This year's Southeastern Archaeological Conference (SEAC) is in Athens, Georgia, which I hear is very nice. I put together a small symposium titled "Hunter-Gatherer Societies of the Late Pleistocene and Early Holocene Southeast" (session 35 in the program). I originally wrote about the idea last April. We ended up with papers by seven presenters: Al Goodyear, Doug Sain, David Thulman and Maile Neel, Kara Bridgman Sweeney, Joe Wilkinson, Sarah Gilleland, and me. Here is the symposium abstract:

"Societies are groups of people defined by persistent social interaction. While the characteristics of the late Pleistocene and early Holocene hunter-gatherer societies of the Southeast certainly varied, archaeological data generally suggest that these societies were often geographically extensive and structurally complex. Patterns of artifact variability and transport, for example, demonstrate that small-scale elements (e.g., individuals, families, and foraging groups) were situated within much larger social fabrics. This session aims to explore the size, structure, and characteristics of early Southeastern hunter-gatherer societies, asking how patterns of face-to-face interactions at human scales “map up” to and are affected by larger social spheres."

I decided to use my contribution to think about the issue of a possible abandonment of the deep south during the later portion of the Early Archaic period. Here is the abstract for my presentation, titled "Social Implications of Large-Scale Demographic Change during the Early Archaic Period in the Southeast:"

"Previous studies of radiocarbon and projectile point distribution data have suggested the possibility of a significant shift in the distribution and/or behaviors of human populations during the later portion of the Early Archaic period (i.e., post-9000 RCYBP). This paper considers the evidence for an “abandonment” of large portions of the Southeast following the Kirk Corner Notched Horizon and explores (1) possible explanations for large-scale changes in the distribution of population in the Early Holocene and (2) how those demographic changes, if they occurred, might have articulated with social changes at the level of the family, foraging group, and larger societies."

I first became interested in the Early Archaic abandonment issue while reading Ken Sassaman's (2010) book Eastern Archaic, Historicized. Working on this presentation was fun because it forced me to try to think through some of the issues about how we would recognize a large-scale abandonment, what the abandonment process actually would have been like, and what the social ramifications might have been for the people and societies involved in that process. I'll tweak the presentation before I give it, but it's pretty close to done.

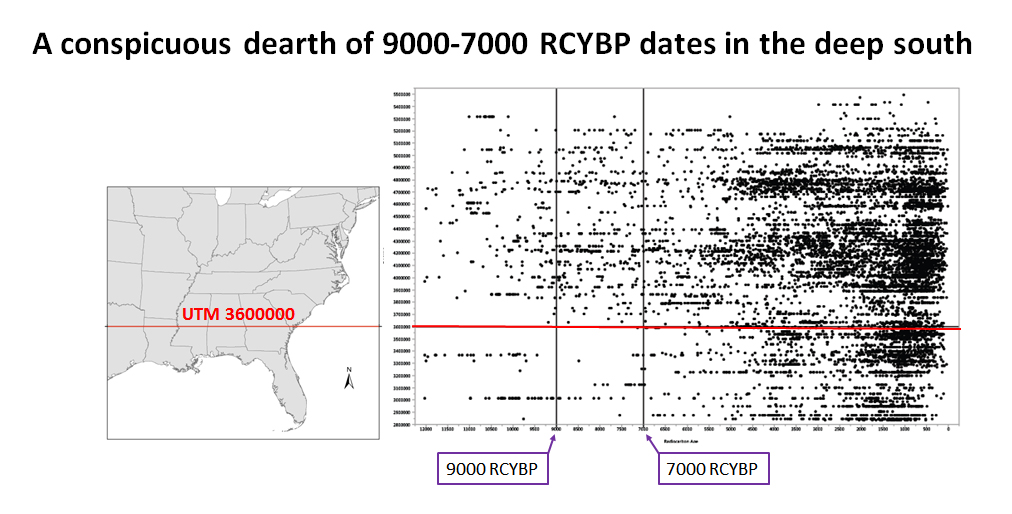

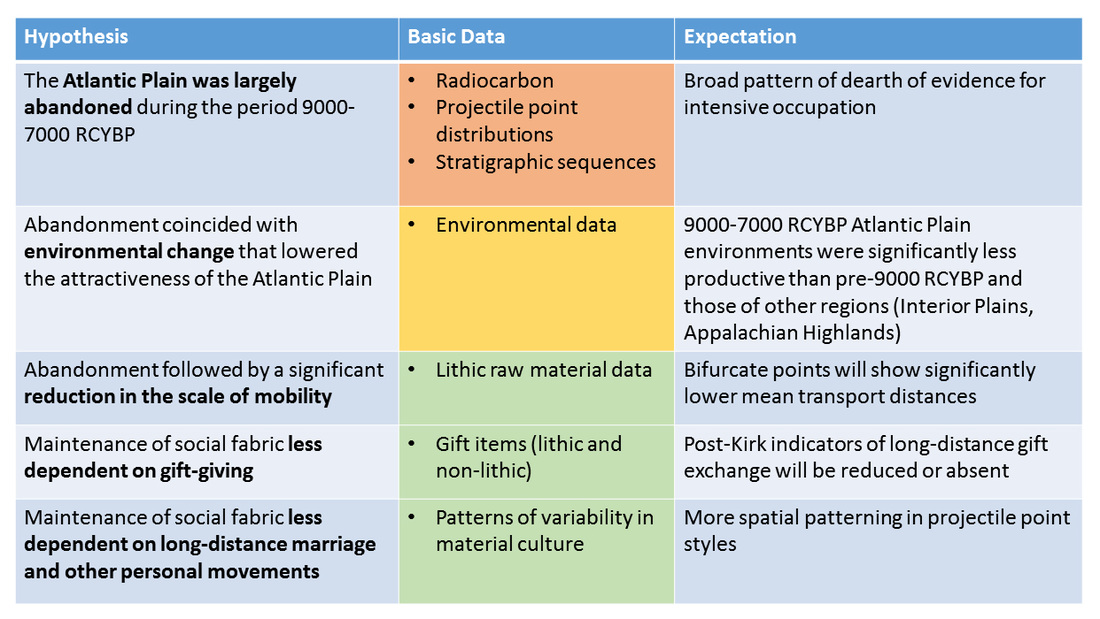

The first question is to ask is whether or not there was a large-scale abandonment of parts of the Southeast. On the surface (at least), I think the case is fairly compelling. Following the example of Faught and Waggoner's (2012) paper about Florida, I started compiling radiocarbon data from across the Eastern Woodlands to evaluate the idea. At 9,500 dates and counting, the radiocarbon database that I'm working on clearly supports the idea that there are far fewer than expected dates from 9000-7000 radiocarbon years before present (RCYBP) in the deep south:

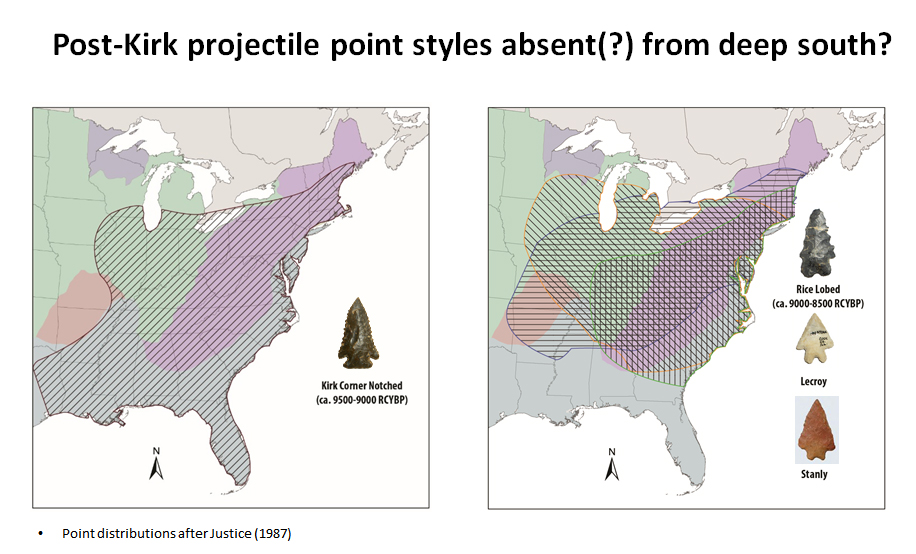

The idea of a large-scale abandonment is also consistent with the distribution of post-Kirk lobed/bifurcate projectile points, which (unlike Kirk), does not extend into Louisiana, Florida, and southern Mississippi, Alabama, and Georgia.

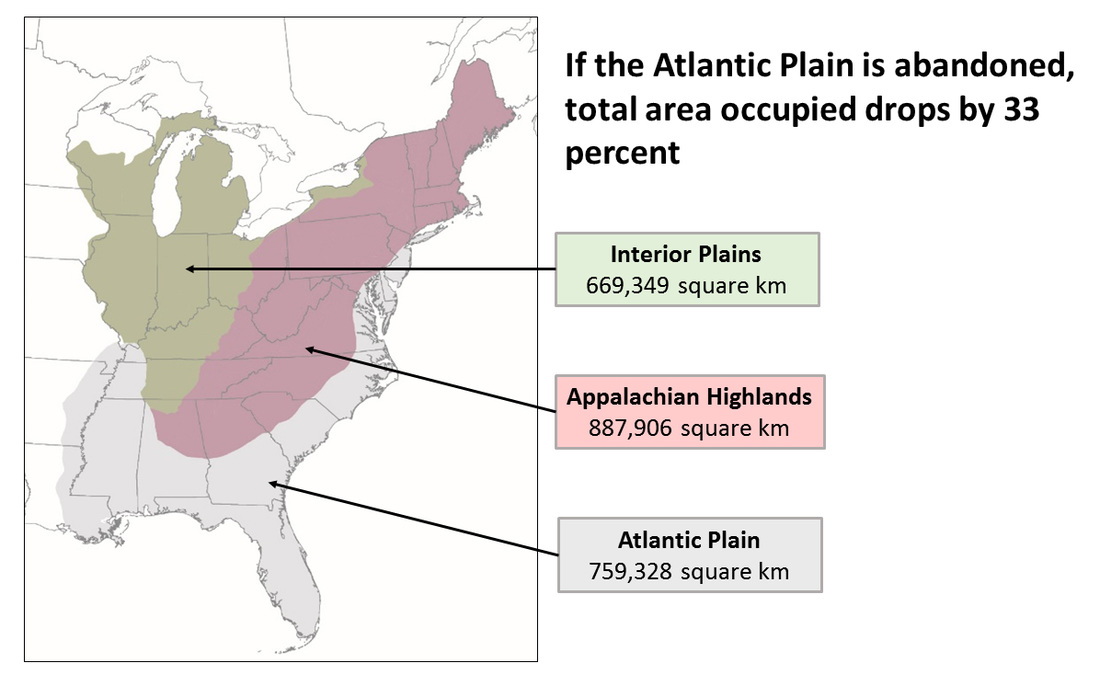

But how would an abandonment actually take place? I can think of several ways that populations could shift out of an area. My gut is that an abandonment of the Atlantic Plain during the late Early Archaic would have most probably involved a contraction of populations into the Appalachian Highlands and Interior Plains. One of my favorite of Lew Binford's papers is his (1983) discussion of how hunter-gatherers often make extensive use of the landscape. Keeping his examples in mind, it's easy to imagine how "abandonment" could actually be the end result of a long-term process involving segments of the population getting "pulled in" to better quality environments in the course of normal decisions about movement.

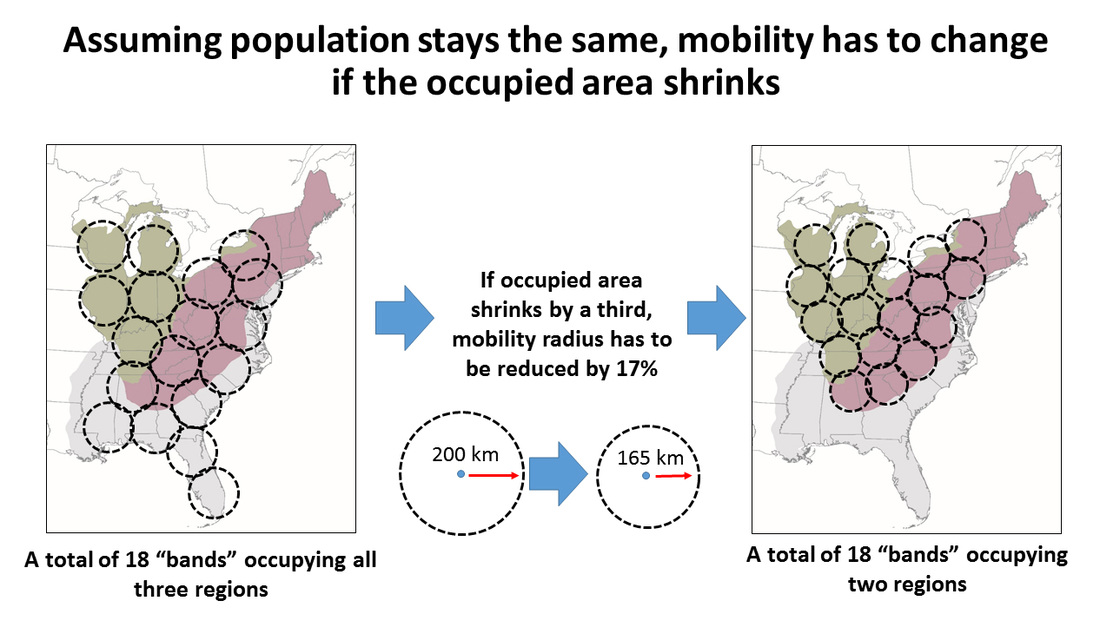

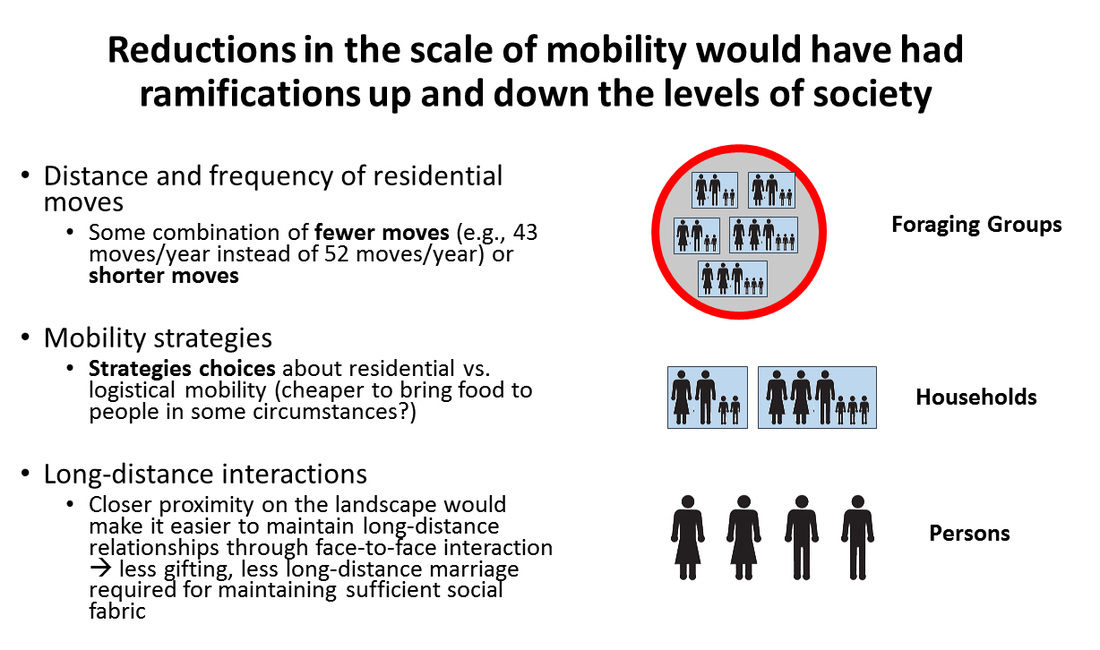

Assuming population size stayed constant, this shift would have necessarily involved changes in mobility. If (based on Midwestern data) we assume that Kirk "bands" had a group mobility radius of about 200 km, there would have been room for about 18 such "bands" in the Eastern Woodlands. If you took that same population and crammed them into an area 33% smaller (i.e., the Eastern Woodlands minus the Atlantic Plain), the scale of group mobility would have to be reduced by 17% (mobility radius of 165 km) to keep everything else the same.

For me, this presentation was a machine for thinking. I can't "prove" anything, but going through the process of committing to an idea and preparing a presentation has forced me to attempt to think through some complex, interesting issues. I'm hoping I'll get some good feedback on my ideas ("interesting" and/or "you're full of it"), which obviously involve an extensive geographic area that I make no claim to have mastered.

I also hope to take full advantage of my hotel and at least quadruple my supply of ink pens. Every little bit helps.

RSS Feed

RSS Feed