Over the course of about a year of engaging with various elements of the "fringe" online, I've been impressed by how the purveyors of "fringe" ideas (who run the gamut from the honestly curious to the outright fraudulent) have adapted to the internet. My sense is that, overall, they have been doing a much better job than professional archaeologists and historians of understanding and using the capabilities of the web to rapidly communicate ideas. Yes, the celebrated American Antiquity pseudo-archaeology book review section from the past summer was a step in the right direction, but as far as influencing public opinion it was a spitwad aimed at a Sherman tank. We're spending too much energy repeatedly debunking the Top Ten Bogus Artifacts from the last century and far too little energy building the capacity to address new silliness in real time as it emerges.

I've gotten some criticism for how much I've focused on Swordgate (the recent claim that a "Roman sword" was found in the waters of Nova Scotia). While a few of my readers may be getting bored, I don't think that any of the time or energy I've spent on the issue has been wasted. Swordgate is important, I think, because it provides an ideal example of how these kinds of battles unfold and what we can actually do to contribute to the story as it develops. If our response is to wait a year (or five years, or ten years) to note that there are many reasons to doubt the claims about the "Roman sword," we lose. Sitting back and chuckling in disbelief as various news outlets report that "historians" have found a "Roman sword" that will "rewrite history" is not a helpful strategy of engagement.

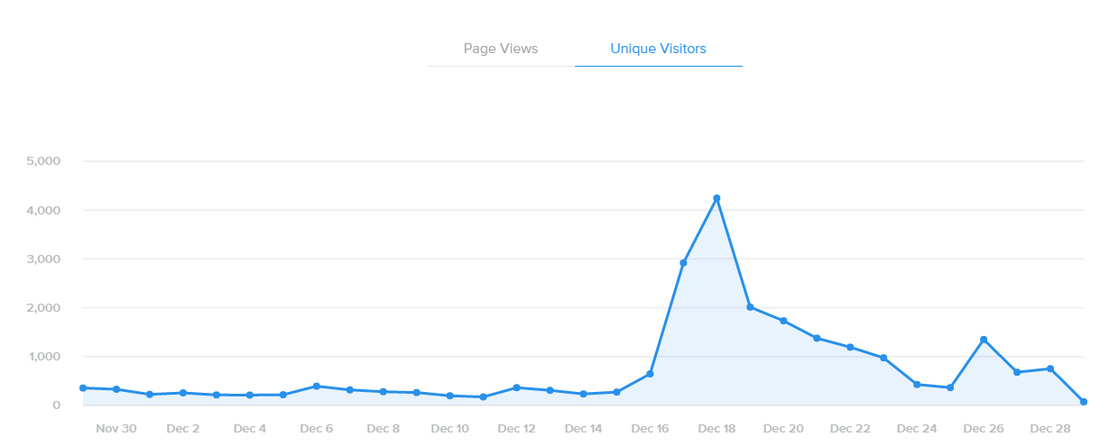

People interested in the sword story from the beginning (before it was republished by many other online media outlets) were able to find my original post easily: it provided a different perspective for those who were most interested in the story and, consequently, searching for additional information. As the comments started coming, it was evident that I wasn't the only one who thought something was fishy. One person commented on the post with a link to a site that showed images of a very similar sword in a Florida collection. That led to this post. Soon after, someone contacted me by email to tell me he also had a similar sword that he had purchased in California (in terms of the number of Facebook likes/shares, the California sword post is the most popular thing I have ever written). By that time, it was clear that a crowd-sourced effort at understanding the meaning of the alleged "Roman sword" was underway. The crowd rooted out another similar sword on Italian Ebay, and it was discovered that modern reproductions of this same Hercules-hilt sword design were available at Walmart and other home/garden stores (the Design Toscano swords).

It's also a phenomenon, I think, that casts the "journalism" I've seen on this topic in a pretty poor light. The stories that have been published about the "Roman sword" are mostly just edited from parts of previous stories. They make me wonder what it means to actually call yourself a journalist these days. Do the "journalists" at these media outlets feel no compulsion or responsibility to ask any critical questions before reprinting this stuff (and slapping their names on it)? I went to journalism school, and I have a journalism degree. I understand what is supposed to be involved in getting a story right. That's not happening out there. Readers of this blog have dug up more interesting information relevant to Swordgate than all the "journalists" put together. While several stories (like this one in The Inquisitr and this one in The Examiner) have appended "updates" pointing to this blog, no journalist has ever contacted me for a different opinion prior to publishing his/her story. Overall, the journalism has been pretty lazy, if you ask me. It's not that I have all the answers, but I can surely help a journalist understand some questions they should consider before endorsing this "re-writing of history" that they've been spoonfed.

It matters to me when people tell lies about the past. I don't like it, and I think it's problematic for several reasons other than the simple fact that what's wrong is wrong. If you don't agree, you probably stopped reading this a long time ago. If you agree with me, however, there are several things you can do to help the situation we now find ourselves in (losing the information war). First, try to understand the information landscape: join Facebook groups that take you outside your peers and into the worlds where claims about the past matter for all kinds of non-academic reasons. Second, engage: identify nonsense when you see it, and prepare to back up your argument. Third, create resources: create a presence on the web that will be there for people seeking information. Fourth, keep your finger on the pulse: be prepared to identify and evaluate new claims as they emerge.

This post turned out to be nothing like what I sat down to write. That happens sometimes. Happy New Year!

RSS Feed

RSS Feed