I'm coming up on the end of my second year in South Carolina. I think it takes a few annual cycles before you start to "get" the rhythms and tempos of seasonality in a new environment. Prior to coming here I had lived in the Midwest for most of my life, so there's a lot to learn.

As an archaeologist, I don't try to understand the environment just so I can give it a round of applause (if I had to pick what to applaud here, however, it probably would be the birds, flowers, and insects). Human societies and natural environments are inter-linked in numerous and complex ways -- figuring out those linkages and understanding how the "social" and "natural" parts of those coupled systems affect one another is an intrinsically interesting and profoundly important part of understanding how human societies work and how they changed in the past.

My point in writing this isn't to compose a fully-formed, well-researched argument, but rather to jot down a few observations/ideas/questions that have struck me since I transplanted myself into a region of the country with environments that are, in many ways, dissimilar from those of the Midcontinental interior with which I am most familiar (i.e., the Ohio Valley, the Till Plains, the Great Lakes). I don't have time to pull all these strings yet -- I'm just noting them.

First, the Deer . . .

Early on, I commented on what must be differences in the demography and behavior of a key Holocene large game species (white-tailed deer) across the different regions of the Eastern Woodlands. One would expect that those regional differences -- whatever they are -- would have articulated somehow with the behaviors of the human populations that exploited them. Generally, we presume that periodic (i.e., seasonal) aggregations of hunter-gatherer populations are useful to those societies for a number of demographic and social reasons. Logically, aggregations of large numbers of people have to take place when and where the resource base can support them. I would guess that most archaeologists in the north have a "fall aggregation" model in their heads, based in part on when deer are the fattest and least cautious. Are those conditions different in the Southeast, where the seasonal gradient is much less severe than in the north? Do deer populations go through boom/bust cycles? If so, are those linked to periodicities in mast production? Do those periodicities differ from region to region in the Eastern Woodlands? Deer hunting isn't everything, but it's surely something.

Second, the Sea . . .

At some recent conference, I had a conversation with a colleague who has been working in this region for a long time. It was clear he had had a few drinks, so he was probably telling me the truth. He said that the rhythms and tempos of hunting and gathering on the coast are very different than in the interior. I've never done coastal archaeology -- when I go to the beach it's usually to let the kids play, watch birds, and look for shells.

We were at Edisto last year during the time when the loggerhead sea turtles come ashore to lay their eggs. These are big animals, with adults weighing about 300 pounds (up to about 1000 pounds). The females come ashore at night during the summer to lay about 120 eggs in a nest in the sand.

Watching the Edisto turtle patrol identify and check nests every morning, I became curious about how turtle nesting behavior articulated with prehistoric coastal hunter-gatherers in this region. The nests are easily spotted by the tread-like path that turtles leave as they move across the sand. Caught in the act, the adult turtles are large packages of meat, sitting in the open, defenseless. Presumably a couple of people could flip one on its back and return later for an on-the-spot feast or to butcher the animal.

How much archaeological evidence is there of sea turtle exploitation on the Carolina coast? Does it change through time? Where would sea turtles rank in terms of a seasonally-predictable resource that could be used to support periodic aggregations? Were sea turtles part of coastal Carolina hunter-gatherer cosmology (perhaps in connection with the summer solstice)? I don't know the answers to any of these questions.

The birds here are beautiful, plentiful, varied, and constant. Of the 914 species of birds documented in the United States, over 400 occur in South Carolina. That's a lot of birds. Some sing all year round. Some even sing at night. It's fabulous.

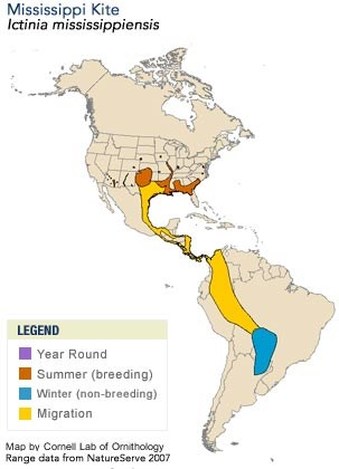

Migration and range of the Mississippi Kite (map from www.allaboutbirds.org).

Migration and range of the Mississippi Kite (map from www.allaboutbirds.org). These birds eat mostly flying insects, and you can see them circling over my neighborhood during much of the summer. Their appearance in the region seems to coincide with what I interpret as the "high" insect season -- the cicadas are hatching in force and there are things buzzing around everywhere. They're a signal of a season change here, perhaps much in the same way as the yearly arrival of Turkey Vultures north of the Ohio River.

However the annual long-distance migration/breeding pattern of the kites evolved, I would guess that the dense insect populations of the Southeast are a key to making it viable. That got me thinking about the effects of longer-term periodicities, particularly the those of the 13-year and 17-year periodical cicadas. The emergence of buhzillions of cicadas at the same time would surely make for easy living for the kites, as well as for game animals with an insect-based diet (e.g., turkeys). The periodical cicadas tend to damage trees, however, which reduces mast production (and hence could have a suppressing effect on deer populations). Did any of this factor into the characteristics (social, behavioral, cosmological, etc.) of the prehistoric human societies of this region? I don't know.

The completion of my second year in Columbia will be marked by a total solar eclipse that I'll be able to experience from my backyard on August 21 at 2:41 p.m. I've never seen a total eclipse before, and I may never see one again. Most people don't see one in their lifetime. I'm really looking forward to it. Thankfully I won't have to stay up late at night to see it.

Obviously, it's now old hat for us to predict these "anomalous" astronomical alignments with a great deal of accuracy (business depends on it). Given how infrequently these things occur and the low probability of any one person accidentally being in the right place at the right time to witness it, it's natural to wonder what prehistoric peoples would have made of this sort of phenomenon. I'm really curious as to what it will feel like to experience it firsthand (I'd also like to know what's it like to be in a hurricane, to break the sound barrier, to be close to a tornado, to fly at the edge of the atmosphere, to experience zero gravity, etc., in case your looking for ideas for my birthday).

So What?

Somewhere in all this mess, there's a question to be crystalized about how human societies "tune" themselves to the predictable and unpredictable fluctuations in their environments. What are the feedbacks? What are the dampers? What are the common denominators? What is the range of risk/variability that societies create cultural rules or behaviors to respond to? What happens when the needle moves outside of that range? Which parts are robust? Which parts break? How do responses scale to the size and predictability of perturbations across time and space? I have no answers right now, just questions.

And now I've got to move on and do other things.

RSS Feed

RSS Feed