Subsistence Economics, Family Size, and the Emergence of Social Complexity in Hunter–Gatherer Systems in Eastern North America (2013, Journal of Anthropological Archaeology 32(1):122-163)

|

This is a complicated paper with a simple goal: to try to understand how changes in family-level economics related to subsistence might have articulated with the long-term transformation between "simple" and "complex" hunter-gatherer societies in eastern North America. The emergence of social complexity is a fundamental issue of anthropological and archaeological inquiry, and is, in my opinion, one of the dominant archaeological problems to address in eastern North America. The transition takes thousands of years to unfold. It is one of our "bread and butter" issues, which is why, when I give talks on it, I show a slide of bread and butter:

I define a "complex" social system as one that is composed of unequal parts. This is in contrast to a "simple" social system that is composed of parts that are equal. There are, of course, inequalities of status among persons and families in all human social systems at any given time. The existence of those kinds of inequalities, however, does not necessarily make a social system is complex. A society is "complex" when inequalities among the parts of the system become permanent. In other words, the emergence of social complexity is tied to the emergence of ascribed (i.e., hereditary) status. I argue that, among hunter-gatherers, it is likely families/households

that become unequal. Where do those inequalities come from? What

happens to break the symmetry of "simple" societies?

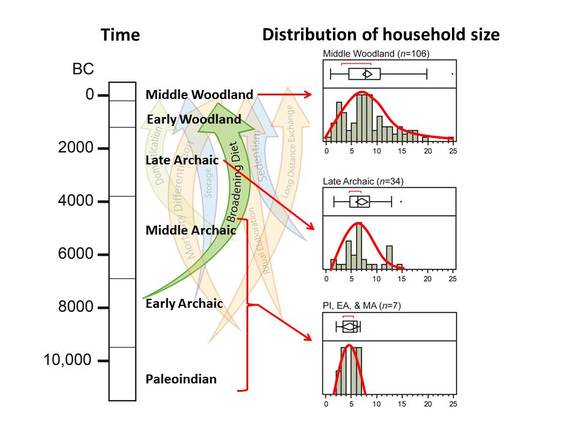

There are many threads in the transformation from "simple" to "complex" societies in eastern North America. In this paper, I focused on the role that subsistence intensification may have played in changing the economic calculus of individual families. I used a model to show that positive feedbacks between the productive and reproductive potentials of larger families produce right-tailed distributions of family size and ‘‘wealth’’ when the productive age of children is low and polygyny is incentivized. Under these conditions, social systems emerge which are composed of many smaller households and a few larger, wealthier households.

The main body of archaeological data I used for the analysis in the paper was the sizes of prehistoric residential structures. I collected data on over 800 Paleoindian through Middle Woodland structures in eastern North America and used those data to estimate the number of occupants in each structure. As shown in the illustration above, ongoing subsistence intensification during the Late Archaic and Woodland periods appears to be associated with distributions of family/household size with increasingly pronounced right tails. This is consistent with the idea that the distributions of family/household size changed during those periods in a fashion consistent with the results from the model.

This was a broad brush analysis. Although this paper (available here) was long and complicated, it really only takes a first swipe at the problem. More detailed modeling work will be required, as will more and different kinds of archaeological data. I used the dataset of residential structures that I assembled for this paper as the seed for the Eastern Woodlands Household Archaeology Data Project, an initiative to compile and make available data on prehistoric residential structures in eastern North America. A future consideration of a large scale dataset will be coupled with more detailed analyses focused on understanding changes in within- and between-household social relations during the Archaic and Woodland periods. |