoral work (I think it was during the Paleoindian workshop I discussed here), a very smart archaeologist whom I respect a great deal cautioned me to resist the pull of exotic places and stay and work in the Midwest. “Sure,” he said, “Europe has the Adriatic and we just have barns and lime Jell-O, but there’s more to it than that.”

Of course he was right, and, as you might guess, he was preaching to the choir. Eastern North America has a number of strengths in terms of its suitability for conducting research on “big” anthropological and archaeological questions. Two are at the top of the list:

Interesting things happened. My favorite description of what constitutes a story (attributed to Joseph Campbell by Edward Norton in this interview) is that “something happens and as a result something changes.” The prehistory of the Eastern Woodlands is filled with stories large and small: things happened here, and things changed as a result.

We have data. We have collected a tremendous amount of archaeological data over the last century or so. This information, much of it from CRM projects, provides a solid foundation upon which to base investigations of the stories of Eastern Woodlands prehistory. While these archaeological data alone do not tell stories, they do provide an essential empirical basis for developing and evaluating our stories.

In many ways, the second strength (the presence of data) is more important than the first. I would guess that interesting things happened in most places in the world where human societies have existed. Humans and human societies are not boring: we have made a collective career out of being interesting. But dense archaeological data that give us a material record about those interesting things we've done is most certainly not available everywhere. I could not even begin to guess how many person-hours and billions of dollars have gone into archaeological work in eastern North America in the last 100 years. That work has provided us with a wealth of information about what happened here over the last thirteen thousand years. That's a great thing to have. (An aside: much of this information, I would argue, is being significantly under-utilized. We are handicapping ourselves by not more effectively capitalizing on the potential of the information we already have. We’re in the Millennium Falcon but the hyperdrive is disabled – we should really look into getting that fixed. That's why I support the DINAA project and am an advocate for the benefits of linked data.)

Finally, I will state for the record that neither barns nor lime Jell-O are bad things. If pressed on this point by someone who works someplace "better," I tend to get a little annoyed. I would much rather eat lime Jell-O in a barn than spend my career pretending to address big questions while actually being compelled to focus my energies on figuring out the most basic aspects of chronology because I chose to work in an archaeological black hole that has really nice palm trees and more exciting food. Don't get me wrong: I like palm trees, too. And I like exciting food. But I like the choice I made to maintain my research focus in the land of barns and lime Jell-O. It's a good place to be for what interests me.

At one point during my doctoral work (I think it was during the Paleoindian workshop I discussed here), a very smart archaeologist whom I respect a great deal cautioned me to resist the pull of exotic places and stay and work in the Midwest. “Sure,” he said, “Europe has the Adriatic and we just have barns and lime Jell-O, but there’s more to it than that.”

Of course he was right, and, as you might guess, he was preaching to the choir. Eastern North America has a number of strengths in terms of its suitability for conducting research on “big” anthropological and archaeological questions. Two are at the top of the list:

Interesting things happened. My favorite description of what constitutes a story (attributed to Joseph Campbell by Edward Norton in this interview) is that “something happens and as a result something changes.” The prehistory of the Eastern Woodlands is filled with stories large and small: things happened here, and things changed as a result.

We have data. We have collected a tremendous amount of archaeological data over the last century or so. This information, much of it from CRM projects, provides a solid foundation upon which to base investigations of the stories of Eastern Woodlands prehistory. While these archaeological data alone do not tell stories, they do provide an essential empirical basis for developing and evaluating our stories.

In many ways, the second strength (the presence of data) is more important than the first. I would guess that interesting things happened in most places in the world where human societies have existed. Humans and human societies are not boring: we have made a collective career out of being interesting. But dense archaeological data that give us a material record about those interesting things we've done is most certainly not available everywhere. I could not even begin to guess how many person-hours and billions of dollars have gone into archaeological work in eastern North America in the last 100 years. That work has provided us with a wealth of information about what happened here over the last thirteen thousand years. That's a great thing to have. (An aside: much of this information, I would argue, is being significantly under-utilized. We are handicapping ourselves by not more effectively capitalizing on the potential of the information we already have. We’re in the Millennium Falcon but the hyperdrive is disabled – we should really look into getting that fixed. That's why I support the DINAA project and am an advocate for the benefits of linked data.)

Finally, I will state for the record that neither barns nor lime Jell-O are bad things. If pressed on this point by someone who works someplace "better," I tend to get a little annoyed. I would much rather eat lime Jell-O in a barn than spend my career pretending to address big questions while actually being compelled to focus my energies on figuring out the most basic aspects of chronology because I chose to work in an archaeological black hole that has really nice palm trees and more exciting food. Don't get me wrong: I like palm trees, too. And I like exciting food. But I like the choice I made to maintain my research focus in the land of barns and lime Jell-O. It's a good place to be for what interests me.

The Emergence of Social Complexity: A Story Worth Understanding

How, why, and under what circumstances ‘‘simple’’ human cultural systems transform into ‘‘complex’’ ones is a fundamental topic of anthropological interest. Where do differentials in wealth and power within societies come from? How are they maintained? How do inequalities become institutionalized in societies with strong leveling mechanisms? These are questions of profound significance for understanding how, why, and in what ways human societies change.

How, why, and under what circumstances ‘‘simple’’ human cultural systems transform into ‘‘complex’’ ones is a fundamental topic of anthropological interest. Where do differentials in wealth and power within societies come from? How are they maintained? How do inequalities become institutionalized in societies with strong leveling mechanisms? These are questions of profound significance for understanding how, why, and in what ways human societies change.

|

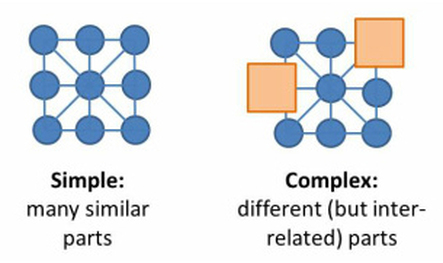

First, some clarification about what I mean by “social complexity.” In general terms, something that is “simple” has parts that are equivalent, while something that is “complex” has parts that are not equivalent. The constituent, inter-connected parts of a simple social system are equivalent to one another. A complex social system, in contrast, has interconnected parts that are not equivalent.

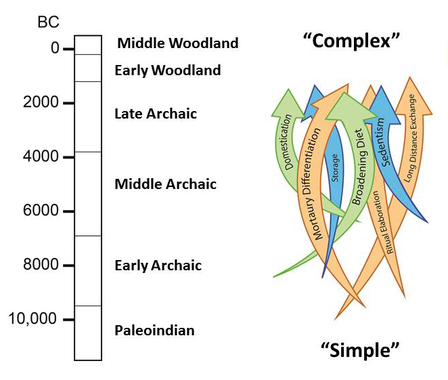

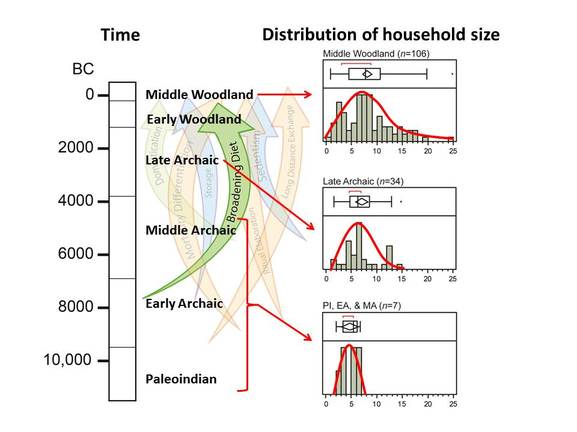

When we’re talking about hunter-gatherer societies, the constituent parts that we’re most interested in are individuals and families: these are the fundamental, decision-making units that link together into a social system. It is the family/household, rather than the individual, that is most important in understanding the emergence and ossification of social inequalities. Inequalities among individuals (based on age, sex, personal abilities, etc.) are present in all ethnographic hunter-gatherer societies. In “egalitarian” societies, the personal status differentiations associated with those inequalities disappear along with the person. A qualitatively different situation exists when there are mechanisms for ascribing status based on family membership. The inheritance of status fundamentally changes how societies work because it breaks the symmetry among the parts in a way that can persist through generations. When this happens, inequality has become institutionalized. In the Eastern Woodlands, a transformation from “simple” to “complex” societies took place over the course of eight to ten thousand years. Hunter-gatherer societies of the Early Archaic period (ca. 9500-6900 BC) were highly mobile, completely dependent on wild foods, and had none of the organizational characteristics of social complexity. By the Middle Woodland period (ca. 200 BC-AD 500), eastern North America was populated with semi-sedentary, food-producing societies engaged in elaborate ritual, mortuary, and exchange behaviors. Some degree of social ranking was important to how these Middle Woodland societies operated, and there is evidence of status differentiation among clans or lineages in some areas. The “simple to complex” transformation involved inter-woven threads of demographic change, subsistence intensification, plant domestication, elaboration of exchange and mortuary behaviors, and changes in settlement pattern. |

The profound set of inter-related economic, social, political, and organizational changes that took place in the Eastern Woodlands (and also elsewhere in the world) has been the subject of debate for decades. While explanations of these changes often include a discussion of changes in family size, composition, autonomy, and wealth, I find them generally unsatisfying. The main reason is that they do not adequately describe and demonstrate the links between the day-to-day and year-to-year behaviors and decisions of individuals and families at the operational level and the long-term evolutionary changes we see in these societies (see the complexity science section for a brief discussion of these levels). This is not a trivial issue: failure to link these two levels significantly weakens our explanations of change as it leaves intentional human behaviors essentially uncoupled from social change.

I think we can do better. We can improve our understanding of the emergence of social complexity in the Eastern Woodlands by taking a long-term approach that considers the societies upon which processes of change operated, puts the behaviors of families/households in the analytical foreground, uses agent-based modelling to link those behaviors to system-level change and archaeological expectations, and utilizes archaeological data at scales that match those of the systems we are trying to understand. Ambitious? You bet. Easy? No. Doable? Absolutely – maybe more-so in the Eastern Woodlands than anywhere else in the world.

I think we can do better. We can improve our understanding of the emergence of social complexity in the Eastern Woodlands by taking a long-term approach that considers the societies upon which processes of change operated, puts the behaviors of families/households in the analytical foreground, uses agent-based modelling to link those behaviors to system-level change and archaeological expectations, and utilizes archaeological data at scales that match those of the systems we are trying to understand. Ambitious? You bet. Easy? No. Doable? Absolutely – maybe more-so in the Eastern Woodlands than anywhere else in the world.

A Recipe

A process is a recipe: it transforms a set of ingredients (inputs) into and end product (an output). Let’s say we’re making scrambled eggs. The end product is a result of the ingredients we use, the recipe we follow, and the particular way we execute the recipe. We can’t get scrambled eggs by cooking bacon (inputs). We can’t get scrambled eggs by putting the eggs in the freezer rather than applying heat (process). The eggs may taste different depending on if they were cooked with butter, or fried in an iron skillet, or seasoned with pepper (history). The input matters, process matters, and history (that which could have been different) matters to the outcome.

The same is true of prehistory. I do not think we can construct satisfying explanations of complex, long-term prehistoric changes without accounting for all three. I'm going to briefly describe three aspects of what I think is an approach to the emergence of social complexity in the Eastern Woodlands that has the potential to help us understand what happened, how it happened, and why it happened:

Early foraging societies. You cannot address a question of long-term change by focusing only on the end result. We know quite a bit about the Middle Woodland period, especially the spectacular remains associated with the Hopewell “zenith.” These societies are the result of thousands of years of change that began early in the prehistory of eastern North America. To understand the story of how those societies came to be you have to start at the very beginning. It is, after all, a very good place to start.

The Paleoindian and Early Archaic societies of the Eastern Woodlands are the inputs of the story. Understanding these societies is not easy: in many cases our empirical data are limited to stone tools distributed across the landscape. While we have managed to make some pretty interesting observations based on those tools and some associated sites, it is difficult to confidently describe those societies using only the very light footprint they left on the landscape. My doctoral work used a complex systems approach to try to generate insights about how the social systems of these Late Pleistocene and Early Holocene hunter-gatherers were wired together. This was an attempt to begin building an analytically-sound description of the “initial conditions” upon which long-term processes of change begin to operate.

The austere nature of the Paleoindian and Early Archaic records convinced me that we need to put some effort into developing more ways to wring insights about social phenomena from technological artifacts. The first logical step in doing this is to build a reasonable “null model” that provides some basic expectations for how, why, and in what ways technologies change. I took some steps toward this goal in my 2008 World Archaeology paper and in my dissertation. My 2013 JASSS modeling paper also contributes to this goal.

A process is a recipe: it transforms a set of ingredients (inputs) into and end product (an output). Let’s say we’re making scrambled eggs. The end product is a result of the ingredients we use, the recipe we follow, and the particular way we execute the recipe. We can’t get scrambled eggs by cooking bacon (inputs). We can’t get scrambled eggs by putting the eggs in the freezer rather than applying heat (process). The eggs may taste different depending on if they were cooked with butter, or fried in an iron skillet, or seasoned with pepper (history). The input matters, process matters, and history (that which could have been different) matters to the outcome.

The same is true of prehistory. I do not think we can construct satisfying explanations of complex, long-term prehistoric changes without accounting for all three. I'm going to briefly describe three aspects of what I think is an approach to the emergence of social complexity in the Eastern Woodlands that has the potential to help us understand what happened, how it happened, and why it happened:

- building an understanding of early foraging societies

- building an understanding of intensification and demographic packing

- linking household-level behaviors to system-level changes

Early foraging societies. You cannot address a question of long-term change by focusing only on the end result. We know quite a bit about the Middle Woodland period, especially the spectacular remains associated with the Hopewell “zenith.” These societies are the result of thousands of years of change that began early in the prehistory of eastern North America. To understand the story of how those societies came to be you have to start at the very beginning. It is, after all, a very good place to start.

The Paleoindian and Early Archaic societies of the Eastern Woodlands are the inputs of the story. Understanding these societies is not easy: in many cases our empirical data are limited to stone tools distributed across the landscape. While we have managed to make some pretty interesting observations based on those tools and some associated sites, it is difficult to confidently describe those societies using only the very light footprint they left on the landscape. My doctoral work used a complex systems approach to try to generate insights about how the social systems of these Late Pleistocene and Early Holocene hunter-gatherers were wired together. This was an attempt to begin building an analytically-sound description of the “initial conditions” upon which long-term processes of change begin to operate.

The austere nature of the Paleoindian and Early Archaic records convinced me that we need to put some effort into developing more ways to wring insights about social phenomena from technological artifacts. The first logical step in doing this is to build a reasonable “null model” that provides some basic expectations for how, why, and in what ways technologies change. I took some steps toward this goal in my 2008 World Archaeology paper and in my dissertation. My 2013 JASSS modeling paper also contributes to this goal.

Intensification and demographic packing. What happens as hunter-gatherer populations grow in size and density? A lot of things. In eastern North America during the Middle and Late Archaic periods (ca. 7000-1500 BC), long term increases in population size and density generally seem to be accompanied by ongoing trends of increasing sedentism, reduced scales of mobility, amplification of extra-local exchange, regionalization of material culture, and broadening of diets. These changes would have had effects and implications both at the level of the social system and the level of the families/households that act, react, and interact within that system.

Archaeologists have thought a lot about intensification and demographic packing, both in terms of general theory and particular archaeological cases, including the Eastern Woodlands. The large number of inter-related changes and feedbacks that reverberate across time and space make determining cause and effect really tricky: this a seriously thorny set of problems. While considering the available ethnographic data (from many contemporaneous societies scattered across the globe) is useful for generating insights into how these variables are inter-related in living systems, it only gets you part of the way toward explaining a sequence of changes that we can identify archaeologically. Lewis Binford’s last major work, Frames of Reference, shows this: in my opinion, it is as convincing a demonstration as any that ethnographic data alone can never reveal how systems change over the long-term.

I’m going to guess that you correctly anticipated what I’m going to say next: a complex systems approach offers a way forward through the entanglement of intensification that logical model building and ethnographic comparisons can never provide. Agent-based models can be used to represent the articulations between the levels in a social system, build theory about the inter-relationships between changes in those levels, and produce outputs that can be compared to archaeological sequences of change. The language of complexity science is all over Frames of Reference, but, unfortunately, the methods are not. Complexity science is the direction we need to go.

The archaeological record of the Middle and Late Archaic periods includes several classes of remains that will be really useful in this endeavor. We have a lot of substantial sites dating to these time periods. Some of these sites include residential structures, features and artifacts for processing, storing, and disposing of food remains, and mortuary remains. This last class of remains is particularly important: mortuary remains potentially provide us with direct information about demography, health, activity patterns, mating patterns, and dimensions of status differentiation. A well-designed ABM could provide outputs that could be compared to all of these aspects of archaeological record. I’m especially interested in using ABMs as tools for paleodemography (see this paper) because, unlike many traditional paleodemographic methods, one does not have to make the assumption of stable population size to arrive at interpretations of fertility and mortality rates. Considering that population growth appears to be one of the dominant, ongoing trends of the Archaic, it seems a bit silly to rely on analytical techniques that require you to assume zero population growth when there are other options available.

Archaeologists have thought a lot about intensification and demographic packing, both in terms of general theory and particular archaeological cases, including the Eastern Woodlands. The large number of inter-related changes and feedbacks that reverberate across time and space make determining cause and effect really tricky: this a seriously thorny set of problems. While considering the available ethnographic data (from many contemporaneous societies scattered across the globe) is useful for generating insights into how these variables are inter-related in living systems, it only gets you part of the way toward explaining a sequence of changes that we can identify archaeologically. Lewis Binford’s last major work, Frames of Reference, shows this: in my opinion, it is as convincing a demonstration as any that ethnographic data alone can never reveal how systems change over the long-term.

I’m going to guess that you correctly anticipated what I’m going to say next: a complex systems approach offers a way forward through the entanglement of intensification that logical model building and ethnographic comparisons can never provide. Agent-based models can be used to represent the articulations between the levels in a social system, build theory about the inter-relationships between changes in those levels, and produce outputs that can be compared to archaeological sequences of change. The language of complexity science is all over Frames of Reference, but, unfortunately, the methods are not. Complexity science is the direction we need to go.

The archaeological record of the Middle and Late Archaic periods includes several classes of remains that will be really useful in this endeavor. We have a lot of substantial sites dating to these time periods. Some of these sites include residential structures, features and artifacts for processing, storing, and disposing of food remains, and mortuary remains. This last class of remains is particularly important: mortuary remains potentially provide us with direct information about demography, health, activity patterns, mating patterns, and dimensions of status differentiation. A well-designed ABM could provide outputs that could be compared to all of these aspects of archaeological record. I’m especially interested in using ABMs as tools for paleodemography (see this paper) because, unlike many traditional paleodemographic methods, one does not have to make the assumption of stable population size to arrive at interpretations of fertility and mortality rates. Considering that population growth appears to be one of the dominant, ongoing trends of the Archaic, it seems a bit silly to rely on analytical techniques that require you to assume zero population growth when there are other options available.

|

Families, systems, and change. The family/household is at the nexus of social, political, and economic life in hunter-gatherer societies: it is within these “minimal” social units that people act and react to their circumstances and make decisions based on their own local, limited information. This is where the action is. How do day-to-day, week-to-week, and year-to-year actions and interactions of households translate into millennial-scale changes in societies and cultures?

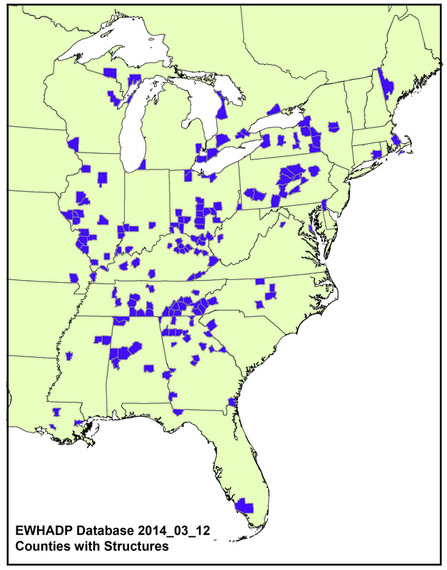

This is a difficult question. It may actually be the question. We need to have a couple of things to start to answer it. First, we need to have models that are capable of helping us understand how changes in the operational processes of households are linked to long-term , large-scale evolutionary changes that unfold at the system level. Second, we need to have archaeological data that we can compare to the outputs of those models. This includes data relevant to describing aspects of both systems and households. Let’s talk about the empirical data first. The most direct source of empirical data about the size, composition, and activities of prehistoric households is the remains of houses. It is in the archaeology of residential structures that we expect patterned changes in within- and between-household social relations to be most visible. To understand how patterns change, however, we need more than one house here or there. We need as many as possible: the more the better. Paleoindian residential structures are almost unknown in eastern North America. Archaic and Woodland residential structures, while not common, are more plentiful than you might guess. I assembled information on hundreds for this paper in the Journal of Anthropological Archaeology. Assembling that information was time consuming, as much of it was to be found in the so-called grey literature of CRM, theses, and dissertations. I pulled together a decent sample, but I’m sure there is much more information out there that can be assembled and built upon (that’s why I started the Eastern Woodlands Household Archaeology Data Project). My analysis in the JAA paper suggested that positive feedbacks between the productive and reproductive potentials of larger families, coincident with subsistence intensification, might have been an important factor in the emergence of heredity distinctions in social status. Basically, I suggested that subsistence intensification permitted much greater variation in family size. This variation in family size would have provided room for inequalities to germinate and eventually (with mechanisms for preserving wealth/status in lineages) ossify. The analysis in that paper was done with a broad brush – it was a start at using model-based analysis to derive expectations that we can compare to archaeological data. Moving forward we will need to incorporate finer analyses of household-level social relations. Among other things, I think we need to make a concerted effort to get at understanding changes in how gender structured social relations within and between households. Ethnographic data show (pretty unambiguously) that gender is a primary variable affecting how labor is organized and how the products of that labor are used in hunter-gatherer societies. Changes in subsistence, mobility, demography, and the social networks guiding exchange all would have articulated with the sexual division of labor at the household level. Gender is the elephant in the room of archaeological research on hunter-gatherers: we all know it’s huge but we do little to address it. |

At the other end of the scale, we’ll need archaeological data to characterize change in parameters of group mobility, the spatial extent of social systems, and the kinds and intensity of interactions within and between social systems. The challenge in collecting this kind of information is mainly one of scale: the cultural systems we're talking about operated across large areas of the landscape during long spans of time. Much of the data that one would need to frame changes at large scales is available from existing collections that are sitting in museums, county historical societies, and shoeboxes in someone’s closet. The data are out there: it is a matter of purposefully gathering them. Not an easy task, but do-able.

Agent-based modeling is a tool for linking the day-to-day, local-scale “operational” processes of the living social systems of hunter-gatherers to the “evolutionary” processes of change that unfolded in eastern North America and the archaeological patterns associated with those changes. Plausible sequences of change can be constructed by “tuning” the rules/conditions/parameters of the model until model systems produce changes in patterns that are consistent with those we can discern archaeologically, time period by time period. Use of multiple archaeological datasets – data on households, mobility, subsistence, demography, exchange -- provides several distinct points of comparison between both the “macro” and “micro” aspects of model social systems and archaeological data. Archaeological data are the direct evidence of what we’re trying to understand: in order for an explanation to be convincing, it needs to be concordant with that evidence.

Agent-based modeling is a tool for linking the day-to-day, local-scale “operational” processes of the living social systems of hunter-gatherers to the “evolutionary” processes of change that unfolded in eastern North America and the archaeological patterns associated with those changes. Plausible sequences of change can be constructed by “tuning” the rules/conditions/parameters of the model until model systems produce changes in patterns that are consistent with those we can discern archaeologically, time period by time period. Use of multiple archaeological datasets – data on households, mobility, subsistence, demography, exchange -- provides several distinct points of comparison between both the “macro” and “micro” aspects of model social systems and archaeological data. Archaeological data are the direct evidence of what we’re trying to understand: in order for an explanation to be convincing, it needs to be concordant with that evidence.

A Grand Challenge

In a recent paper in PNAS, Keith Kintigh and fourteen other authors discussed the “grand challenges” of archaeology. Understanding how social inequalities emerge was right there at number two. In my opinion, the emergence of social complexity is the premier issue that we can attempt to address using the Paleoindian, Archaic, and Woodland records in eastern North America. If this was an easy thing to do, however, we probably would have done it already. But that doesn't mean it can't be done. We could go a couple of different ways. We could simply point the finger at environmental change, or “population pressure,” or a combination of those, and declare the problem solved. There is precedent for that approach. Or we could take the challenge seriously and attempt to address it as a question of emergence, harnessing the potential of combining the vast archaeological information that we have access to in this part of the world with a new approach that gives us a chance to really understand what happened, how it happened, and why it happened. I know where I stand on this choice: I think we can and should try to understand the narrative as something other than a "just so" story. The story matters, and we have the tools to get it right.

In a recent paper in PNAS, Keith Kintigh and fourteen other authors discussed the “grand challenges” of archaeology. Understanding how social inequalities emerge was right there at number two. In my opinion, the emergence of social complexity is the premier issue that we can attempt to address using the Paleoindian, Archaic, and Woodland records in eastern North America. If this was an easy thing to do, however, we probably would have done it already. But that doesn't mean it can't be done. We could go a couple of different ways. We could simply point the finger at environmental change, or “population pressure,” or a combination of those, and declare the problem solved. There is precedent for that approach. Or we could take the challenge seriously and attempt to address it as a question of emergence, harnessing the potential of combining the vast archaeological information that we have access to in this part of the world with a new approach that gives us a chance to really understand what happened, how it happened, and why it happened. I know where I stand on this choice: I think we can and should try to understand the narrative as something other than a "just so" story. The story matters, and we have the tools to get it right.