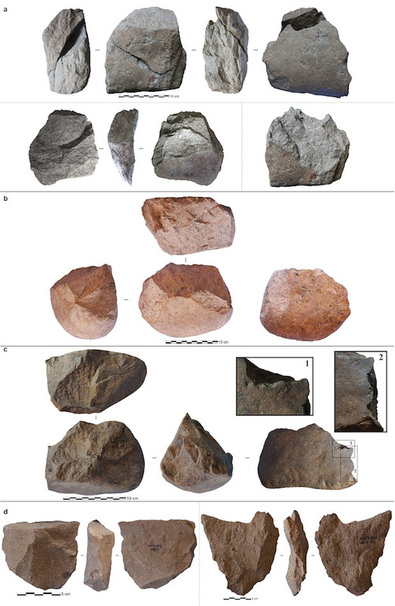

Photographs of some of the artifacts from LOM3 (Harmand et al. 2015:Figure 4).

Photographs of some of the artifacts from LOM3 (Harmand et al. 2015:Figure 4).

Spoiler alert: The stone tools from Lomekwi 3 are an important finding, but not a surprising one.

Hyping and over-simplification by the popular media of scientific findings are a fact of life, and I understand the need to find an "angle" for a summary story. I find the media's coverage of the Lomekwi paper particularly annoying, however, because of the general implication that the discovery of tools of that age somehow caught us all by surprise. It didn't. Anyone who has been paying attention to the field for the last few decades will not be surprised at all by the claims that: (1) there are stone tools that pre-date Oldowan; (2) those tools were probably not made by members of the genus Homo; and (3) the use of stone tools can be traced back to at least 3.3 MYA.

Let me be clear: this is a very important finding, just not a particularly surprising one. The tool assemblage from Lomekwi 3 (LOM3) fits very comfortably within an emerging picture of tool use pre-dating Oldowan and Homo. That picture has been coming into focus for decades now, thanks to a lot of hard work by many different scientists. The LOM3 tools make a significant contribution to that picture by providing a line of direct evidence that was previously absent. For the first time, we get some idea of what pre-Oldowan stone technologies might have been like. I think it was only a matter of time, however, and there will be a lot more coming down the road.

Why did we expect stone tools pre-dating Oldowan to be found?

First, as pointed out in the LOM3 paper, the 3.3-million-year-old age of the tools is consistent with the 3.4 MYA cutmarked bones from Dikika, Ethiopia that were reported several years ago. Not everyone accepts those cutmarks as legitimate (here is a John Hawks' post about the critique), however. I'm not a cutmark expert, so I don't really have a strong opinion. I'll just say that finding a stone tool assemblage in east Africa that dates to the same time period as the purported cutmarks mitigates the "but where are the tools?" question for me.

Second, the idea that only humans use tools (and therefore evidence of tool use should only be associated with the genus Homo) is an antiquated one that has been solidly falsified by studying living, non-human primates. The use of tools has been widely observed among wild chimpanzees, our closest living relative (and also among more distant relatives such as orangutans and gorillas). The most parsimonious explanation for the presence of tool-using behaviors in chimpanzees and humans is that those behaviors were also present in the Last Common Ancestor (LCA). If correct, that means that all hominids/hominins (as well as all members of the lineage leading to chimpanzees) had some capacity to make and use tools. If not correct, we need to explain the independent emergence of tool use in both lineages. I think the first possibility (that the capacity to use tools is a homology) is more likely, and makes it much easier to explain the widespread use of tools among great apes and some other primates. The LOM3 assemblage pushes our understanding of a particular kind of tool use (stone tool use) back in time, but it is by no means at odds with the general idea that all hominids had the capacity to use tools. It provides direct evidence, rather, to help evaluate hypotheses about the timing and nature of the evolution of tool-using behaviors that are peculiar to humans.

The presence of tool-using behaviors among several of our closest relatives suggests that the cognitive hardware required for tool use was present deep in the Great Ape lineage: it doesn't take a big, human-like brain to make and use simple tools. But what about other parts of our anatomy?

|

Human hands and chimpanzee hands -- both of which are capable of making and using tools -- differ significantly in several ways. Walking on two legs has removed selection related to locomotion from affecting the human hand, allowing our hands to be more-or-less optimized for manipulating objects (e.g., making and using tools). As quadrupeds, chimpanzees operate under a different set of restraints. A chimpanzee's hand anatomy reflects compromises between an appendage that can be used to manipulate objects and one that has to function for both arboreal and terrestrial locomotion. Those demands of locomotion have produced a hand with long fingers and a stiff wrist: long fingers are useful for grasping branches while a chimpanzee is in the trees; a stiff wrist serves to accommodate the forces that are transferred through a chimp's hand while it is walking on its knuckles.

The features of a chimp's hand make it harder for a chimpanzee to exert precise control over objects. The long fingers make a human-like "precision grip" (where the pad of the thumb is opposed directly against the pad of the index finger, as when you hold a key) impossible. The stiff wrist places limitations on the range of mobility. Although chimps can be taught to make and use simple stone tools (e.g., Kanzi), their hand anatomy works against them. |

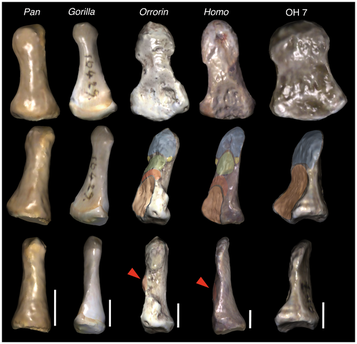

". . . the hand bones resemble those of Homo sapiens sapiens in the presence of broad, stout, terminal phalanges on fingers and thumb . . ." (Leakey et al. 1964:8).

As more fossil hands have been discovered in the decades that followed, it has become apparent that many hominids had "broad, stout, terminal phalanges" in their thumbs. The illustration above (from Almécija et al. 2010) shows the OH 7 thumb bone compared to the thumb of Orrorin tugenensis (a possible hominid from around 6 MYA), a modern human, a chimpanzee, and a gorilla. Orrorin had a broad thumb. What about robust australopithecines? Yep. Australopithecus sediba? Yep. It looks like there were a lot of hominids that may have had good features for tool-using hands. If Ardipithecus ramidus (4.4 MYA) was a hominid, it suggests that a chimpanzee's hand is in fact more derived from the ancestral condition than a human hand: the LCA's hand may have been "pre-adapted" for tool use with a pliable, mobile wrist. All that was needed to make the transition to a human-like hand was to shorten the long fingers (which could have happened in the process of shifting to a fully terrestrial adaptation) and broaden the thumb as a precision grip became possible. If tool use was at all important to our pre-Homo ancestors, the selective pressure to shorten the fingers would have been present all along, just less constrained once long fingers were no longer needed for a partially arboreal adaptation.

So it looks like the cognitive capacity for tool use among our ancestors was probably present by at least the end of the Miocene (in the LCA), and the changes to hand anatomy that allowed human-like grasping were well underway during the Pliocene (ca. 5.3-2.6 MYA). The discovery of stone tools dating to 3.3 MYA doesn't conflict with any lines of evidence that I know of suggesting when we could see the earliest stone tools. The interesting questions that we can start address with the publication of the information from Lomekwi, really, are the "who" and the "why" questions: Why did hominids start making and using stone tools? Which hominids were making these tools? And what did tool use have to do with other aspects of human and hominid evolution?

Harmand et al. (2015:314) find differences between the lithic materials from LOM3 and Oldowan, and propose that the technology be given a new name: Lomekwian.

"The LOM3 knapper's understanding of stone fracture mechanics and grammars of action is clearly less developed than that reflected in early Oldowan assemblages and neither were they predominantly using free-hand techniques. The LOM3 assemblage could represent a technological stage between a hypothetical pounding-oriented stone tool use by an earlier hominin and the flaking-oriented knapping behavior of later, Oldowan toolmakers."

The identification of "Lomekwian" tools is going to open up some new thinking about the roles of tool use in general (and stone tools in particular) in human and hominid evolution, not because stone tools at 3.3 MYA were unexpected, but because now we have some hard evidence of what those technologies might have been like. I don't work in Africa, but I'm probably not going too far out on a limb to suggest that there are plenty of places with mid- to late-Pliocene deposits that might be fertile ground for finding more direct evidence of these pre-Oldowan stone tool technologies. It's going to be great to watch that story emerge.

RSS Feed

RSS Feed