|

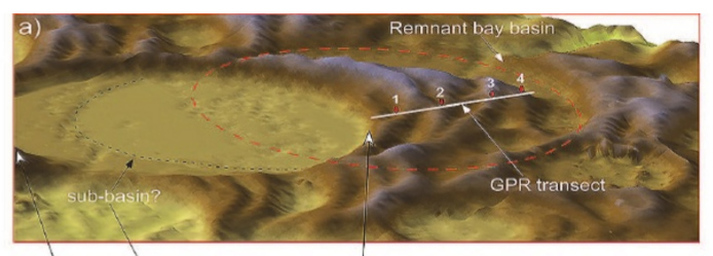

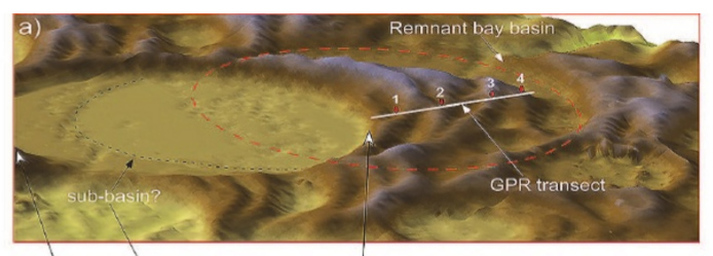

The post about the Carolina Bays that I wrote a couple of weeks ago turned out to be relatively popular (as far as this webpage goes, anyway). Carolina bays are elliptical depressions of varying size that occur along the Atlantic Coastal Plain in a band extending from New Jersey to Florida. Their limited geographic distribution and northwest-southeast orientation has given rise to many ideas about how these features were formed. Ongoing debate centers around the question of whether the bays formed as (1) the result of impacts associated with an extraterrestrial object (e.g., debris ejected by a comet strike in Saginaw Bay) or (2) through the actions of wind and water during the Pleistocene. Extraterrestrial or terrestrial? A new paper by Chris Moore and colleagues (see full reference below) in Southeastern Geology provides more evidence that the bays were formed and modified over long periods of time by natural, terrestrial processes. You can read the paper for yourself here. The analysis in the paper focuses on Herndon Bay, a 1-km long elliptical depression in Robeson County, North Carolina. Using a combination of detailed surface mapping, ground penetrating radar data, geomorphological analysis, and age estimates obtained using OSL, Moore et al. show that punctuated migration of Herndon Bay to the northwest from about 41 to 24 thousand years ago produced a sequence of sand rims on the southeast side of the basin. The bay held its shape and orientation as it migrated over the course of thousands of years.  A portion of Figure 3 from "The Quaternary Evolution of Herndon Bay, a Carolina Bay on the Coastal Plain of North Carolina (USA): Implications for Paleoclimate and Oriented Lake Genesis." The numbers show locations of dated sand rims left by migration of the bay (4 is the oldest, 1 is the youngest). The evidence and analysis that Moore et al. present is a pretty strong argument against the idea that the bays were formed by a single event (i.e., an extraterrestrial impact). I encourage you to take a look at the paper. I'll just paste in a paragraph from their conclusion (pg. 168): "The characteristics of Carolina bays, including basin shape, changes in basin orientation with latitude, and sand rims reflect long-term and pervasive environmental, climatological, and hydrological factors over millennia rather than from sudden or catastrophic events (Kaczorowski, 1977; Thom, 1977; Carver andBrook, 1989; Brooks and others, 1996; Grant and others, 1998; Brooks and others, 2001;Ivester and others, 2007, 2009; Brooks and others, 2010). The fact that practically all Carolina bays in a particular geographic region have nearly identical patterns of shape, orientation,and sand rim composition suggests similar processes working over long periods of time. This study also indicates that Carolina bays can respond rapidly, and appear to become more active during periods of climatic instability. While many nuances of bay evolution remain to be re-fined, the evidence at Herndon Bay clearly supports the concept that Carolina bays represent a regional example of a globally-occurring phenomenon: They are wind-oriented lakes shaped primarily by lacustrine processes." Reference: Moore, Christopher M., Mark J. Brooks, David J. Mallinson, Peter R. Parham, Andrew H. Ivester, and James K. Feathers. 2016. The Quaternary Evolution of Herndon Bay, a Carolina Bay on the Coastal Plain of North Carolina (USA): Implications for Paleoclimate and Oriented Lake Genesis. Southeastern Geology 51(4): 145-171. Addendum (3/18/2016): Let's start over with the comments. Please keep comments on the topic of the blog post (Carolina bays) or I'll delete them.

Last week I wrote a post about the 3.3-million-year-old pre-Oldowan stone tool assemblage reported from the Lomekwi 3 (LOM3) site in Kenya by Harmand et al. (2015). As I was writing that, I remembered a 2004 paper by Sophie A. de Beaune titled "The Invention of Technology" (Current Anthropology 45(2):139-162) that I had read in grad school. That paper takes a long-term view of the evolution of technology focusing on the development and proliferation of different kinds of percussion. Now that we have direct evidence of what kinds of stone tool technologies preceded Oldowan, I wanted to take another look at de Beaune's work. Her basic premise, if I understand it, is that one can create a "phylotechnical tree" of actions associated with different kinds of percussion. Following Leroi-Gourhan (1971), her use of the term "percussion" includes actions such as sawing, chopping, cutting, and puncturing. All of these different actions would ultimately have had a common origin in what de Beanue calls "thrusting percussion" (using one object to forcefully strike another with the intent of cracking or smashing it). The primacy of thrusting percussion is supported by its ethnographically-observed use among chimpanzees: some chimps crack hard fruits by smashing them between a hammer and an anvil. Thus, de Beaune argues, thrusting percussion would have been utilized by the earliest hominids and preceded the more formalized stone tool technologies we can recognize in Oldowan. How, why, and when did thrusting percussion, perhaps first used solely as an action employed to crack animal or vegetable materials, begin to be used to used to crack stone? Those are the questions that can potentially be addressed directly by the assemblage reported from LOM3 (and hopefully more to be found in the future). To the "when" question, LOM3 answers "by at least 3.3 million years ago." It's hard to imagine that the earliest identified example of something actually marks its earliest occurrence, so it's probably safe to presume that the behaviors that created LOM3 were present sometime prior to 3.3 MYA. The first publication on 149 pieces of worked stone from LOM3 also gives us some insight into the "how" question. According to the authors (pp. 311-312), the assemblage contains 83 cores (pieces of stone used for the removal of flakes) and 35 flakes. The remainder of the stone pieces are interpreted as "potential anvils" (n=7), "percussors" (n=7), "worked cobbles" (n=3), "split cobbles" (n=2), and indeterminate fragments (n=12). You can see 3D digital models of some of the artifacts here.  Core from the LOM3 site (image source: http://www.nature.com/nature/journal/v521/n7552/full/521294a.html) Core from the LOM3 site (image source: http://www.nature.com/nature/journal/v521/n7552/full/521294a.html)

The LOM3 cores are not small. The mean mass is 3.1 kg (6.8 pounds): that's heavier than a standard brick but lighter than your average bowling ball. The flakes, anvils, and percussors are large, also, compared to those from later Oldowan sites and from those in assemblages produced by wild chimpanzees (p. 313). Although some artifacts have a series of flakes detached, patterns of fracture and flake removal suggest to the authors that the "precision of the percussive motion was also also occasionally poorly controlled" (p. 313):

"The dimensions and the percussive-related features visible on the artefacts suggest the LOM3 hominins were combining core reduction and battering activities and may have used artefacts variously: as anvils, cores to produce flakes, and/or as pounding tools. . . . The arm and hand motions entailed in the two main modes of knapping suggested for the LOM3 assemblage, passive hammer and bipolar, are arguably more similar to those involved in the hammer-on-anvil technique chimpanzees and other primates use when engaged in nut cracking than to the direct freehand percussion evident in Oldowan assemblages." (p. 313) That sounds to me like a description that's pretty consistent with a manufacturing strategy based largely on chimp-like "thrusting percussion," and perhaps exactly what one would expect to precede Oldowan based on de Beaune's analysis. What about the "why" question? What caused hominids to start using thrusting percussion to produce tools? Answering that question is tougher than addressing the "when" and "how" questions. I don't think it has much to do with a change in physical anatomy -- specifically that of the hand -- for three inter-related reasons. First, as I discussed before, I think there's a lot of evidence that suggests that hands with the capacity for human-like precision gripping were widespread among early hominids, including the australopithecines of around 3.3 MYA. (See also this comment on australopithecine hands that just came out in Science today.) Second, as discussed by de Beaune (p. 141-142), the physical actions required to smash one rock with another are not all that different than the actions required to smash a piece of fruit on an anvil: no new anatomy was even required to shift the "target" of the percussion to stone. Third, even with the limitations imposed by their hand anatomy, chimpanzees can be taught to use freehand percussion to make stone tools (see this video of Kanzi, for example). If the "invention of technology" (meaning, in this case, chipped stone technology) wasn't dependent upon a change in anatomy, what about a change in cognition? Again following Leroi-Gourhan, de Beaune (2004:142) discusses the nature of the distinction between using a hammerstone to smash something to process food and hitting a stone with another stone to produce a cutting edge: "While these activities involved related movements, that of intentionally splitting a cobble to produce a cutting tools, although "exceedingly simple," was in [Leroi-Gourhan's] view eminently human in that it "implied a real state of technical consciousness."" Maybe there does have to be a cognitive change to explain the shift to producing and using stone tools. But, as we know from the Kanzi example, there's nothing lacking in the chimp brain that prevents them from making and use simple chipped stone tools when they're taught. But, as far as we know, they have to be taught (the last time I checked, though, humans also need to be taught to do it). Surely an important thing to understand about the shift to using stone-on-stone percussion to make stone tools is what that shift gets you: a tool with a cutting edge unlike anything that exists in nature. A sharp-edged flake can be used for what de Beaune calls "linear resting percussion" (cutting and chopping). You can do a lot of things with an edged tool that you can't do with a blunt one (and that you can't do with your teeth if, like australopithecines, you lack the large canines of chimps and many other non-human primates). You can sharpen a stick. You can grate and slice plants. And you can cut meat from bones and disarticulate an animal carcass by severing ligaments. We have some direct evidence of this last activity in the form of the 3.4-million-year-old cutmarked bones reported from Dikkika, Ethiopia, in 2010. Maybe the battlefield of the hunter-scavenger debate, now several decades old, will be reinvigorated by a transplantation from the Pleistocene to the Pliocene. Does the emergence of chipped stone technologies during the Pliocene signal an adaptive shift, a cognitive shift, or both? With the publication of the LOM3 tools and the announcement last week of a new fossil australopithecine from about the same time period and neighborhood, East Africa 3.3 million-years-ago sounds like a pretty interesting place to be. If, as suggested by ethnographic data from chimps, gorillas, and orangutans, the capacity to use tools is really a homology that extends deep into the Great Ape lineage, it's probably not fair to refer to the production of chipped stone tools as the "invention of technology." But it is a watershed nonetheless. The shift to using one set of tools (hammers and anvils) specifically to make other, qualitatively different tools (cutting implements) that potentially open up new subsistence niches and eventually (possibly) become involved in the feedbacks between biology, technology, and culture which are entangled in the emergence of our genus is something worth knowing about: who did it? why? what were the tools used for? what changed as a result? The assemblage from LOM3 opens up a tantalizing window on those questions. In those 149 pieces of stone, we have evidence of a stone tool production strategy that used "passive hammer" techniques to produce cutting tools, somewhere in time much closer to the dawn of stone tool production than anything called Oldowan. Judging by the size of the cores and flakes, the technique appears to have been more dependent on brute force than finesse. The results, however -- the creation of cutting tools from a natural setting that provided none -- may have been transformational. I look forward to seeing how the data from the small LOM3 assemblage get incorporated into models of human evolution, and I hope that people working in East Africa are already busy finding more sites. And I hope that people working outside of East Africa are actively searching for stone tools in Pliocene deposits. It's a great time to be following paleoanthropology.

de Beaune, S. (2004). The Invention of Technology: Prehistory and Cognition Current Anthropology, 45 (2), 139-162 DOI: 10.1086/381045

Harmand S, Lewis JE, Feibel CS, Lepre CJ, Prat S, Lenoble A, Boës X, Quinn RL, Brenet M, Arroyo A, Taylor N, Clément S, Daver G, Brugal JP, Leakey L, Mortlock RA, Wright JD, Lokorodi S, Kirwa C, Kent DV, & Roche H (2015). 3.3-million-year-old stone tools from Lomekwi 3, West Turkana, Kenya. Nature, 521 (7552), 310-5 PMID: 25993961

Leroi-Gourhan, A. (1971). L'Homme et la Matiere. Paris: Albin Michel.

|

All views expressed in my blog posts are my own. The views of those that comment are their own. That's how it works.

I reserve the right to take down comments that I deem to be defamatory or harassing. Andy White

Email me: [email protected] Sick of the woo? Want to help keep honest and open dialogue about pseudo-archaeology on the internet? Please consider contributing to Woo War Two.

Follow updates on posts related to giants on the Modern Mythology of Giants page on Facebook.

Archives

January 2024

Categories

All

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed