- An abstract at the top of the page;

- Occurrence dates, Sword numbers that correspond to the entries in the Fake Hercules Sword database, and provisional type designations;

- Blade similarity indicator arrows and annotation for Type F;

- Indicator lines and annotation for similar "clean blade" versions (possibly Type CS);

- Indicator lines and annotation for the single "Pugio" (Type P) example;

- Enhanced pinstripe.

|

Peter Geuzen, Fake Hercules Sword enthusiast and Friend of #Swordgate, has produced an updated version of his poster that includes additional information and comparisons. Here it is:

Changes from Version 3 include:

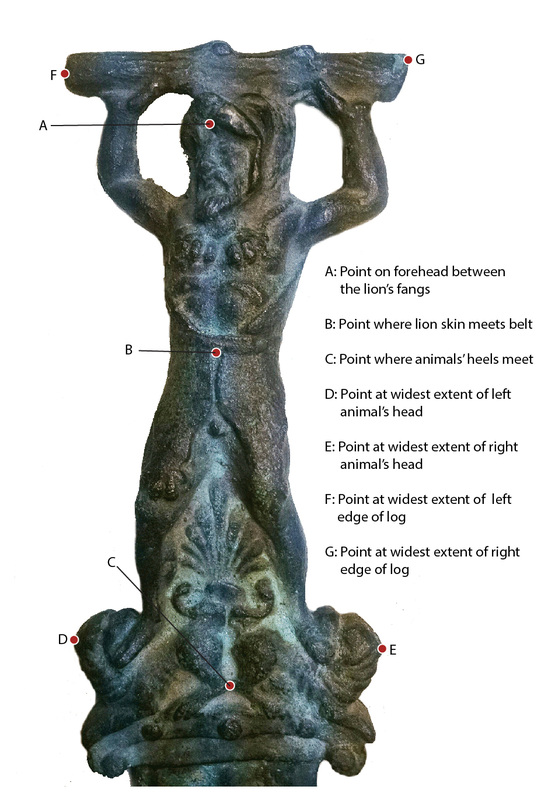

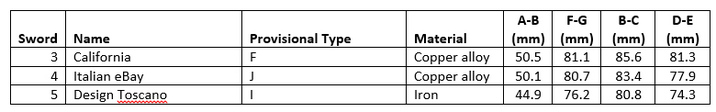

One of the things that's made #Swordgate fun is the online interactions I've had with people who are interested in the swords in particular, pseudo-archaeology in general, ancient Rome, the history/prehistory of Nova Scotia, The Curse of Oak Island television program, and any and all combinations of those things. Science is a human endeavor. In this case, the human component has been just as rewarding to me as making progress in cracking the problem. I've really enjoyed interacting with Nova Scotians who have a genuine interest in the cultural heritage of their province. I've gotten a lot of encouragment from them, and that has helped to keep me going. The people who send me messages, write me emails, and comment on this blog tell me that the issues involved in Swordgate matter to them on several levels. They are interested and engaged, and the story matters to them. I wanted to pass along this video by a Nova Scotian giving his point of view of what's been going on. If you're wondering what people on the local and regional level think of all this, his words will provide you with a good data point. It's not just an academic issue of whether the sword (or any of the other pieces of "evidence" being put forward) is authentic or not. It's about more than that. Watch the video if you've got 15 minutes. (Fair warning: there's a little bit of language -- nothing worse than what your kids have probably already heard if they've graduated the fourth grade). I want to thank everyone for the comments and links related to shrinkage during during the metal casting process. I apologize for not having time to respond to the comments or investigate the sources thoroughly at this point. The take-away point I'm getting is that size decrease is inevitable during metal casting. A given mass of metal will have a greater volume when molten then when solid, so the metal piece that is produced from a mold will be smaller when cold than the mold it filled up when molten. There is also the potential for molds made of ceramic to shrink while when they are produced. Anyway, it appears that it's perfectly logical to expect a trend of decreasing size if a series of objects that was produced through a "chain" of copying. The first generation will be smaller than the original; the second generation will be smaller than the first, etc. The sources several of you provided suggest about 1-2% size difference between the mold and the cast is typical of copper alloys. I took a few minutes and gathered some metric data from the three swords I've got in my office (California, Italian eBay, and Design Toscano). I defined seven landmarks (labeled A through G on the diagram) that I could reliably locate on all three swords. I used dial calipers to measure the straight line distances between four pairs of landmarks. Here are the raw data: The larger size of the Hercules on the California sword shows up in all the dimensions. The Design Toscano sword in the smallest. The Italian eBay sword is in-between. That supports a chronological ordering with the California sword earliest, the Italian eBay second, and the currently-produced Design Toscano sword latest. If these three swords represent different generations, how much size decrease was there between generations? I calculated the differences (in both millimeters and percentages) of the measured dimensions of two pairs: (1) the California sword (Sword 3) and the Italian eBay sword (Sword 4); and (2) the California sword and the Design Toscano sword (Sword 5). Here are those data: The measured dimensions vary from 0.8% to 4.2% between California and Italian eBay, with a mean difference of about 2%. To me, that seems most consistent with California and Italian eBay being representatives of sequential generations. Maybe the generation of the J Type swords was just once removed from the generation of the F types (in other words, an F Type sword was used as the model for the J Type, replacing the partially fullered blade with a shorter, unfullered blade).

The differences between the California sword and the Design Toscano Sword vary from 5.6% to 11.1%, with a mean of about 7.8%. Assuming a 1.75% decrease in size per generation, the Design Toscano sword could be fifth or sixth generation (with the California sword being "Generation 1"). A fifth generation sword would be expected to be about 93% the size of a first generation sword, assuming each generation is 98.25% the size of its parent. I think the Cvet sword, the Spain sword, and the sword currently for sale on eBay (from Florida) could be members of a generation between the Italian eBay sword and the Design Toscano swords. These swords appear to be copper alloy swords with relatively "clean" blades missing the suite of anomalies that we're using to define the J Type. I've been calling this grouping "Type CS" in my head. If my hypothesis is correct, the dimensions of the Hercules on the Cvet sword should fall between those of the Italian eBay sword and the Design Toscano sword. This is just a quick post to show you a first-time-ever, in-person lineup of three of the provisional types of Fake Hercules Swords. The Italian eBay Sword (aka Sword 4 in the Fake Hercules Sword Database) owned by Trevor Furlotte arrived at SCIAA today to much fanfare. I taught class this morning until 9:45. When I got to my building after that I was immediately told that a box had arrived. Three PhDs watched me open the box and we got to do a quick visual comparison between the Italian eBay sword, the California sword, and the Design Toscano sword. Then everyone went about their business for the day, including me. I'm looking forward to having a careful look at the Italian eBay sword when I get a bigger block of time. But I wanted to share one quick observation. If I've correctly surmised that the various types of swords we've defined have a chronological significance (with Type F [California] being earliest, Type I [Design Toscano] being most recent, and Type J [Italian eBay] being somewhere in the middle), it appears that there may be a trend of decreasing size of the Hercules figure through time. Look at this image of the sword hilts lined up against a straight edge: Hercules gets shorter from left to right, which is what I think is an earliest-to-latest time ordering of these things. I had already noticed that the Design Toscano Hercules was smaller than the California Hercules, but I hadn't even thought about how the Type J would compare.

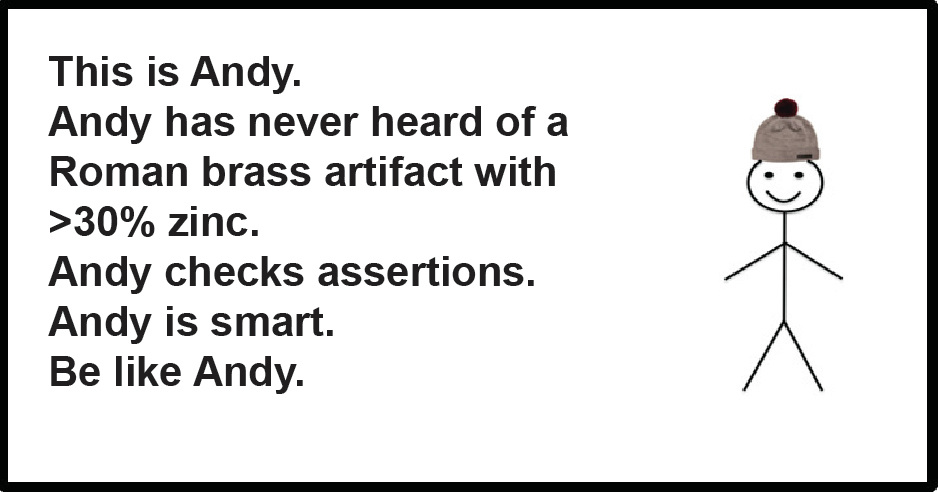

A decrease in overall detail from left to right is also noticeable in the line-up. I'm not sure exactly how to explain the decrease in size, but it is intriguing. In craft traditions, a decrease in size through time of stylistic elements (i.e., parts of the design that are not stongly constrained by functional requirements) could be expected to be the natural result of accumulations in copy error. Generally, humans can't reproduce something exactly correctly by hand -- there's typically a +/- 5% error that isn't noticeable to the human brain or controllable based on our abilities. (Some researchers contend that a decrease in mean size is the expected outcome of accumulated copying error -- I've played around with that in some of my modeling work and found that the median drifts downward rather than the mean, but that's not super relevant here and it's been a long time since I thought about it.) But why would there be a trend toward decrease in size over time when a mold is used? I'm not sure why that would be, but it's interesting because it seems consistent with some kind of copy chain (i.e., copies made from copies) rather than copies made by reference to some original. I'll have more to say about this later when I have some time to take a close look at all of these and fill in some blanks in the database. I don't quote Ronald Reagan often, but brace yourselves because I'm going to quote him now: "There you go again." Reagan delivered that line in an exchange with Jimmy Carter in a presidential debate in 1980. He said it following a laundry list of claims by Carter about Reagan's stance on healthcare issues, famously dismissing what he regarded as a bunch of inaccurate nonsense. Most of the latest temper tantrum of inaccurate nonsense delivered to the world by demonstrated liar, accomplished plagiarist, and former Facebook user J. Hutton Pulitzer can be just as easily waved off as foot stomping that is not relevant to the "evidence" that he has put forward to support his claim of an ancient Roman visit to Nova Scotia. There is one point I wanted to discuss, however, that relates directly to misinformation about the Nova Scotia sword. In her analysis of the sword, Christa Brosseau found the copper alloy used to make the sword to be 35% zinc. The high level of zinc (indicating a modern brass) was one of several observations that led Brosseau to conclude that the sword was probably manufactured sometime after 1880. Brosseau wrote that "a brass that is being put forward as ancient which contains a zinc content greater that 28% is suspicious." In his post, Pulitzer seems to be claiming that ancient Roman artifacts commonly had levels of zinc in the 35% range. He writes: "With the Thomas Jefferson National Accelerator Facility — Office of Science Education specifically citing that a zinc level of 28% falls almost exactly in the middle of the range PROVEN to be both Roman and up to 2,500 years old, who does one trust?" When dealing with Pulitzer, the safe answer to the "who does one trust" question is always the same: not Pulitzer. The webpage he links to does indeed say that copper alloys classified as brass contain between 5% and 45% zinc. It says the Romans made brass, but it does not say that the Romans made high zinc brass. They did not. I'll back up my statement with a couple of quoted references (thanks to my readers for pointing these out), and then finish off my discussion of Pulitzer's characterization of Roman brass with a helpful meme. Here is quote from "A Roman Late-Republican Gladius from the River Ljubljanica," a 2000 paper by Janka Istenic: "The majority of Roman fresh cementation brasses, unadulterated with scrap bronze, seem to contain about 20% of zinc, little lead, and a small amount of tin (cf. Jackson, Craddock 1995, 93; Craddock, Lambert 1985, 164)." Here is what is says about Roman brass on Wikipedia, which one would think would be an easy enough source to consult: "Brass made during the early Roman period seems to have varied between 20% to 28% wt zinc.[71] The high content of zinc in coinage and brass objects declined after the first century AD and it has been suggested that this reflects zinc loss during recycling and thus an interruption in the production of new brass.[72]" Finally, there is a 2006 paper ("Neutron Activation and X-Ray Fluorescence Analyses of Early Roman Age Bohemian Artifacts") that I saw bandied around Facebook with some excitement because those reading it thought it indicated that some Roman brass contained up to 85% zinc. They were referring to Table 2, apparently, which they were reading wrong: the table shows only one entry for an artifact with a zinc level above 26%. The "85.7" in the Zn column under "Drinking Horns" is saying that 85.7 percent of the drinking horns in the sample have 0-2 percent zinc. There is no evidence of which I'm aware of Roman brass with a zinc content greater than 30%. That means there is no evidence that the metals in the Nova Scotia sword could have been made in ancient Rome. It's interesting to note that Pulitzer's attempts to discredit the testing of the sword have now moved from claiming a conspiracy to fake the results of the test (by swapping swords) to claiming that Brosseau's results are in line with what we expect of ancient Roman brass. This is not an insignificant shift, as he is basically admitting that his XRF results (which he still has not described in detail) are garbage compared to what Brosseau produced. I have a feeling he looked at Brosseau's summary of her analyses and realized there was no longer a path for him to claim that his alleged testing was somehow "superior" to hers. So now's he's left having to argue that the Romans could have indeed made that metal. Good luck with that argument - it's not a winner. Roman brass with 35% zinc? There you go again . . .

Peter Geuzen has produced an updated version (3.0) of the #Swordgate poster that includes all twelve of the known Fake Hercules Swords. Perhaps the mystery will be solved with the thirteenth sword is found . . . cue the dramatic music.

I hope to find time soon to update the Fake Hercules Sword database and update the Argumentative Archaeologist pages with the latest posts on the sword, the "crossbow bolts," and the Harold Stone. I'll probably create "Oak Island" and "Roman Scotia" pages there to organize all the information. I'm also going to create a distinct area on this website to organize posts about the various swords - there's a lot of information about them now and I can make it easier to find. I've got a lot to do today and probably won't be able to squeeze all of that in, but it's coming.

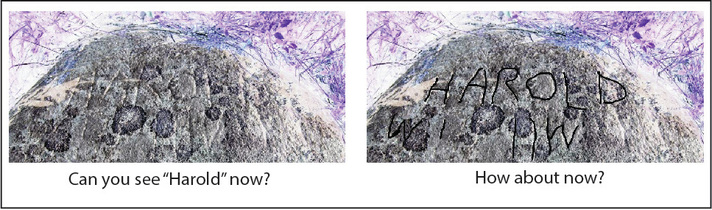

The latest weak coffee to be added to stew of "evidence" for a Roman occupation of Nova Scotia is a "Roman inscribed stone." The carved boulder, described in this post as a "Roman symbology stone," joins an evidence list that already includes such powerhouse "smoking guns" as a modern brass tourist sword and some "crossbow bolts" that are most likely pieces of historic period logging tools. The "Roman symbology stone" is depicted as covered with all kinds of symbols that don't look like much to me. Apparently you have to be a professional cacheologist to understand that the symbols on the stone mark "some form of a Roman Recon Mission, possibly a forbearer to various Iberian Reconquistas hit the shores of Oak Island." Or, as Howard Montgomery (an alert member of an Oak Island group on Facebook) did, you could just turn the stone upside down and read it as it was meant to be read. It says "Harold." These pieces of "evidence" seem to be getting dumber and dumber, which (hint hint) is the wrong direction to go if you want to build a case that anyone will take seriously.

Recently I've been asked how long I plan on staying on this topic. I don't really have an answer to that except to say that I'll write about something if it interests me. I found #Swordgate to be fascinating, so I put quite a bit of effort into it. The drivel that we're seeing now, while somewhat entertaining in a strange way, doesn't have much appeal to me beyond the "how long does this go on" question. I'm curious to see how all this plays out now that (1) the main piece of "evidence" has been pretty thoroughly examined and (rightfully) thrown in the garbage pile and (2) the main proponent of the case has demonstrated himself to be less than credible both in terms of his interpretations and his statements of fact. Lately we've seen a second round of attempts to get the "Roman" story in the media. My impression is that those attempts have been less successful than the first round. We've also seen some kind of strange battle on social media that has apparently resulted in Pulitzer being suspended from using his Facebook accounts. One thing that I haven't seen yet is others in the "fringe" community distancing themselves from this debacle. As someone commented on my blog (sorry - I haven't been able to find the post again), what we're seeing here has moved beyond "fringe" archaeology into the realm of "tassel" archaeology. I get emails from people across the spectrum on things like this. One person who self-identified as someone on the "fringe" told me that "everyone on the fringe side is laughing at Hutton as much as the archaeological community." As far as I know, however, no-one on the "fringe" side has publicly said "enough of this nonsense." People who carefully read what I write will know that I am open to many different ideas about the past. I am a scientist, however, and for me to accept a claim as credible there has to be some kind of evidence that stands up to scrutiny. I think many of you on the "fringe" side understand and appreciate that and also understand that what we're seeing here does not meet even the minimum thresholds of quality of evidence, sincerity of investigation, or honesty of argument required to be taken seriously. The Ancient Artifact Preservation Society went all in on Pulitzer's story, and is apparently still backing all of this. Some of you could do a lot for your own credibility, I would suspect, by weighing in with your judgement of the merits of what's going on. Pulitzer is pretending to speak for all of you right now, and what he's saying is not making you look good. That's just my opinion. If you want to keep drinking the weak coffee and pretending it tastes good to you, that's your business. Prepare yourselves for some pretty bad tasting stuff coming down the road: my impression is that the coffee is only going to get weaker. Don't say I didn't warn you when we're debating a Little Caesar's box washed up on shore (that's from another blog comment that I can't find - sorry for stealing it to whoever said it) and you're still letting the TreasureForce Commander speak for you. The stone says "Harold." What else are you waiting for? This is just a quick not to point you in the direction of the latest addition to the Fake Hercules Sword club: the Cvet sword (it will become Sword 12 in the Fake Hercules Sword Database). It is another copper alloy sword that I think is probably similar to the Spain sword (Sword 7) and the Florida eBay sword (Sword 10) -- it has a relatively short, unfullered blade that is missing the casting anomalies present in the Type J swords.

I also give you another cartoon from Killbuck, which pretty much sums it up. The "sword" episode of The Curse of Oak Island aired in Canada last night, and Dr. Christa Brosseau is now free to discuss her analysis and results. In the period of time between now and when those of us in the U.S. got to see the episode, I've seen many incorrect (and, frankly, insulting) statements about Brosseau's work coming from those who have staked all their credibility on the sword being an ancient Roman artifact. We owe her a "thank you" for participating in this endeavor. I am very happy that Brosseau has agreed to let me publish this statement here. I'm sure that many people who will read this are not experts in metals analysis. Brosseau is. Even if you don't understand every detail of this summary, take note of the manner in which she describes the rationale for the tests she undertook, her methods, the equipment that she used, and her results. That's what professionals do. Brosseau tells me that she has been following this blog with interest, and will try to answer questions posed to her here. Have a question about the analysis after reading what she has to say? Fire away. I especially welcome serious questions from people who still "believe" in the sword. Insulting nonsense comments will be deleted. Here is what Brosseau sent me: Executive summary:

A metal sword was brought in for chemical testing during the summer of 2015. Objectives included determining if the sword was bronze or brass, and whether or not the chemical constituents could be ascertained, both qualitatively and quantitatively, in an effort to date the artifact. Both elemental and molecular testing was conducted. The chosen tests included scanning electron microscopy (SEM), energy dispersive x-ray spectroscopy (EDS), confocal Raman microscopy and surface enhanced Raman spectroscopy (SERS). Multiple samples of both the patina, as well as the base metal were taken from the tip of the sword. A sample of the base metal was also taken from the hilt to test the alloy composition. Two samples of an “added layer”, present on the front of the hilt was also taken for analysis. After chemical testing and analysis, the results conclude that this object represents a modern leaded brass with an artificial patina with a likely earliest manufacture date of ~1880 AD. The added layer is a lead oxide putty, applied for an unknown reason. Introduction: The determination of the chemical composition of copper alloys can be important in the dating of art historical objects formed from such alloys. Brass (Cu/Zn alloy) and bronze (Cu/Sn alloy) constitute the vast majority of copper alloys of interest since antiquity. In this analysis, two questions were put forward: (1) Is this sword a bronze or a brass and (2) Can the elemental composition of the base metal and/or the chemical constitution of the patina offer any clues as to the age of the object. The answer to the first question is readily provided in a standard elemental analysis. A zinc content above trace levels, and the absence of a significant amount of tin would suggest a brass. For brasses, the zinc content is a powerful indicator of chronology.1 The first functional brasses were produced by the Romans, and were prepared using a process wherein a zinc ore was reacted with copper metal at high temperatures. This smelting process occurs at temperatures of at least 1100°C, which is above the boiling point of metallic zinc. Thus, most of the zinc is lost to evaporation, putting a thermodynamic limit on how much zinc can be incorporated into a brass using this method. This upper limit is widely agreed upon to be 28%, based on the analysis of a multitude of early brasses, as well as more recent experiments aimed at recreating this early method.1 Therefore a brass that is being put forward as ancient which contains a zinc content greater that 28% is suspicious. This is especially true if the alloy has greater than trace amounts of lead or tin, which inhibit absorption of zinc in the alloy. In post-Medieval Europe, a more sophisticated cementation method was developed, which allowed the incorporation of more zinc into the alloy, up to 33%.1 Hence, dating from about the sixteenth century, some brasses have been found containing up to 33% zinc. Zinc content above this level is reflective of a more modern brass, produced using a more modern direct method (speltering), the patent for which was taken out in 1738 in Britain.2 The older cementation method was largely abandoned by the mid-1800s. While the zinc content is the most important element used to date brasses, other factors will be important as well, including a determination of the relative purity of the alloy (which might suggest a modern refinement) and the presence of modern pigments and/or resins will also be key indicators of modern manufacture. Methodology: The following chemical analysis tools were utilized in this study: 1. Scanning Electron Microscope (SEM) – TESCAN MIRA 3 LMU Variable Pressure Schottky Field Emission Scanning Electron Microscope This electron microscope provides micro and nanoscale resolution of a sample. Features such as slag in the metal and grain boundaries in the patina can be elucidated. 2. Energy Dispersive X-ray Spectroscopy (EDS) – INCA X-max 80mm 2 EDS equipped with silicon drift detection (SDD) The EDS unit is coupled to the SEM, and allows one to determine the elemental make- up of a particular region in the sample down to ppm levels. In this method, the sample is bombarded with a high energy electron beam, which excites core electrons in the sample. Upon decaying back to the ground state, energy is released in the form of x-ray radiation, which is monitored. The energy of these emitted x-rays is very specific to an individual element, and thus an elemental map of the sample can be obtained. This technique is akin to x-ray fluorescence (XRF), with a few notable differences. XRF can be used in a portable fashion, but this only allows for investigation of the surface of an object. In addition, portable XRF typically lacks the sensitivity and accuracy of EDS. When destructive analysis is possible, EDS is preferred. This will be used to determine the elemental composition of both the base metal and the patina. 3. Confocal Raman Spectroscopy – This instrument combines a confocal microscope with a Raman spectrometer, and provides a vibrational signature of the sample, such that the molecular species can be identified. This technique is based on light scattering. This will be used to evaluate chemical components of the patina that are Raman active, most notably any additives, resins or dyes/pigments. 4. Surface Enhanced Raman Spectroscopy (SERS) – This technique uses a thin layer of noble metal nanoparticles (Ag) over the surface of the sample, such that a much greater Raman signal can be obtained. This technique is particularly useful for samples which exhibit intense fluorescence, which can quench the Raman signal, or where the concentration of analyte is very low. This will be used to evaluate chemical components of the patina. Sampling and preparation of samples for analysis: For this analysis, several samples of the sword were collected for analysis. In each case the sample size was ~1-10 mg. Tip of sword: base metal filings, patina flakes Hilt of sword: base metal filings, patina flakes Hilt of sword: added layer of unknown origin (this was applied to a few areas of the sword, for an unknown reason) The patina flakes and the added layer were removed directly using tweezers. For the base metal, a small part of the sword was polished free of patina to expose the un-corroded metal, cleaned with solvent, and then several filings were taken using a steel file. Samples of the base metal of the hilt were taken at a later date in order to confirm the sword was one continuous metal. For the SEM-EDS the samples were prepared by the SEM technician on carbon tape studs. For Raman spectroscopy, the samples were analyzed directly on glass coverslips. For SERS, the samples on microscope slides were treated with a layer of silver nanoparticles prepared in house according to an established protocol.3 Results and Discussion Metallurgical analysis of the base metal: SEM-EDS analysis was conducted on the base metal filings. It was noted that the zinc content in this alloy is very high, at 35% ± 1% at 95% confidence, and thus is representative of a modern brass. This places the earliest manufacture date for the piece at 1738. In addition, the lead content is very high (2.6% ±0.7). Closer examination of the metal showed bright regions, referred to as slag. In this region the heavy metals (Pb, As, Sb, etc.) are typically co-localized. EDS analysis of the slag however showed only lead, suggesting that the lead is of high purity, and thus likely refined. Also, the copper itself is quite pure, with only very trace amounts of contaminants (As (one sample only), Sn, etc.) detected. Thus the copper itself is also likely refined. Electrowinning of metals was first demonstrated in 1847, and the practice was first patented in 1865.4 Commercial plants for electrowinning of copper ore existed in 1870 in Wales and in the early 1880s in the USA.5 Thus, the likely actual earliest manufacture date for this brass is 1870-1880. This sword constitutes a modern leaded brass. The lead would have been added to facilitate casting and to improve the strength of the alloy, and also to reduce corrosion. Metallurgical analysis of the added layer: In several places on the sword, an added layer was noted. This layer had a metallic lustre and was putty-like in nature. Results confirm this as a lead oxide, likely a lead white putty. The reason for this added layer is unclear; it may have been added to simulate a lead overlay or to hide an area where a defect in casting was present. Morphological and Elemental analysis of the patina: The patina was examined using SEM-EDS. This allows one to monitor the morphology of the sample, and obtain the chemical composition for a desired area of interest. While the samples were not prepared in cross-section, it is still evident that the patina is uniform in structure and morphology, which points to an artificial rather than natural patination process. Also, the patina was very easily removed, which also suggests an artificial patination. The patina in general, is fairly complex, however the chemical composition is dominated by copper, oxygen and chloride. This suggests the patina is mostly a copper hydroxychloride. The source of the chloride would be from either salt water corrosion, or from chemical patination using chemical reagents, for example chloride salts such as CuCl2 or NH4Cl. Since the extent of corrosion is limited, the latter explanation is the most likely. In addition, the patina contains iron and sulfur, which may also indicate chemical patination, through the use of CuSO4, Fe(NO3)3 or Na2S2O3, all commonly used reagents for brass patinas. In order to further evaluate the patina further at the molecular level, Raman spectroscopy and SERS was performed. Molecular Analysis of the Patina: The patina sample was evaluated using Raman spectroscopy, to ascertain the chemical make-up of the patina. Raman spectroscopy is particularly sensitive to substances which have the ability to scatter light well, through the presence of heavy atoms, or through the presence of electrons which are delocalized. Thus, it is an excellent method for the analysis of both inorganic and organic pigments. In this case, we were interested in determining whether any pigments might have been used to produce the patina. In several places, the recorded Raman signal was an exact match for Prussian Blue, a modern blue pigment. Prussian blue was first available for use in Europe in the early to mid-1700’s, and was in extensive use for the next several hundred years. The use of Prussian blue for the restoration of historical bronzes has been noted in several conservation publications, including the restoration of bronzes from the Fonderia Chiurazzi in Naples.5 The identification of Prussian blue in the patina strongly suggests that the patina is of modern origin, post-1734 AD, and was produced artificially. To conduct further analysis, SERS was performed. In this method, a thin layer of silver nanoparticles is applied to the surface of the sample, such that the Raman signal can be increased significantly. The SERS data identified multiple pigments in the same sample. Prussian blue was again identified, along with lead white and what appears to be a good match for Cerulean blue. Cerulean blue was first available for use in Europe in 1821. In addition, strong peaks in the region of 1500 cm-1 suggest the presence of a synthetic organic pigment, likely a yellow azo dye, which would be of 19th or 20th century manufacture. Peaks at 2800-3000 cm-1 due to the C-H stretching vibrations of organic materials are also suggestive of this. The likely presence of Cerulean blue and an unknown synthetic organic pigment suggest the sword was manufactured post-1820 AD. Conclusions: The Oak Island sword represents an out-of-place artifact with no established provenance. In this case, scientific analysis of the object can aid in answering some fundamental questions regarding the piece, such as the nature and composition of the alloy. In this case, it was determined that the alleged Roman sword is in fact a modern leaded brass with an artificial patina. Based on the materials analysis, this sword had to have been manufactured post-1738, and more likely post-1880, based on the materials and process of manufacture used. References: 1. P. Craddock. “Scientific Analysis of Copies, Fakes and Forgeries”. Elsevier, Oxford, UK, 2009. 2. J. Day. “Copper, Zinc and Brass Production” in J. Day and R. F. Tylecote, The Industrial Revolution in Metals, Institute of Metals, London, 1991. 3. “Surface-Enhanced Raman Spectroscopy: A Direct Method to Identify Colorants in Various Artist Media” C.L. Brosseau, K. Rayner, F. Casadio, C.M Grzywacz, R.P Van Duyne. Analytical Chemistry, 2009, 81(17) p.7443. 4. “Copper Leaching, Solvent Extraction and Electrowinning Technology” Ed. J.V. Jergensen II, 1999. 5. “The Restoration of Ancient Bronzes: Naples and Beyond” Ed. E. Risser and D. Saunders. J. Paul Getty Museum, Getty Publications, 2013. Additional Notes:

The story about claims for a Roman visit to Nova Scotia continues to get sillier. With the "100 percent confirmed Roman sword" that started this debacle over a month ago now 100 percent debunked by both our work on this blog and the metallurgical results summarized on The Curse of Oak Island, focus on the sword has been supplanted by conspiracy claims, a new "smoking gun" piece of evidence, and some kind of bizarre war being waged on social media. This intent of this post is simply to bring you up to date about what's going on.  The California sword. The California sword. The Sword(s) I would like to see the mystery of the Fake Hercules Swords solved. Even though they're not Roman, I still find them a fascinating problem. Who started making these things? What was the "original"? How and why did they change through time? I think I find this to be an interesting challenge because historic data seem to be few and far between, requiring that we address these questions through archaeological methods and techniques: build an assemblage, try to understand and organize variability, gather information about the intrinsic characteristics of the items, construct and test hypotheses, etc. To that end, I began a Fake Hercules Sword database yesterday, and I started a group on Facebook to keep a line in the water there. In other sword news, I will have a statement from Dr. Christa Brosseau to publish on this blog first thing Monday morning. (Update 1/25/2016: here is Brosseau's summary.) Dr. Brosseau will be able to speak publicly about her analysis after the "sword" episode of The Curse of Oak Island airs tonight in Canada. She has indicated to me that she's been following this blog and will try to respond to questions here.  Disassembly of antique Peavey, showing the spikes that could, if you really want to be silly, be mistaken for Roman crossbow bolts (used with permission of Oak Island Compendium). Disassembly of antique Peavey, showing the spikes that could, if you really want to be silly, be mistaken for Roman crossbow bolts (used with permission of Oak Island Compendium). Boltgate, We Hardly Knew You The new piece of "smoking gun" evidence for a Roman visit to Nova Scotia wasn't much of a mystery and didn't last long. The "Roman crossbow bolts" that were featured to us in the latest laundry list of nonsense turned out to be modern logging tools called Peavey points. This one was quickly cracked by Nova Scotians who understand what the remnants of their own material culture look like. Have a look at this post, this post, and this one from Oak Island Compendium. I feel pretty comfortable saying that the most plausible explanation for the "crossbow bolts" doesn't have anything to do with ancient Rome, Iberia, a 1000-year-old tree, a U.S. military testing lab, and a conspiracy to hide the truth. Don't rewrite your history books just yet: the "crossbow bolts" are pieces of logging tools. So much for Boltgate. I Just Assumed We Had All Graduated From Third Grade

As more pieces of the "evidence" for the Roman occupation of Nova Scotia have failed to stand up to scrutiny, we've been treated to a bizarre online temper tantrum that has included some person or group of people trying to disrupt various Oak Island groups on Facebook by creating fake profiles, reporting pictures as containing nudity (when they don't), and who knows what else. In a blog post on Friday, J. Hutton Pulitzer revealed that Facebook has apparently placed him on Double Secret Probation until Monday. He adds Facebook to the growing list of conspirators (e.g., academics like me, the Catholics, the media, The History Channel, etc.) that are trying to keep the world from knowing the truth about modern Fake Hercules Swords and logging tools that have allegedly been found in Nova Scotia. This is all very juvenile and has nothing whatsoever to do with an objective assessment of the quality of the "evidence" that's being put forward. I'm going to stay out of the nonsense as much as I can and stick to looking at the nuts and bolts (I wonder how long will it be until we are actually shown a picture of nuts and bolts and told they're Roman). Complete insulation from the idiocy, unfortunately, may not be possible. Certainly these shenanigans are actually a part of the story: the case of #Swordgate makes it clear that battles over ideas, evidence, and opinions are multi-leveled and occurring in many different ways and places across the internet. I have neither the time nor the appetite to fight them all, and I'm not planning on getting drawn into silly playground squabbles that will make no difference to the outcome. The arguments matter, sure, but my arguments are going to be based on things that are relevant to the questions at hand. |

All views expressed in my blog posts are my own. The views of those that comment are their own. That's how it works.

I reserve the right to take down comments that I deem to be defamatory or harassing. Andy White

Email me: [email protected] Sick of the woo? Want to help keep honest and open dialogue about pseudo-archaeology on the internet? Please consider contributing to Woo War Two.

Follow updates on posts related to giants on the Modern Mythology of Giants page on Facebook.

Archives

January 2024

Categories

All

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed