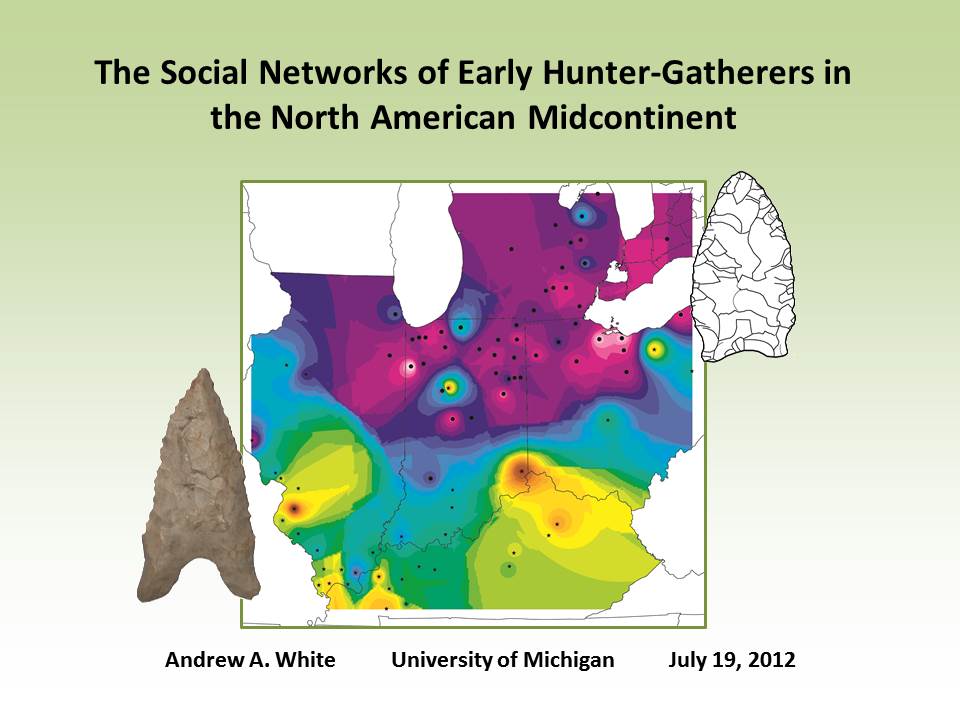

The Social Networks of Early Hunter-Gatherers in Midcontinental North America

My dissertation was complicated. Several of the main subjects of my doctoral work (hunter-gatherers, complex systems theory and generative social science, Eastern Woodlands prehistory, and social networks) are discussed in other parts of this website. This section provides a short summary of my approach to the problem, some discussion of the modeling and data collection work, and a brief description of my conclusions. If you want the nitty gritty details of what's in the dissertation, your best bet is to read the actual document. If you want to see photographs of a V-1 rocket, rainbows, and a two-headed calf, you're in the right place.

|

What I Did and Why I Did It

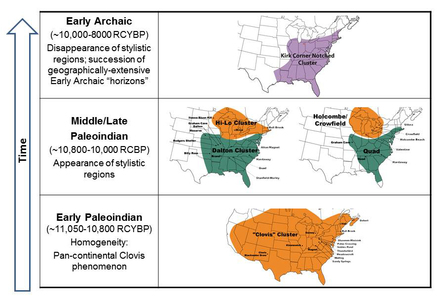

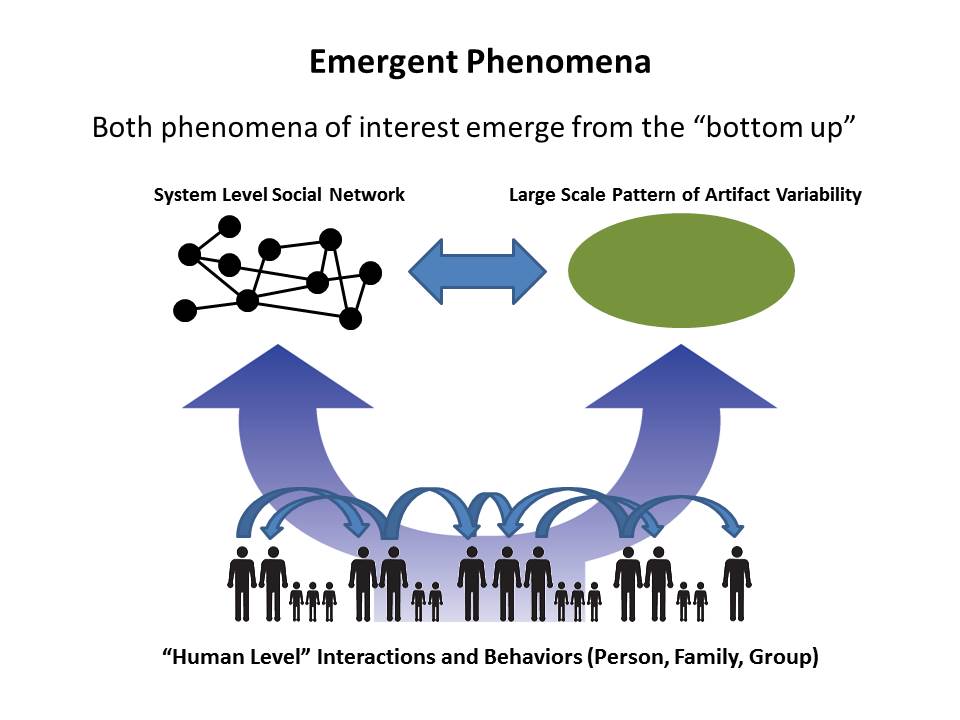

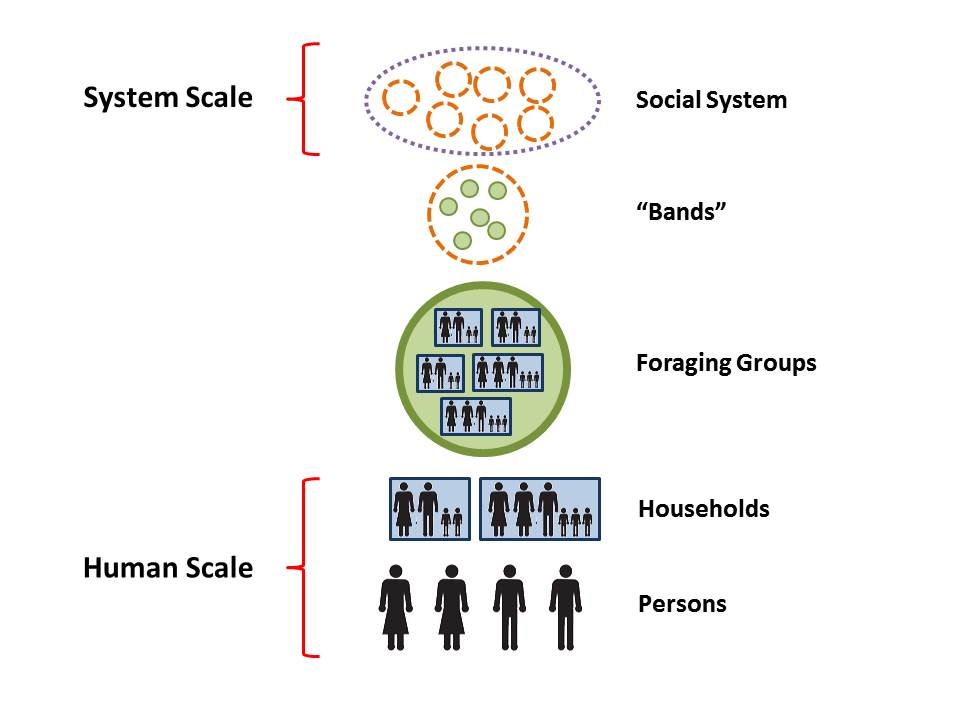

I used a combination of agent-based modeling and archaeological data to try to do two main things: (1) build theory about the characteristics and properties of hunter-gatherer social networks; and (2) explore how the characteristics of social networks are related to patterns of variability in material culture whose production is mediated through those networks. My goal was to build a basis for evaluating alternative network-based scenarios explaining some interesting aspects of the Paleoindian and Early Archaic records in Midcontinental North America. In this area, as across the Eastern Woodlands, stylistic regions appear during the Middle/Late Paleoindian period (ca. 10,800-10,000 RCYBP) then disappear during the subsequent Early Archaic period (ca. 10,000-8,000 RCYBP). Why? What do changes in social networks have to do with this phenomenon? What were the social networks of these early hunter-gatherer systems like? What mechanisms were involved in their formation and maintenance? How did they transfer information? What effects did changes in the organization of hunter-gatherer systems during the Pleistocene/Holocene transition have on these networks? Good questions! And important ones, too. Not only are these questions relevant to understanding Paleoindian and Early Archaic societies, but they are relevant to understanding the narrative arc of the remainder of prehistory in eastern North America. Processes of change act on initial conditions, and those initial conditions matter to the outcome. If a process is a recipe, the initial conditions are the ingredients. Boiling eggs for 15 minutes will produce a different outcome than boiling sap: same process, different inputs and different outputs. In my opinion, we must understand the social fabric of the earliest cultural systems in the Eastern Woodlands to understand everything that comes later. The people, groups, structure, and organization of those societies are ingredients for the processes of change that unfold over the next ten thousand years. We must understand how these earliest societies in eastern North America were wired together in order to understand how and why they changed. The archaeological literature contains many statements about the social networks of Paleoindian and Early Archaic peoples. Almost all of them, in my opinion, are rather simplistic interpretations that were based on some pretty informal inductive reasoning. Many of them are contradictory. How can we give ourselves a chance to determine which, if any, of these explanations make sense? Another good question. I used complex systems theory, a large archaeological dataset, and the principles of generative social science to try to build some basis for doing that. I designed and developed a model hunter-gatherer system (called ForagerNet2) that I could use as tool for building theory and evaluating archaeological explanations. By making individual persons the fundamental units in the model, I could represent human-level behaviors, mechanisms, and constraints (such as marriage, reproduction, mortality, mobility, and social learning) at the levels in a social system where they actually occur. I could alter the value of a parameter that affects the formation and maintenance of personal social networks, such as the frequency with which persons moved between groups, and analyze how that change affected the characteristics and properties of system-level social networks. This was a way to build anthropological theory. Because I configured the model to produce outcomes in terms of material culture, I could also use it as a tool for building archaeological theory. The model system is a "known" that can be used, through comparison of empirical outputs, to understand the conditions and processes that could have produced the patterns associated with an archaeological case. Model-based analysis of this kind - incorporating both inductive and deductive approaches - is what Robert Axelrod terms a "third way" of doing science. This is a powerful way to help archaeology push past some of the equifinality problems that currently hamper our ability to make confident interpretations of the past. It is also a lot of work. |

|

Modeling

Agent-based modeling was an integral component of my research strategy. In generic terms, a model is simply a description of how variables are related to one another. An agent-based model (ABM) is a specific kind of model that is useful for understanding how the higher-level behaviors in a complex system emerge from the interactions of numerous individual "agents." ABMs are great tools for understanding hunter-gather social systems because they allow one to represent important behaviors -- such as marriage, reproduction, mortality, kinship, mobility, and social learning -- at the "human level" where they actually occur. I would guess that the modeling component of my dissertation accounted for the majority of effort I put into my doctoral work. That goes for just about any metric you choose to characterize "effort": time, energy, frustration, anxiety, withered social connections, lost sleep, etc. I couldn't even guess how many hours I put into learning Java and Repast, writing code, debugging, running experiments, re-running experiments, etc. Over the course of several years I went from knowing nothing about computer programming to producing a fairly sophisticated, flexible model of hunter-gatherer social systems that I could use to address a variety of questions. During this time I didn't pay a whole lot of attention to the modeling activities of other people who were interested in hunter-gatherers. This was a conscious decision. I wanted to work within the constraints of time and energy that I had, produce a model that I thought put the appropriate emphasis in the appropriate places, and go through the process of solving problems (with representations, coding, operation, etc.) on my own as much as possible. I went through several generations of simpler models along the way to producing the ABM (ForagerNet2) that I would use for my dissertation. I used one of these for the analysis in this paper in the Journal of Artificial Societies and Social Simulation (code and description are available here). I used the FamilyNet model, which was essentially a non-spatial version of the ForagerNet2 model, for the JAA paper. While I used other models to produce data for various presentations, etc., they were mainly developmental "test beds" that served as platforms for working out the various problems associated with the main model I was trying to build. I think it would be wise to go back a few steps and use some of those simpler models (or improved versions of them) as tools to look at some basic theoretical issues. That would be much easier to do that now that the dissertation work is completed. I'm not sure when I discovered that putting a song on a loop and listening to it over and over again helped me with the computer work. I did it a lot: Depeche Mode's Question of Time, Metallica's Whiskey in the Jar, Silver Threads and Golden Needles and Carmelita by Linda Ronstadt, and Judas Priest's Heading out to the Highway. Yes, the drummer in Judas Priest is wearing a skinny tie. You're welcome. |

|

Archaeological Data Collection

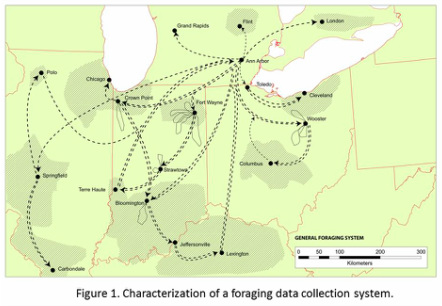

The primary archaeological data for my dissertation consisted mainly of morphometric and raw material information from Paleoindian and Early Archaic projectile points. I needed points from across a large area (Illinois, Indiana, Kentucky, Michigan, Ohio, southern Ontario), so I spent most of my data-gathering effort driving around the Midwest visiting collections in various places: the Field Museum, Ohio Historical Society, Dickson Mounds Museum, Ball State University, Cleveland Museum of Natural History, Webb Museum, Glenn Black Lab, Grand Valley State University, Southern Illinois University, Indiana State University, the University of Western Ontario, Illinois State Museum, and IPFW. I also looked at collections in county historical societies and private hands when I could make it happen. Based on my camera's smile detector, many of the points were very happy to see the light of day after decades (or longer) in boxes and bags. Crisscrossing this research area by car a few times really helps you appreciate its size. Most archaeologists (at least in this part of the world) do not work at such a large spatial scale, but I think you have to in order to attempt to address a question like the one I chose. How can you hope to say anything meaningful about the social networks of these spatially-extensive early hunter-gatherer systems without having archaeological data that matches or exceeds the scale of at least some portions of those systems? That's like trying to figure out the picture on a jigsaw puzzle while only bothering to look at pieces from one corner. There are more than enough dissertations written these days that claim to address a very large question (e.g., the origins of warfare, the spread of an empire) with very small, focused datasets (materials excavated from a small area at a single site). I wanted to avoid that kind of gross mismatch in scale and collect a dataset that would give me a chance to actually address the issue. The best way to do that in this case was by harnessing the potential of existing collections from across a large area, not by digging a 2x2 somewhere. This was very inexpensive work as far as archaeology goes: gas, hotel, and food on the road for one person. I ended up paying for some of it myself.* I applied for an NSF Dissertation Improvement Grant to cover the travel costs, but I didn't get it. The two reviewers who understood what I was trying to do thought the proposal was solid and recommended that it be funded. One of the other two said that he/she didn't believe that modeling ever produces results (so . . . that's a "no"?). The other one said that what I should really be testing was Caldwell's 1958 model of Primary Forest Efficiency. It would have been nice to have the NSF "feather," but I did the work I wanted to do without help from the Federal Government. A five dollar bill for every time I heard Taylor Swift's You Belong With Me on the radio would have funded a significant of this portion of my collections work. Anyway, I'm all done and eagerly awaiting the results of someone's federally-funded research determining whether or not the 1958 model of Primary Forest Efficiency is "true." The critical aspect of the research design, of course, will be the placement of the 2x2. The best thing about traveling alone by car was that I could take whatever route I wanted to, stop when and where I wanted to, and listen to whatever music I wanted to. I visited some old friends and made a few new ones. I slept on couches, in guest bedrooms, in farm-themed rooms, and in a lot of Motel 6s. I put some pretty hard miles on my car, drove through blistering heat and one of the worst ice storms I have ever seen. I caught up on paperwork in laundromats, saw a lot of good weather, bad weather, and bizarre weather, and ate a lot of peanut butter and jelly sandwiches. During my downtime I stopped at antique malls, airfields, car and tractor shows, a motorcycle museum in a church, and a place that sold what appeared to be satanic concrete statuary. I spent summer evenings walking in downtown Chicago, betting on horses in Lexington, and trying to find something to do in Havana, IL, besides drink beer and watch Cass County Idol on the television. I would love to someday write an archaeology/anthropology of the "unmapped" Midwest. It all feels like home to me. There are interesting things everywhere: some are obvious and some are not. It is really interesting to me how your brain (and by "your brain" I mean "my brain" - maybe not everyone does this in the same way) turns these peculiarities into landmarks in the process of creating a mental map. I have no idea how many small towns in eastern Illinois I have driven through, but I remember Milford because I happened upon a V-1 rocket in a park by the gas station while I was passing through one evening. Much of the remainder of my mental map of eastern Illinois, however, is occupied solely by sea monsters. Maybe this is a project I'll work on if this whole "academic archaeology" thing doesn't pan out. |

|

Analysis and Conclusions

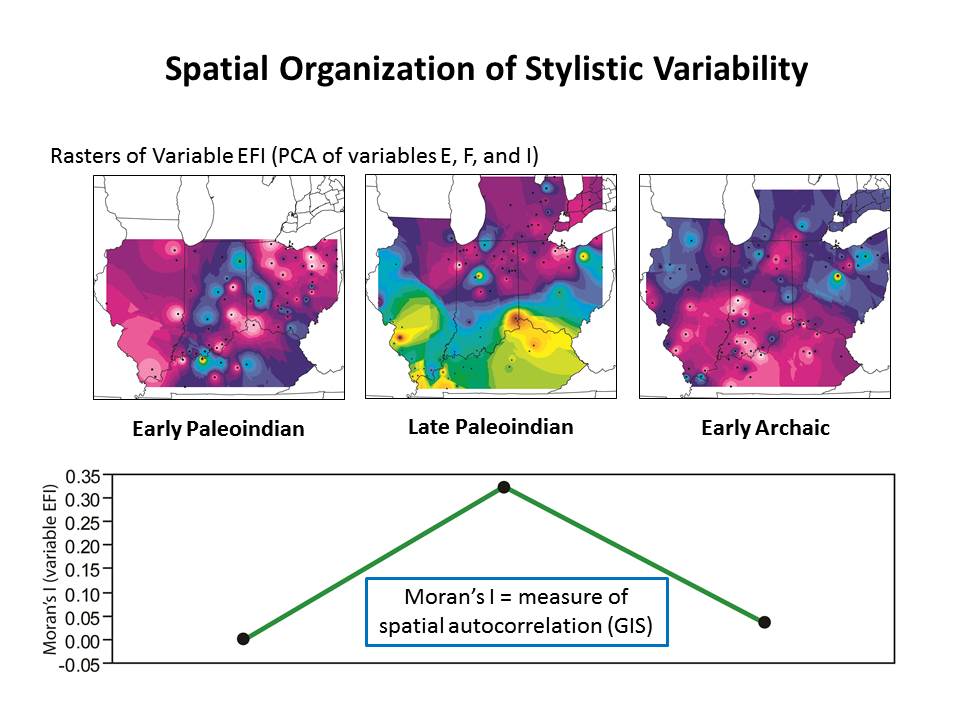

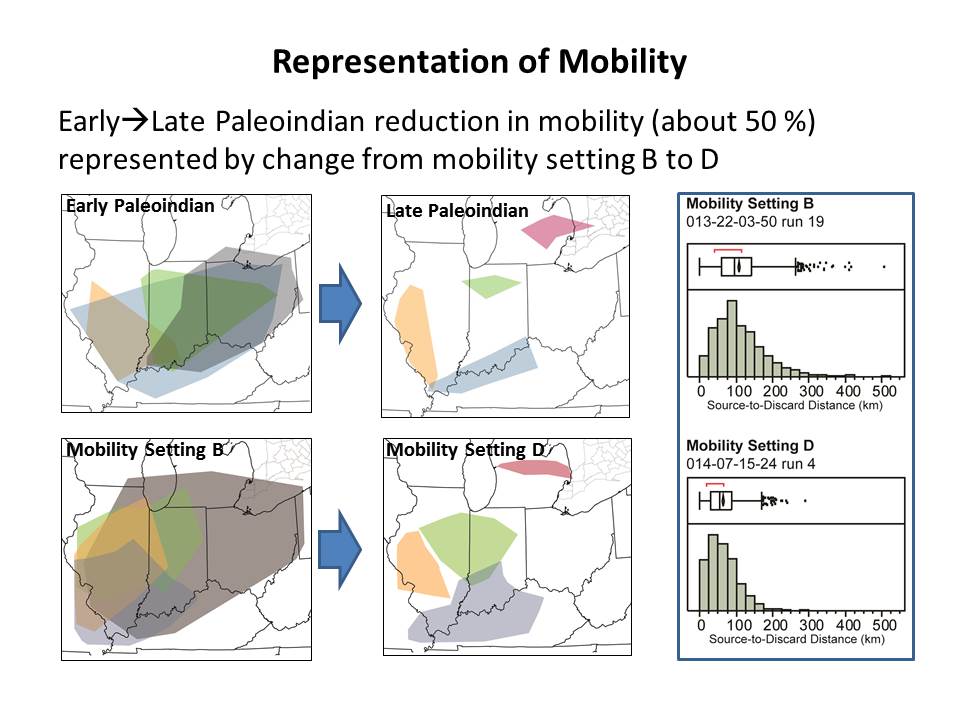

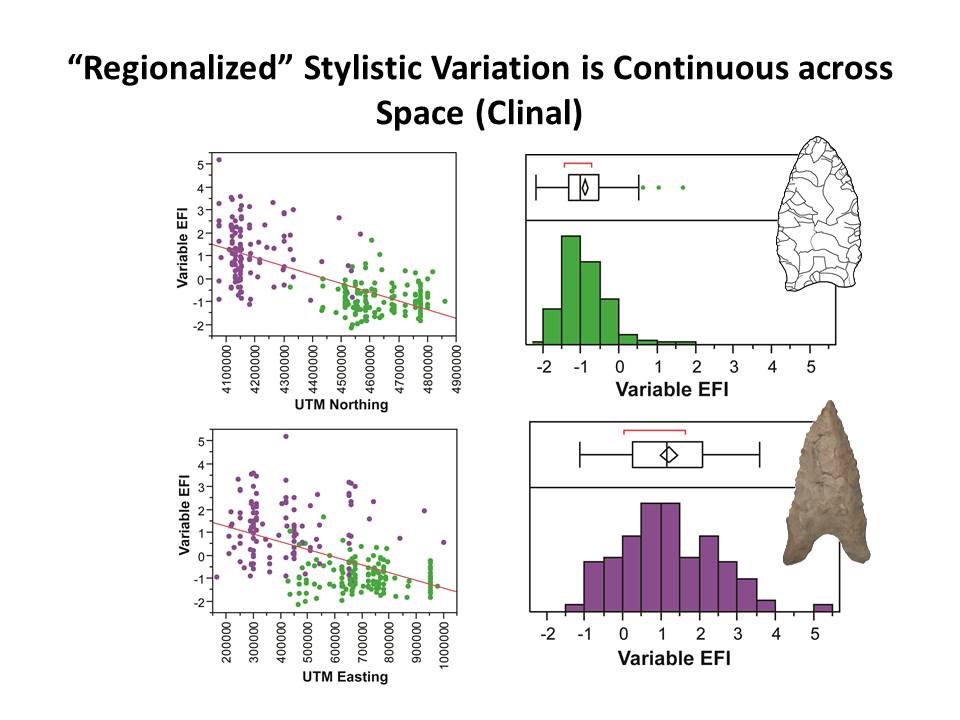

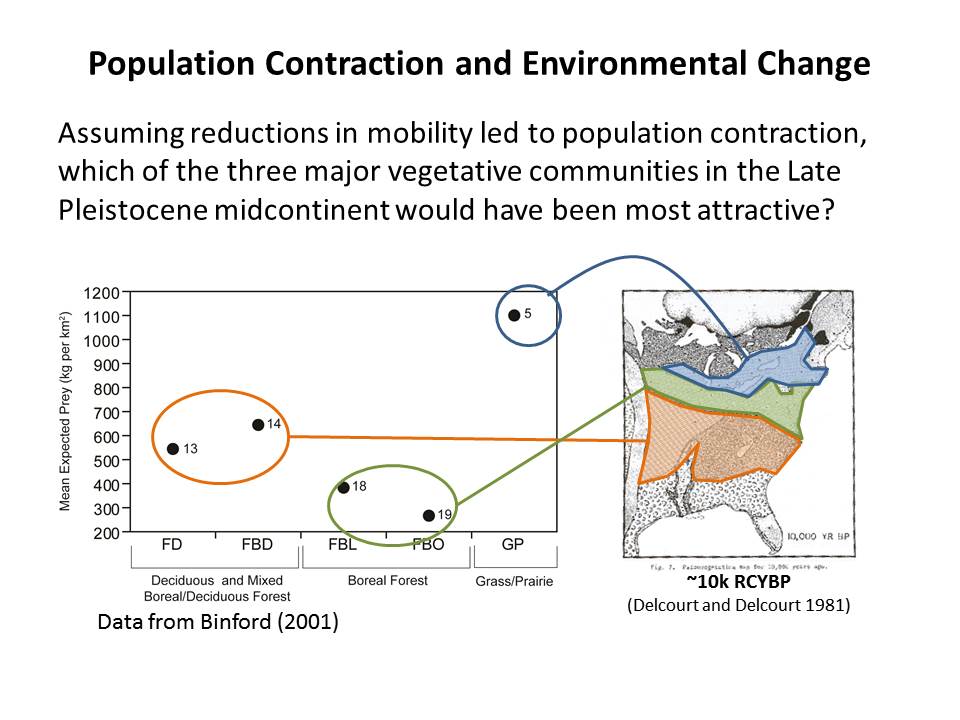

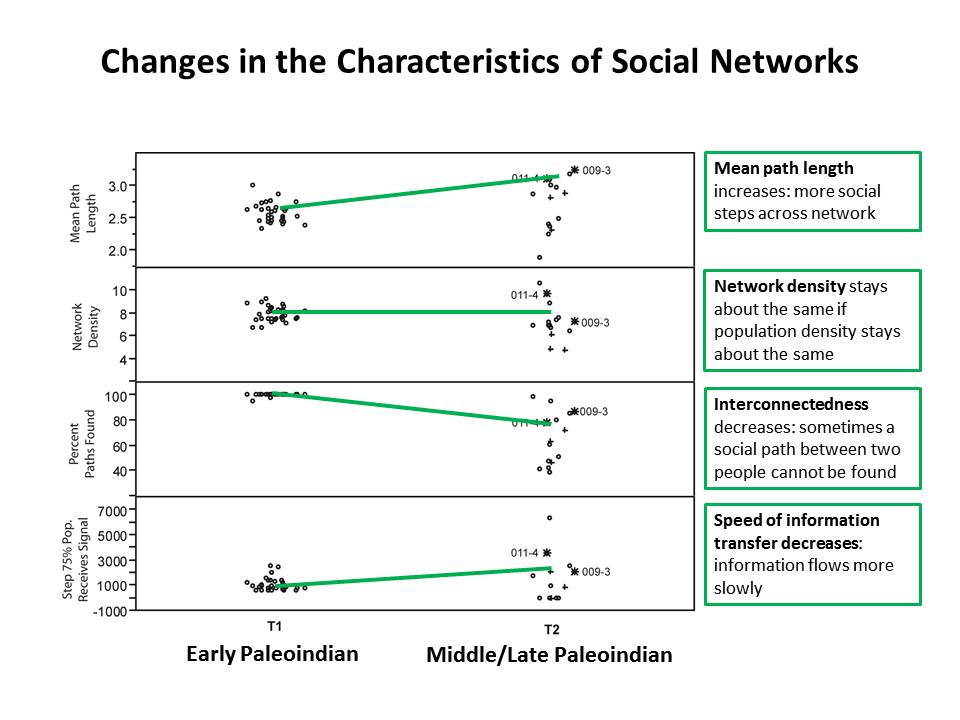

When I started my dissertation, I had hoped to be able to address the entire sequence of homogenous-regionalized-homogenous that characterizes the Paleoindian and Early Archaic periods. When it came down to it, however, I simply ran out of time. Individual model runs simulating the entire Paleoindian-Early Archaic time sequence were just taking too long to get enough of them completed in time to be analyzed and included. Being able to systematically vary the values of parameters and do a large number of experiments in order to understand how outcomes are distributed (i.e., what is the range of possible outcomes? which outcomes are common and which are rare?) is one of the real strengths of this kind of model-based analysis. When it came down to the wire, however, I just didn't have the combination of time and computer resources I needed to do everything I had hoped to be able to do. I had to focus on trying to understanding the role of changes in social networks in the first historical event in the sequence: stylistic regionalization. My analysis of the morphometric data that I collected from projectile points was geared toward quantifying the changes associated with stylistic regionalization in terms that I could compare to outputs from the model. An important aspect of this analysis was to make a determination about which aspects of variability in these tools could be considered "stylistic." My approach to that question is discussed in a recent paper in North American Archaeologist that is drawn from my dissertation work. I "calibrated" changes in parameters of group mobility in the model social systems to match those suggested by changes in raw material transport distances in the projectile point sample. An upcoming paper (hopefully available during the Summer of 2014 in Archaeology of Eastern North America) discusses the raw material data (though not the comparison to model data). The regionalization of style associated with the Late Paleoindian period is clearly visible when stylistic variability is plotted across space (see top figure in this section). While we knew that Hi-Lo and Dalton were similar but different, my work produced a description of how stylistic variability between these two technologies is distributed across space. It appears to be clinal: it varies continuously with space rather than plotting as two distinct groups. The appearance of this clinal pattern of variability, absent among the preceding Early Paleoindian technologies, was an important clue. What changes to social interaction would have to be imposed on our model Early Paleoindian societies to produce this sort of clinal variability? Could we trigger, from a homogenous initial condition, the appearance of clinal variability by imposing an "active" social boundary between regions? What if we imposed a "passive" barrier that reduced interaction? How strong would such a barrier have to be in order to allow stylistic divergence to take place? These are modeling questions. Spoiler alert: Based on my analysis, I concluded that the appearance of stylistic regions during the Middle and Late Paleoindian periods was most likely the result of processes of stylistic drift operating across social networks that were less inter-connected than those of the Early Paleoindian period. Decreasing social connectivity was probably related to an uneven distribution of population as hunter-gatherer individuals, groups, and systems responded to environmental change at the end of the Pleistocene. In essence, I think that changing environments at the Pleistocene/Holocene interface led to a significant decrease in the scales of mobility of these earlier foraging groups. If the scale of group mobility decreases by half but everything else stays the same, the population would have to quadruple in order to maintain the same density of persons across the entire landscape. While populations were probably growing at the end of Pleistocene, I doubt they were growing that fast. In order to maintain systems with a viable fabric of social interconnectedness, populations would have had to contract. The boreal forest areas of the Midcontinent would likely have been the least attractive areas, leading to contractions into the Great Lakes and the Southeast. This would have left portions of the Midcontinent largely empty and making it difficult to maintain a continuous social fabric across the Eastern Woodlands. Decreased social connectivity would have slowed the transfer of information and allowed drift processes to produce stylistically differentiated regions. While decreased social connectivity at the system level may have allowed stylistic differentiation of material culture to occur, I doubt most of the changes in social networks would have been perceptible at the level of day-to-day human experience. Individual persons would have had personal networks of about the same size and composition, produced and maintained through many of the same mechanisms. A desire to maintain social connectedness with individuals in more distant populations may have encouraged the elaboration of formalized mechanisms for doing so (e.g., exchange). Population growth and the emergence of relatively homogenous environments at the beginning of the Holocene (ca. 10,000 RCYBP) would have increased social connectivity as the landscape was "filled in" during the Early Archaic period. |

|

Done and Done

I defended my dissertation in July of 2012. My committee was composed of Robert Whallon (chair), John Speth, Henry Wright, and Rick Riolo. John O'Shea participated in my defense as a replacement for Henry, who was unavailable overseas at the time. *Some of the archaeological data in my dissertation were collected prior to my doctoral work. The State of Indiana funded three seasons of what I called the Northern Indiana Paleoindian Project, which was a data collection, survey, and public education effort focused in northern Indiana (technical reports available on my Academia.edu page). I was supported during my doctoral work by funds from the James B. Griffin Endowment Fellowship (University of Michigan Museum of Anthropology) and a Rackham Predoctoral Fellowship (Rackham Graduate School, University of Michigan). Funds were also provided by the University of Michigan Department of Anthropology and by John Speth through his Arthur F. Thurnau Professorship. |