If you're interested in military aviation history but you've never been to the USAF museum in Dayton, Ohio, you owe to yourself to get there at some point. As the official museum of the Air Force, they have access to a lot of unique aircraft that you just can't see anywhere else. I made my second visit today, specifically to visit the newly-opened fourth building housing the only XB-70 in the world. The "X" designation is given to aircraft that are experimental.

XB-70A in the National Museum of the Air Force, Dayton, Ohio.

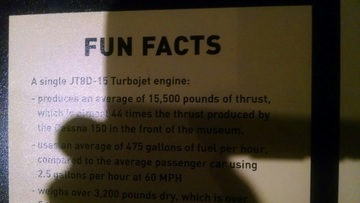

XB-70A in the National Museum of the Air Force, Dayton, Ohio. I've been fascinated by photos of the XB-70 since I was a little kid and it was a thrill to see it in person (I was delighted to find that many other unique experimental aircraft that I'd only ever seen in pictures were also on display in the new building -- really amazing). As a technological artifact, this vehicle marks the endpoint of the evolutionary trend of bombers going faster and higher. It was designed to fly at Mach 3 with a ceiling of 70,000-80,000 feet (depending on the source). Just over sixty years after the Wright brothers first flew their aircraft a total of distance of 120 feet at about 6.8 mph, humans had produced a flying machine that could surf through the stratosphere on its own shockwave at three times the speed of sound.

The chess game of military aviation took design in new directions after the 1950's, leaving the B-70 as a design that was strangely both ahead of its time but also obsolete. The B-52 (which the B-70 was supposed to replace) is still in service, and emphasis is on producing bombers that can fly low (such as the B-1B) and/or use stealth technology (such as the B-2) to avoid radar detection. The newly announced B-21 is a stealthy, sub-sonic design that aims to evade detection rather than outfly it.

I think the phenomenon of advanced "orphan" designs like the XB-70, produced at the very edges of technology but also not terribly useful, may be more common than we might guess. Technologies change, and once common ways of doing things often persist in niche roles. The "survivors" however, are not the most developed expression of a technology. I had a 1987 Dodge Colt, for example, that had a very complicated feedback carburetor. Fuel injection has replaced carburetors in automobiles, but carburetors are still used in numerous other applications. But neither my chainsaw nor my lawnmower has a feedback carburetor like the one on a 1987 Dodge Colt. I can think of other examples. The most "advanced" examples of technology occur not at the end of a technological tradition, perhaps, but at the "peak" of its use. Just a thought.

Tomorrow I'm hoping to see a perpetual motion machine from the Civil War. It's going to be hard to top finally getting to see the XB-70.

RSS Feed

RSS Feed