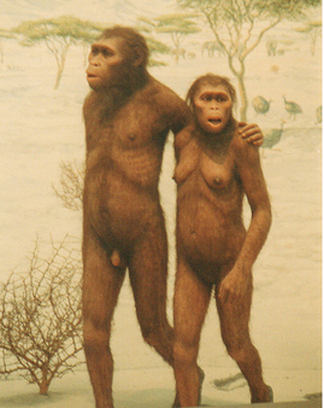

Depiction of male and female Australopithecines at the American Museum of Natural History.

Depiction of male and female Australopithecines at the American Museum of Natural History.

While I was reading one of the student papers from that class this semester, I started to question the model I had in my head of australopithecine females assisting each other in birth. The student wrote something that seemed to imply (intentionally or not - I'm not sure) that males were the ones giving assistance at birth. It struck me as odd, which made me ask myself why it should strike me as odd: why did I assume females and not males?

I don't think Rosenberg and Trevathan ever specify that females would have been the ones providing assistance to other females, but they use the term "midwifery" several times in their papers. Though not technically defined today as excluding males, the term "midwife" carries a lot of history that associates it very closely with females. This is the etymology as provided by Wikipedia:

"The term midwife is derived from Middle English: midwyf literally "with-woman", i.e. "the woman with (the mother at birth), the woman assisting" (in Middle English and Old English, mid = "with", wīf = "woman")."

Based on a quick perusal of some of the web resources that pop up first (e.g.,this, this, and this) the idea of the ancient origins of the association between females and birth assistance is widespread. I have no reason to doubt that this is correct: I would presume a strong female bias in birth assistance could be amply demonstrated both historically and ethnographically.

So should we assume that females were also providing birth assistance among early hominids?

Maybe not.

It seems clear that our modern conceptions of who should provide assistance at birth are culture-bound. By "culture-bound" I mean connected to other shared, leaned aspects of human societies, behaviors, and symbolic systems. I don't think I'll get an argument if I state that there is zero evidence for anything like human culture among australopithecines. So what happens to our gendered conceptions of birth assistance if you remove all or most of their cultural underpinnings? Would birth assistance still be performed primarily by females?

For the sake of argument, consider how selection might act to reinforce the behavior of males assisting females during birth. If labor and delivery are dangerous for both the female and the neonate, any assistance a male mate can provide increases the chances his genes will be passed on. This would be true in a situation of stable male-female pair bonding, as pair-bonding decreases the uncertainty of paternity. The inclination of males to provide effective assistance during birth would be selected for if pair-bonding was present and birth was dangerous.

If we assume that pair-bonding among australopithecines would not have been the same thing as "marriage" (a human cultural behavior), why do we assume that australopithecine birth assistance would be the same thing as "midwifery"? Our historical and ethnographic record of what humans do now really only gets us so far in addressing questions like this: the universality of a cultural practice among modern humans does not necessarily mean it always existed in the same form deep into the past.

RSS Feed

RSS Feed