Understanding when, how, and why this distinctly human reproductive strategy developed is a great evolutionary question. Reducing the IBI increases the potential fertility of human populations, but also creates new demands on the energies of parents and families. Human families today often offset those extra energy demands by getting help (evolutionary anthropologists call it “cooperative breeding”). A new paper in the Journal of Human Evolution titled “When Mothers Need Others” by Karen Kramer and Erik Otárola-Castillo tries to further our understanding of where cooperative breeding comes from, using an “exploratory model” to try to understand the selective pressures associated with the evolution of human-like patterns of reproduction and child-rearing. The goal of the paper “is to develop a model to predict those life history transitions where selective pressure would have been strongest for cooperative childrearing” (pg. 5).

Kramer and Otárola-Castillo call their model the “Force of Dependence Model.” Their model is a simple one, calculating “the net cost of offspring as a function of dispersal age, birth intervals and juvenile dependence” as a 3-dimensional surface (Supplementary Online Material from Kramer and Otárola-Castillo 2015). The authors use several different combinations of settings to represent a range of conditions from “ancestral” (juvenile independence at age 10, IBI of 6 years, and a dispersal age of 14) to “most derived” (juvenile independence at age 20, IBI of 3 years, and a dispersal age of 20). Their graphs show that “net costs” within a domestic group (a mother and her offspring) are lower when offspring are spaced further apart and become independent at a younger age. When offspring hang around past the age of juvenile independence, there is a net benefit to the domestic group as their productive capacities can be used to offset the drain of their younger siblings. The authors find that the strain points – where selective pressures for assistance would be greatest – occur in domestic groups with the most derived set of characteristics: late juvenile independence and a low IBI (lots of children who remain dependent for a long time).

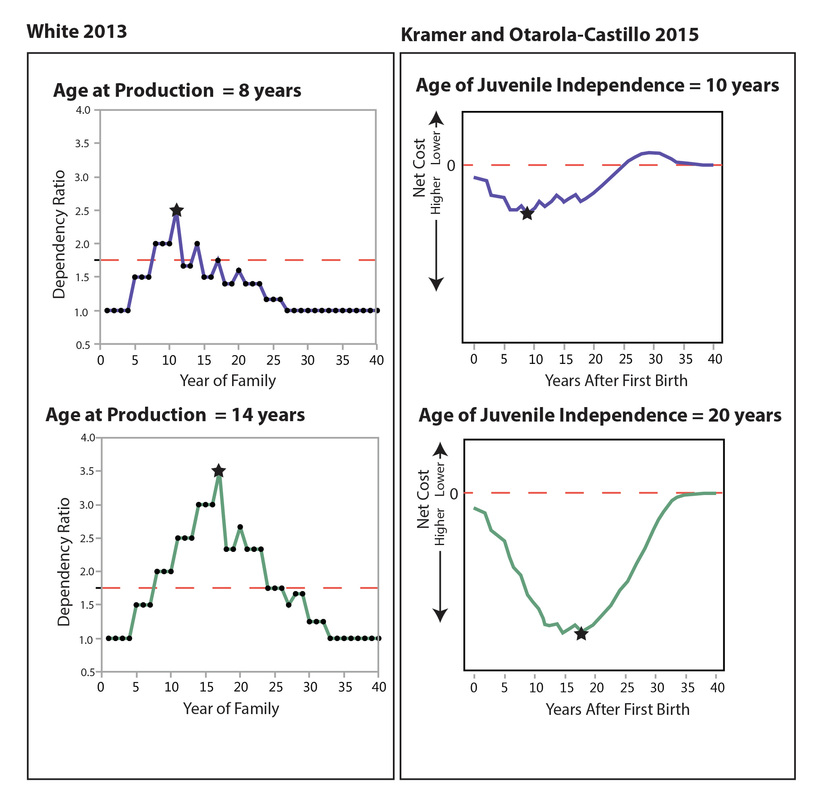

As I understand it, the “net cost” in this model more-or-less mirrors the dependency ratio (the ratio of consumers to producers) of a domestic group or family, something anthropologists have been interested in understanding for a long time. The higher the ratio of consumers to producers, the higher the dependency ratio, and the higher the “cost” to each producer supporting the family. The dependency ratio changes through the lifespan of a family in a patterned way: every domestic group that has children goes through a “pinch” period when the dependency ratio is highest, and the pinch period logically corresponds to the time when there are a lot of dependent offspring. As I wrote in my 2013 paper in the Journal of Anthropological Archaeology (“Subsistence Economics, Family Size, and the Emergence of Social Complexity in Hunter-Gatherer Systems in Eastern North America,” available here):

“the duration and amplitude of the ‘pinch’ is affected by the rapidity of the addition of offspring and how quickly those offspring turn from consumers into producers. The rapidity of addition of offspring will depend on factors such as fertility, infant and childhood mortality, and the number of wives. The productive potential of children will be affected by the presence and distribution of resources that can be procured by children and the foraging strategies that are employed to exploit those resources” (White 2013:128).

The main part of that paper used an agent-based model (ABM) to try to understand how the distribution of family size changes when the age at which children become producers (the “age of juvenile independence” in Kramer and Otárola-Castillo’s model) decreases and there is an incentive for polygynous marriage. In addition to the ABM, I used a simple spreadsheet model to show how the dependency ratio changed through the course of the developmental cycle of an individual family in cases where the age at production was low (8 years old) and where it was high (14 years old). In this simple model, I used an IBI of 3, a dispersal age of 16 for females and 20 for males, and a female reproductive period spanning ages 20-35 years (giving a total fertility of 6 offspring).

The figure below compares Kramer and Otárola-Castillo’s graphs from their cases with early and late juvenile independence (holding IBI at 3 and dispersal age at 14) with my data on changes in dependency ratio through the developmental cycle in cases with a single reproducing female and an age at production of 8 (top) and 14 (bottom). My model data are the same as in my 2013 paper (Figure 5), but I have re-graphed them to make comparison with Kramer and Otárola-Castillo’s figure easier. I have redrawn the graphs from Kramer and Otárola’s Figure 1 (third graphs from the left, top and bottom rows). The dotted lines on the graphs of my results indicate a dependency ratio of 1.75, which is what I have generally used in my modeling efforts as a “typical” dependency ratio among hunter-gatherers (following Binford 2001:230).

The correspondence between my results and Kramer and Otárola-Castillo’s is unsurprising. The idea that the dependency ratio of a domestic group changes through the course of its developmental cycle in a somewhat predictable way is not new (and the idea that the “pinch” comes when you have lots of little kids running around at the same time won’t come as a revelation to anyone who has multiple children). This is a phenomenon that has been studied for decades (e.g., Chayanov 1966; Donham 1999; Fortes 1958; Goody 1958) and recognized as a key aspect of how hunter-gatherers organize themselves (Binford 2001:229).

So where does this kind of work put us in terms of understanding the evolution of human reproduction, society, and family life? I think it primarily puts us in a spot where we’re asking some good questions. Going back to the issue of the origins of monogamous pair-bonding (which I touched on briefly in this post about birth assistance and this post about australopithecine sexual dimorphism), having a two person (male-female) unit forming the core of a domestic group would have a mitigating effect on the strain caused by a decrease in IBI (i.e., you’d be adding another producer into the equation). If the appearance of male-female pair-bonding was associated with a sexual division of labor (which is I think what most of us would hypothesize), males and females would presumably be focused on procuring somewhat different sets of subsistence resources. Offspring could be largely “independent” with regards to some of those resources but not to others – think about the difference between collecting berries and running down large game. A sexual division of labor and an environment where relatively young children could make some contribution to their own subsistence (even if that contribution does not include the full range of resources that are exploited) would go a long way toward easing the “pinch” that comes from having more children spaced closer together.

When does this happen in human evolution? Of course that’s a tough thing to get at directly. I think if you took a poll, the winner would probably be “around the time our genus emerges” or “with Homo erectus.” An increase in total fertility (coincident with a lowering of the IBI) would help explain the population growth that must have been part of the dispersal of our species out of Africa prior to 1.8 million years ago. It would also fit nicely with the evidence for an increased exploitation of animal resources around that same time. Maybe Glynn Isaac was right all along to propose the emergence of human-like central place foraging with home bases and a sexual division of labor at the beginning of the Lower Paleolithic?

But what if monogamous pair-bonding and a sexual division of labor appeared much earlier – with australopithecines or even some pre-australopithecine like Ardipithecus? If those things came along with bipedal locomotion, would a decreased IBI and increased fertility have followed automatically? Maybe not. Perhaps those earlier hominids just didn’t have the wherewithal to exploit their environments like later hominids did – perhaps the diversity of the resource base they could exploit wasn’t great enough to really leverage a sexual division of labor until animal products became readily attainable. That may have required a suite of anatomical adaptations for daytime exhaustion hunting (loss of body hair, skin pigmentation, greater body size, stiffer foot) and cognitive/behavioral adaptations for making and using stone tools to process carcasses. The date of the “earliest” proposed use of stone tools continues to be pushed back (now it’s at 3.3. million years ago), but as far as I know the density of stone tools and butchered animal bones that appears at about 1.8 million years ago is unlike anything that precedes it.

More modeling work will be required to really understand how changes in the dependency ratio might have articulated with changes in reproductive, social, and technological behaviors deep in human prehistory. In order to understand what changes in reproduction might have meant in terms of social interactions, however, we’ll need a different grade of model than that used by Kramer and Otárola-Castillo. Of course I’m going to say that complex systems modeling is the way to go on this: it will let us get past the limitations of deterministic inputs and help us understand how constraints, costs, and interactions would have played out within a society. In order for “others” to help with raising and provisioning multiple dependents, those others had to have existed within these small-scale hominid societies and (again, speaking as someone involved in raising multiple small kids) there wouldn't have been some inexhaustible Plio-Pleistocene babysitting pool of “others” out there just waiting to step in and provide extra calories for a few years. A different kind of modeling effort with broader scope will let us get at the group- and society-level contexts in which family-level changes in child-bearing and child-rearing would have played out. Stay tuned.

Binford, Lewis R. 2001. Constructing Frames of Reference: An Analytical Method for Archaeological Theory Building Using Hunter-Gatherer and Environmental Data Sets. University of California Press, Berkeley.

Chayanov, A. V. 1966. A. V. Chayanov on the Theory of Peasant Economy. University of Wisconsin Press, Madison.

Donham, Donald L. 1999. History, power, ideology: Central issues in Marxism and anthropology. University of California Press, Berkeley.

Fortes, Meyer. 1958. Introduction. In The Developmental Cycle in Domestic Groups, edited by Jack Goody, pp. 1-14. Cambridge Papers in Social Anthropology. Cambridge University Press, London.

Goody, Jack. 1958. The Fission of Domestic Groups among the LoDagaba. In The Developmental Cycle in Domestic Groups, edited by Jack Goody, pp. 53-91. Cambridge Papers in Social Anthropology. Cambridge University Press, London.

RSS Feed

RSS Feed