Debate about the authenticity and potential implications of the KRS has gone on semi-continuously since the stone was first reported in 1898 (you can read reviews of the history of the debate here and here, among other places). As I'm in the habit of using my blog to help me organize my research, I'll probably write posts as I work my way through the debate.

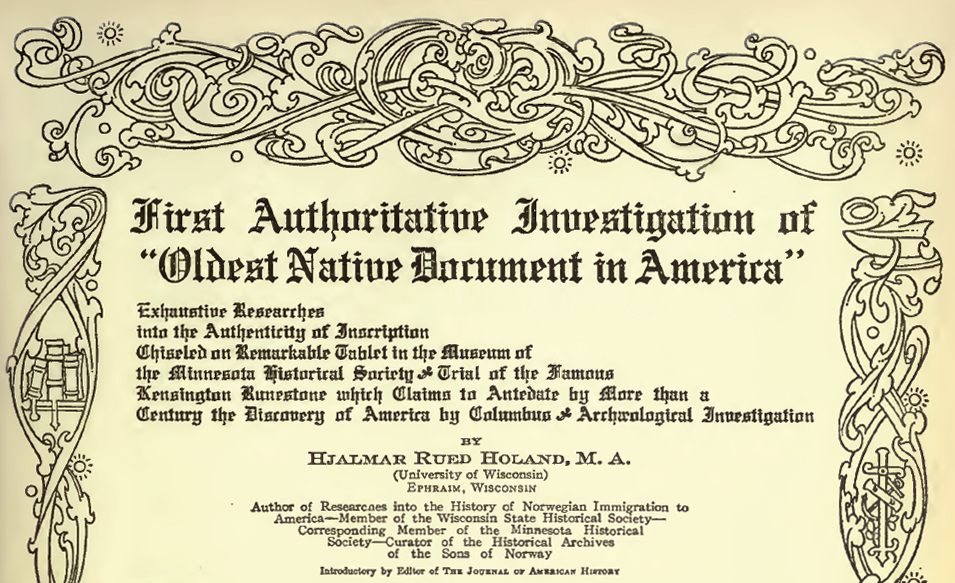

This morning I read through the 1910 article by Hjalmar Rued Holand in The Journal of American History (Volume 4, pp. 165-184, available here). The first thing that struck me was the title:

- Improbability: how could a Norse party have journeyed that far into the interior of North America and left only a stone?

- Runological correctness: are the runes and language on the stone "correct" for the mid-fourteenth century, or are they the work of a modern hoaxer?

- Material characteristics: are the features on the modified and unmodified surfaces of the stone consistent with creation of the inscription during the fourteenth century?

As an archaeologist, the "improbability" question is of greater interest to me than questions of runes or geology. Human behavior leaves material traces. If the KRS was produced by a fourteenth century European expedition (Holand goes so far as to specify who he thinks led the expedition), I would expect that there would be some tangible traces of that expedition in addition to a carved stone (remains of campsites? European goods incorporated into Native American economies?). Those traces are not likely to be easy to find, however: we can anticipate that the residues left by a small, rapidly moving expedition would be very difficult to locate. For the sake of comparison, consider the archaeology of early Spanish attempts to explore and colonize the Southeast. Hernando De Soto journeyed through the southeast in the mid-1500's with a small medieval army of about 600 people along with wagons, pigs, and horses. De Soto's group (much larger, I think, than the party that most people envision would have been associated with a proposed Norse exploration of the American interior) left a very faint archaeological signature. The location of the short-lived coastal colony of San Miguel de Gualdape, occupied by 500 people for a few months in 1526-1527, has yet to be identified. The Mississippian village of Cofitachequi, visited by the De Soto expedition in 1540 and the Juan Pardo expedition in the 1560's, has yet to be identified based on positive material evidence (although it almost has to be the Mulberry site). The location of Fort San Juan, the first interior Spanish settlement in the interior of North America, was only recently confirmed to be at the Berry site in North Carolina.

While the traces left by Spanish expeditions are light, they aren't invisible. Is it possible that definitive evidence of a Norse expedition into the interior (other than the KRS) would be so light as to fly under the radar despite a century of scrutiny? It's a fair question.

I admit that my first reaction as I start to learn more about the KRS is a bit of disappointment: has the debate over this artifact really remained so static over the last 100 years? I hope not. I also find myself asking what else there is to go on at this point. Despite what the popular media tell us, archaeology is not primarily a game of singular "discoveries" like the KRS. It's about patterns, multiple lines of evidence, and putting in the hard work to understand how the past human behaviors we want to understand relate to the material traces we can observe and study. If the KRS is genuine, it's hinting at a pretty interesting story. But it won't be the only piece of evidence that can tell the story. With the main points of argument about the KRS apparently still unresolved after 100 years, I'd spend some effort pursuing other avenues if I was looking for positive evidence of Norse expedition into the interior in 1362.

I think Holand's use of "native" hints at the context of his advocacy of the KRS. That doesn't, in and of itself, mean he's wrong about the stone, however. His paper mentions several things I plan to look into further. And so it begins.

RSS Feed

RSS Feed