A Developmental Perspective on Technological Change (2008, World Archaeology 40(4):597-608)

|

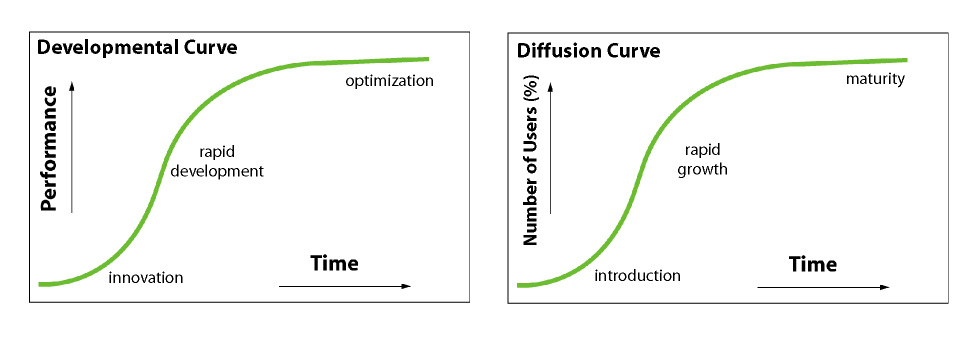

This was my first publication that combined computational modeling and archaeological data. The main argument of the paper is that processes of technological change are understandable and generalizable to prehistory. First, I used a really simple agent-based model to demonstrate how a basic trial-and-error "search" process produces an S-shaped curve of performance increase through time. These kinds of curves are well-studied phenomena. In cases of technological development, a period of rapid performance increase is often followed by a period of more gradual improvement as a technology is optimized.

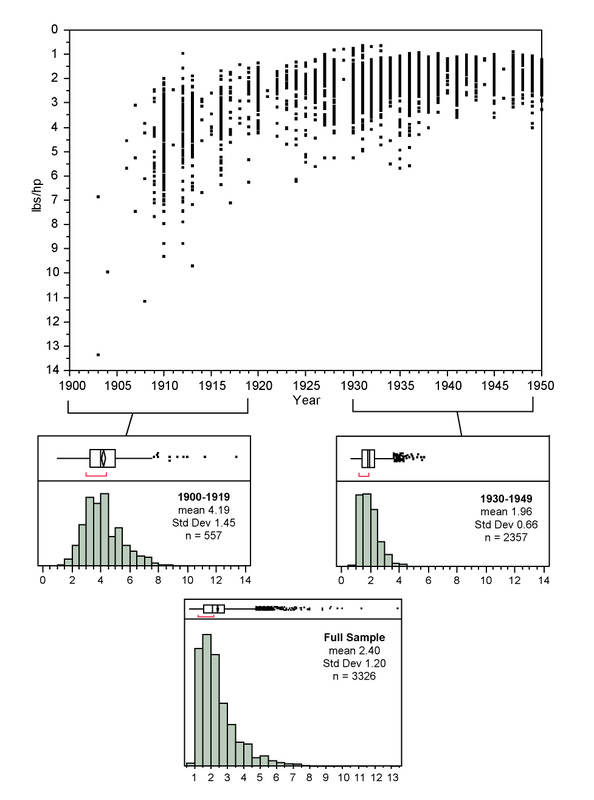

Model results showed that as development progresses through these rapid and more gradual portions of the S-curve, the amount of variability in examples of the technology per unit of time decreased. Examples of the technology are more variable per unit of time during the period of rapid development because development is proceeding so rapidly. This suggests that assemblages of "early" artifacts should be more variable than assemblages of "late" artifacts if three things are true: (1) a trial-and-error process of technological development is operating; (2) "early" and "late" assemblages of artifacts are drawn from periods of time that are comparable in length; and (3) an appropriate performance-related metric can be identified.

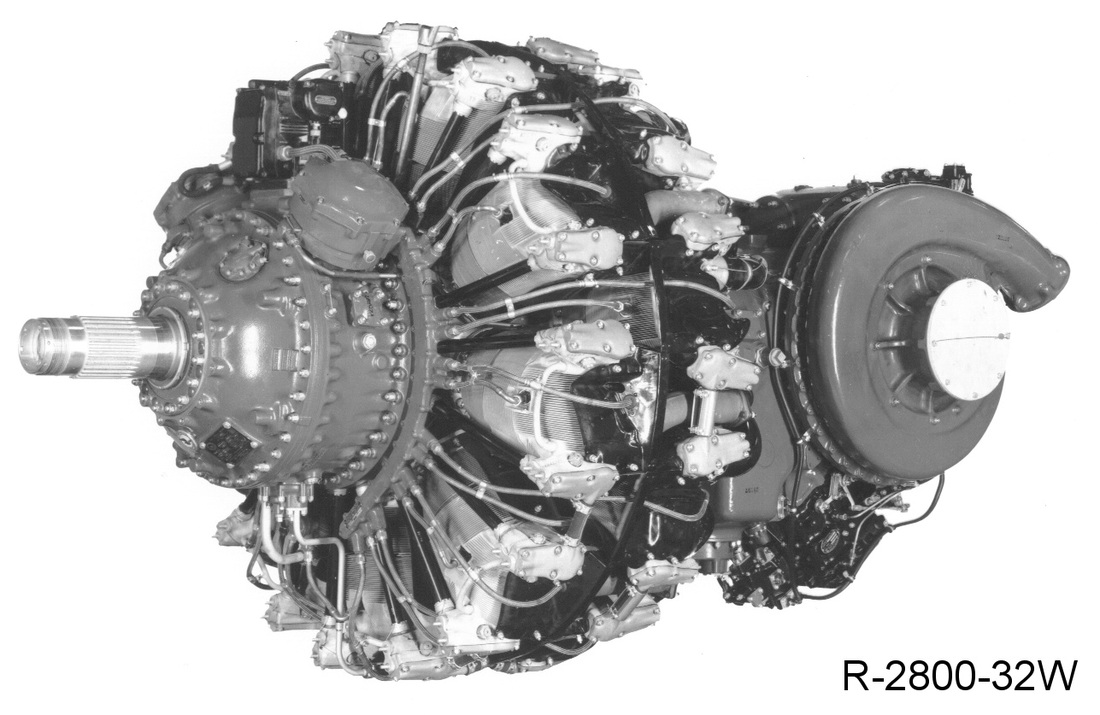

I then compared these results to an example of technological change where year-by-year data on performance were available: aircraft piston engines. The path of performance increase in this technology (as measured by the ratio of weight to power) is clearly non-linear, with a period of rapid development followed by a period of more gradual optimization. The statistical properties of "early" and "late" assemblages of engines are also as expected, with much greater variability in the early stage of development. This example also highlights the relatively scarcity of early examples of a technology: this is result of the combination of S-shaped curves of both development and diffusion (see figure above). Early in adoption, technologies may change rapidly and be used by relatively few. There was only one original Wright Brothers engine ever made, while there were thousands of Pratt & Whitney Double Wasp engines produced. Which would be more likely to show up in an archaeological assemblage?

I then briefly discussed an archaeological example (fluted point technologies) in light of some generalized expectations for non-linear paths of technological change. I didn't have the archaeological dataset I needed at the time, or the space in the paper, to do a full analysis of fluted point development. I am much closer now to having suitable data: I compiled a much larger dataset for my dissertation, and have made a start of partitioning aspects of functional and stylistic variability in Paleoindian and Early Archaic points. I've also been assembling a massive dataset on change in various historically-documented technologies. Maybe I will revisit the ideas in this paper soon.

I first presented the ideas in this paper at an invited workshop on Paleoindian archaeology. The reaction to the presentation I gave was mixed. Some people saw the value in what I was trying to do, and others clearly did not. I perceived a lot of head scratching and received a lot of feedback. Some of the feedback was constructive, but much of it was fairly negative. I was even told at one point, point blank, that what I was doing had no value. "More culture-history, less modeling" . . . that was the way forward. In retrospect, I shouldn't have been surprised. But it was an eye opener at the time. I don't think we should assume that, for some reason, technologies that we can observe archaeologically follow fundamentally different rules of change than those we can observe in the present. I think, rather, that we should make an attempt to understand the mechanisms underlying change and try to develop expectations that will help us identify those mechanisms in archaeological assemblages. This may go a long way toward understanding why rates of change in material culture seem to be so variable across time and space. Of course there are many challenges to applying these kinds of ideas to archaeological assemblages, but it is our job as archaeologists to figure out how to do that. That requires modelling and theory-building. You're going to spend a long time sitting in a quiet lab if you decide to "just let the data speak for itself." Anyway, it was apparent that my paper did not fit with what most of the others at the workshop were doing. I decided that I would submit a different paper (Paleoindians in northern Indiana) for the edited volume that would be produced from the workshop. As I was working on that, Mike Shott contacted me about doing a short paper on the work I had presented for a "Debates" volume of World Archaeology he was editing. I happily agreed, and that became this paper. Some time later, well after I had finished a draft of my paper on northern Indiana Paleoindian paper, the proposed edited volume that was supposed to come from the workshop was cancelled. All that northern Indiana data, with all the requisite source-to-discard diagrams, etc., was incorporated into my dissertation (and subsequently, papers in North American Archaeologist and Archaeology of Eastern North America) in a way that, I hope, will ultimately be more useful than yet another paper stating that Paleoindians moved tools long distances across the landscape. |