What struck me about the reviews was not the rejection but the skepticism about the model-based analysis of archaeological data that I advocated. I wasn’t asking for money for that part of the work, so I didn’t spend much of the limited space I had to detail the approach I would take. But I did mention that I’d be using agent-based modeling as an analytical tool to try to connect patterns in household-level archaeological remains to the gendered activity patterns that might have been associated with those households. (To be clear: I’m under no illusions that this will be a simple thing to do, but it is something we’ve got to continue to wrestle with. We say over and over again how important the sexual division of labor is to hunter-gatherer families and societies, but we don’t really seem to be too worried about it in terms of its archaeology).

One reviewer wrote that I was arguing that I could simply “model my way out of the problem.” This is an interesting thing to say. First, I think it communicates a strange hostility/skepticism toward the particular kind of modeling that I do. Based on previous experience, I would guess that this kind of negative reaction to agent-based modeling is probably rooted in ignorance or misunderstanding about complex systems methods and theory. That’s fine – that’s part of the professional battlefield that I chose for myself. What bugs me more is that the statement seems to signal a fundamental misunderstanding about the existence and roles of models in archaeology in general.

A model is a representation of something, plain and simple. A model can specify how variables fit together, how one part of a system connects or affects another, what behaviors produce a certain kind of material signature, etc. It is an abstraction of reality that captures some aspect of reality. The distinction between an archaeologist who is “using models” and one who is not is a false one: all archaeologists use models. We use models to make the leap between the static remains we have in front of us and the human behaviors that produced those remains. We are all trying to “model our way out of the problem:” the problem is that we cannot directly observe the people, societies, dynamics, and behaviors we are trying to understand. That's archaeology.

The real distinction is not based on whether one uses models in archaeology, but rather what kind of models one chooses to use. Many of the models that archaeologists use are mental models that are based on logic or some intuitive understanding of how things “should” be related. Joshua Epstein (2008) makes a useful distinction between implicit models and explicit models:

“. . . an implicit model in which the assumptions are hidden, their internal consistency is untested, their logical consequences are unknown, and their relation to data is unknown. But, when you close your eyes and imagine an epidemic spreading, or any other social dynamic, you are running some model or other. It is just an implicit model that you haven't written down (see Epstein 2007).”

The paper from which that quote is taken is available from JASSS here. It is short and non-technical.

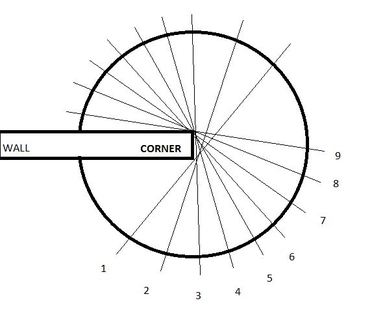

Humans (and other creatures) use implicit models constantly to navigate the world. When you look down the street and see a truck coming, you decide if you have time to safely cross the street before the truck gets there based on a model that lets you relate the key variables to one another (the truck’s distance, speed, acceleration, your speed, the width of the street, etc.). You can do all this without knowing the precise values for the variables or doing all the division and multiplication in your head: the model is a representation that gives you an estimate that is “good enough” (your life depends on it, after all). Similarly, a dog does not need to do the vector math in order to catch the Frisbee from the air: she uses a mental model to determine how/where to intercept the Frisbee.

Implicit models work great a lot of the time for doing archaeology. But they are not all we need. They can help us avoid getting hit by a truck, but are not so good for sending people to the Moon and back. Some problems require a different kind of modeling.

Archaeology is stuck in several spots. In many cases, we’re hampered by equifinality problems (multiple processes produce the same outcome). Maybe getting at gender in the archaeology of hunter-gatherers is one of those spots. How do we move forward? I suggest that abandoning models as altogether useless would be a much less effective strategy than adjusting the kind of model you’re using. How about trying something that fits the problem and gives you a chance to break the logjam? If you want to get a screw out of a piece of wood, try picking up a screwdriver rather than a hammer. I know it is a time-honored tradition to bang on the screw with a hammer and then give cautionary tale talks about how you shouldn't do that, but there may be room for another approach. Just a suggestion.

Yes, I’m going to try to “model my way out of the problem.”

RSS Feed

RSS Feed