"The fact that everyone has a platform, right this minute, means that the only reason you're not using it is because you don't want to, not because you're not allowed to."

I think he's right about that (and a lot of other things, also -- you should listen to the interview).

I've been developing my online presence since the Spring of 2014. There were a number of reasons why I committed to doing it. At the top of the list is that I thought it would help me on the job market. My career path has been somewhat non-traditional, with a long period of time between getting my Master's degree and going back to school for my Ph.D. While that "gap" was filled with archaeology (and starting a family), it put me into Michigan's doctoral program at a different point in my life than most of the other students. I had an incentive to finish quickly, so I designed my dissertation work around data from existing collections and computer modeling rather than as a more traditional, site-based project (that wouldn't have answered any questions I was really interested in and wouldn't have given me any excavation skills I didn't already have).

Anyway, I felt that the professional path I had chosen was putting me at a disadvantage. I was having success getting short list interviews, but the easy choice for many departments seemed to be a person who had a narrowly focused research agenda that involved continuing work at a single site. That's not me. I thought building a website would help even the playing field a little, allowing me to present my ideas in a way that would help people (especially people on search committee) understand them and see how the various components of my research agenda fit together. I've always tried to be who am, and I thought I would be better off working to present a more accurate picture of myself rather than trying to pretend I was someone else.

In reality, I don't think that my online activities actually helped me get a job in a direct way. I don't know that they played any role landing my Visiting Professor position at Grand Valley State, and I doubt they had much to do with getting my current position at South Carolina.

But that doesn't mean they weren't worthwhile. I think putting my website together and writing a blog, probably did help me in a number of indirect ways. Writing content for my various "Research Interest" sections was a good exercise in boiling down and making connections between the various things I'm interested in (my work is complicated and difficult to explain in the kinds of simple sound bytes you need to sell yourself during an interview). So that was good. I put less effort into that part of my website (much of it remains "under construction to this day) as I discovered that I like blogging. That's where the real fun has been for me.

I think blogging has been beneficial in several ways: (1) it has helped me become a better writer (and a better communicator overall); (2) it has forced me to learn to think carefully about what I'm going to say before I say it, knowing that it can be read by anyone (including the people whose work I'm discussing); (3) it has let me make connections (both positive and negative ones) with a variety of people whose interests overlap with mine; and (4) it has given me an outlet to share my ideas about whatever I find interesting, whether related to archaeology or not (I've written about dragonflies, aircraft, and one of my large metal dinosaur sculptures, among other things).

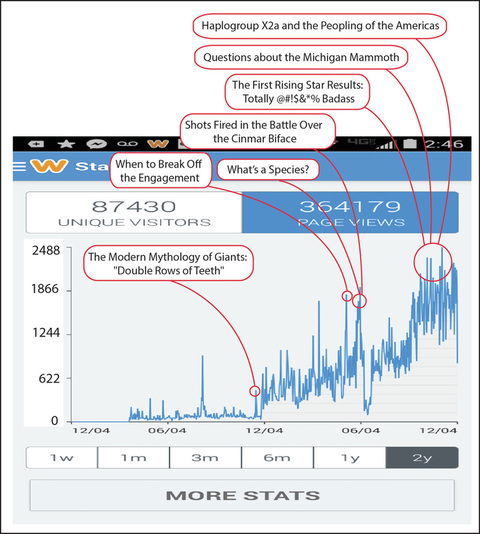

A screenshot of page views by day shows some pretty steady growth starting in December of 2014. The post that really started growing my readership was the first thing I wrote about "double rows of teeth" at the end of November 2014. I had been collecting data about accounts of giants for some time, and I thought I had the "double rows of teeth" mystery cracked. The ridiculousness of Search for the Lost Giants prompted me to use my blog (rather than an article) to try to communicate my results. That was a good move: I got a lot more positive feedback (a lot more quickly) than I ever would have using traditional print media.

Believe it or not, I was initially somewhat timid about naming names and directly engaging online with ideas and people. As I wrote more about giants and saw the results, however, I realized that I had something worthwhile to contribute and that I could not only participate in a conversation but affect it. I've written a lot about giants over the last year, and I've been surprised by how few "giantologists" have been willing to engage with me. There are a few, to be sure, and I've enjoyed having conversations with them (even when we disagree). Some of the people whose work I've called out, however, have ignored everything I've written while continuing to claim that "mainstream academics" (like me, I suppose) are too scared to deal with the phenomena they do (see my recent review of the chapter on "double rows of teeth" in Jim Vieira's new book). That's baloney. I continue to think that engaging with the "fringe" is useful, and I'm going to keep on doing it here and in other arenas.

I realized after a few months of writing about giants (during whatever time I could find while in the trenches of teaching a 4/4) that I was probably putting together the pieces for a book. "Research via blogging" is kind of a nice way to go, because what you write at any given time can be long and involved or short and simple. It really is possible to use blog posts as building blocks which can be assembled later into something larger and more complex. I find it much easier to keep track of my thoughts when I can just refer back to a titled blog post through a link rather than search through some long Word file or try to find some note that I scrawled on a scrap of paper somewhere. So there will be a book on giants that emerges some day from all this. I don't know when or what format it will be in (online or traditional), but it's coming.

While writing about giants (which I find to be an intrinsically interesting topic for many reasons) has increased my readership, many of my more popular posts have been about other things. I can usually tell within a few minutes when I've written something that has legs, as I start getting rapid notifications from Facebook and Twitter. That happened with the first post I wrote about the Solutrean Hypothesis ("Shots Fired in the Battle Over the Cinmar Biface") and this post I wrote after the announcement of yet another new species of australopithecine ("What's a Species?). The species post was later quoted in an NPR science blog, which was cool. The post on the Solutrean Hypothesis (the first of several I have written) got a lot of positive reaction. It also got me some angry comments and emails from some archaeologists, including a researcher at the Smithsonian. I continue to think the Solutrean Hypothesis is interesting both because of the evidence that is used to support it and for several reasons that go beyond the archaeological data. I'll continue to write about it when I've got something to say.

During my first semester at South Carolina I've had less time to write than I would like, but I've still made an effort to feed the blog when I have the opportunity. Some of my most popular posts this fall include one that I wrote about the excavation of a mammoth in Michigan ("Questions About the Michigan Mammoth") and one about the announcement from the Rising Star Expedition ("The First Rising Star Results: Totally @#!$&*% Badass"). I've been wanting to write more about the fallout from Rising Star, but I haven't found the time. The battle over "was this good science" (see, for example, this article, this post by John Hawks, and this piece) has been fascinating to watch. I think it's an incredibly important, multi-faceted discussion and at some point I'll probably have something to add and will (for better or worse) chime in again.

It's interesting to me that there is not a strong correspondence between the effort I put into writing something and how popular it seems to be. I think other academics can relate to this, as it's definitely true in print media as well. When I decide to spend effort writing something, I don't tend to worry too much about how many people will read it. That's probably for the best, as it allows me to continue to write about whatever I want. I will admit that it's a bit of a bummer to feel like I've been ignored, though, when I think I've said something that should be broadly interesting. I wrote this post about Ben Carson's thoughts on evolution way before all the hubbub over his misinterpretation of the pyramids. In a fair world, it would have gone viral. But it didn't: the pyramid post did. Why it surprises anyone that a Young Earth Creationist would say something silly about the human past is beyond me . . . you're all late to the party!

I have written quite a bit about how religion articulates with various "fringe" ideas about the past. Directly challenging religious notions, like directly challenging individuals, was something I was originally hesitant to do. I'm not anti-religion. As I learned more about why people believe in giants, however, it became apparent to me that understanding the religious component was important. If it's important, you kind of have to talk about it. I decided that, for me, the rules of engagement are satisfied when religion makes a claim about the past that falls within the purview of archaeology and anthropology. So I've written a lot about creationism (and there's plenty more to come) and a little bit on the ideas and claims of Mormons regarding the prehistory of the New World. There's a bunch of really interesting stuff to be learned about how science has changed the world over the last few centuries and how religious traditions and ideas about the past are related to the place of "fringe" ideas in our world today. I'm not near as shy about discussing it as I used to be.

I recently launched The Argumentative Archaeologist, a separate site that organizes information about all kinds of "fringe" claims. The name came from J. Hutton Pulitzer, who apparently thinks that calling an archaeologist "argumentative" is a pretty good insult. It's not: it's a compliment. I hope to keep The Argumentative Archaeologist growing over the next year as I prepare for and teach a class on "Forbidden Archaeology."

As my readership has grown, I've gotten my share of both positive feedback and negative pushback. I have to admit that I like both (I've worked too hard on too many academic papers that have gotten too little reaction not to appreciate when people take the time to react to what I say). My wife can tell you about how my face lights up when I know that I'm about to strike a match. It's nice when people agree with you, but it's also pretty nice when they don't and you get to have a discussion about why.

In the NPR interview that I mentioned at the beginning of this post, Seth Godin notes that disruptive leadership can vary in its usefulness. The modern history of archaeology provides us with a great example of "useful" vs. "less useful" disruptive leadership in the Tale of Two Angry Archaeologists that is the lesson of Walter Taylor (1913-1997) and Lewis Binford (1931-2011). While each leveled a similar set of pointed (and valid) criticisms at the archaeological status quo, one (Binford) was much more effective at bringing about change. The difference (as I wrote in this essay) is that Binford's "disruptive leadership" provided a way forward while Taylor's critique was just a critique.

My online experience with the both professionals and the fringe has reinforced the Taylor-Binford lesson to me many times over: disruption and criticism are much more effective if you provide an alternative. If you say the answer is wrong, then what's a better answer and why is it better? Providing that alternative takes significantly more effort, of course, than simply launching a criticism. I don't always get it right (and sometimes, honestly, it is really hard to want to try). But I think that my willingness to try has contributed significantly to the growth of my audience.

If you're an anthropologist (or any kind of scientist, really) and you've been thinking about developing your own website and becoming an active public voice, I encourage you to do it. You should definitely do it. And you should listen to the interview with Godin: much of what he said resonated with my experience, and his analysis may help you decide to take the plunge. If you remain quiet, it's by your own choice and not by necessity.

For readers in search of further inspiration, I can only refer you to the song "The Hero" by Queen. Go!

RSS Feed

RSS Feed