You heard me: stone holes.

My last post on the subject asked why we should assume that hand-chiseled holes (which are irregular or triangular in shape rather than perfectly round) are medieval in age. There are several pieces of information (including experiments and first-hand accounts) that leave little doubt that the hand-chiseled holes being created in Minnesota in the 1800's and early 1900's would be difficult to distinguish from any holes left by a Norse expedition hundreds of years earlier. The discussion on that post didn't convince me that there's a good positive case to be made for the medieval origin for any of the stone holes: the work to develop and apply a reliable methodology for discriminating stone holes based on their intrinsic characteristics apparently hasn't been done yet.

I thought it might be fun to approach the problem from the other direction: let's develop a falsifiable hypothesis that all of the stone holes are of modern (i.e., post-Columbus) origin. I'll call it the "Boulder Field Quarry" hypothesis. I didn't invent this explanation, of course, but considering it as a formal hypothesis will be a useful way to demonstrate how you use an explanatory model (an explanation/description of how variables fit together) to derive falsifiable expectations that you can compare to empirical data. If it's possible to prove a hypothesis wrong but you can't do it after repeated attempts, you can start to have some confidence that you might be onto something. Here it goes.

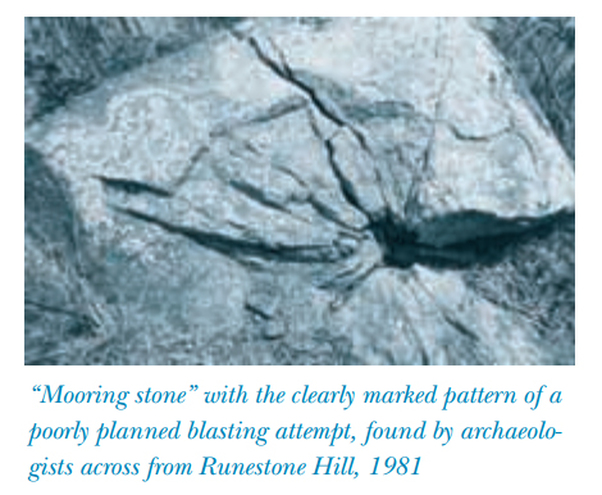

Glacial boulders in Minnesota were useful sources of stone for the Euro-American who populated the region in the 1800's. Holes chiseled or drilled into boulders were packed were filled with black power, gun powder, or dynamite. The explosives were ignited to break the boulders into smaller pieces which could be removed to clear fields and/or be used as building materials.

In The Art of Splitting Stone: Early Rock Quarrying Methods in Pre-Industrial New England 1630-1825 (2005), Mary Gage and James Gage discuss how this technique was used by German immigrants to New England in the late 1700's and early 1800's (pp. 24-25). Gage and Gage (pg. 25) describe round blasting holes with a diameter of about 1 3/16" (about 3 cm) and depths ranging from 4 to 20 inches (about 10-51 cm). New England blasting holes created after 1825 are slightly larger, ranging in size from 1.5-2 inches (3.8-5 cm) (pg. 25). Gage and Gage also note that "Generally, the hole was drilled into the top center of the boulder . . . Some surviving examples of blasted boulders have two or more blasting holes. The evidence indicates that an additional blast hole was drilled when the first blast was insufficient to break the whole boulder apart" (pg. 25).

- Boulders with one or more stone holes are too large to easily move in one piece or too large to use in the construction of building foundations;

- Stone holes are located on the top surfaces of boulders in locations suitable for blasting the entire boulder or removing significant pieces of the boulder;

- Stone holes are in the range of 3-5 cm in diameter;

- Stones holes are in the range of 10-60 cm in depth;

In the comments to the previous stone hole post, I mentioned repeatedly the need for a stone hole dataset that could be analyzed. This is why. The boulder field quarry model produces specific expectations for patterning in the placement, size, and depth of stone holes. In other words, it makes predictions which can potentially be shown to be false. Testing those predictions requires empirical data that can be used to quantify and characterize the stone holes. How wide are they? How deep are they? Where are they located on individual boulders? Are there any examples of small, intact boulders with stone holes?

Can the "medieval Norse origin" stone hole model produce a set of falsifiable predictions? I don't know. If so, I have yet to see those predictions clearly articulated.

That's one reason why the boulder field quarry hypothesis should be the null hypothesis. There are several others: it accords with multiple first-hand accounts, it's logical, and it fits with experimental, archaeological, and historical data from other areas. If you can prove that the stone holes weren't for blasting, I'm prepared to consider alternatives. But first you either have to show me why this explanation doesn't work (citing "because the Kensington Rune Stone" exists isn't going to cut it, either, for reasons I've already beat to death) or develop an alternative model that's also falsifiable. What characteristics of these stone holes indicate they weren't created for blasting rocks?

RSS Feed

RSS Feed