Last Night's Episode of The Curse of Oak Island

We finally got to see the sword on television. As I mentioned yesterday, I haven't watched The Curse of Oak Island at all this season. The first part of the show reminded me why I tuned out midway through season 2: the pacing is so slow it's painful. I've spent much of my career as a professional archaeologist digging in the ground, supervising other people digging in the ground, and talking to people about digging in the ground. Archaeological excavation done in real time, as painstaking a process as it can be, moves along at a faster clip than this program. And there are fewer commercials. It's just flat out boring.

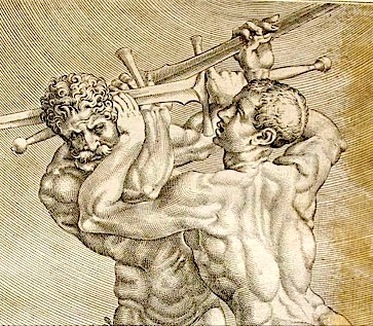

Anyway, they finally unsheathed the sword from its protective towel in the last few minutes of the program. Following the oohs and aahs, Charles Barkhouse proclaims it to be "Roman sword" and regurgitates the main points about gladiators, Hercules, and Commodus that can be found on the website of the owner of the Florida sword. So there's nothing new there, except it might provide further evidence as to the origin of the interpretive narrative that seems to be attached to the sword among its proponents. If you haven't read this post about Hercules, Commodus, and the Florida sword, I encourage you to do so. It is worth noting that Dr. Steven Tuck, who included the Florida sword in the Experiencing Rome lecture series, does not consider his discussion of that sword to constitute an endorsement of its authenticity as a Roman artifact. Further, he told me that he thinks the Nova Scotia sword is probably "a tourist piece made to sell to tourists from the past few centuries."

One thing we did learn from the program (and the live show Drilling Down that followed) is that we'll see the sword again next week. It's going to be examined by Dr. Myles McCallum at Saint Mary's University. I don't know Dr. McCallum. I look forward to seeing what he has to say about the sword.

It also appears that we will possibly get some metallurgical analysis on next week's show. There was a shot of someone in a lab coat holding the sword, and I think she said something about the metal (I don't have a DVR, so I'm just going by memory -- correct me if I'm wrong).

We also learned that the blade of the sword apparently is formed by two pieces joined together, suggesting maybe it was broken and then repaired. That made sense to me, as I thought I detected a color/texture difference in that part of the blade in some earlier photos that I saw. I'm not sure exactly what the significance of a repair would be, but I will note that the blade of the California sword (which I now have in my office) also appears to me as if it might be two separate pieces joined together.

Finally, I think the language (both body and verbal) of the cast during Drilling Down is giving us a clue as to the content of next week's show. I think at least twice someone said something like "We just don't know if it's 2000 years old or 200 years old." The way they were passing the sword back and forth and waving it around seemed much more consistent to me with how one would treat a 200-year-old souvenir sword rather than a priceless, gold-gilded, "smoking gun" artifact that would forever changed history as we know it. I'm not a great poker player, but I read "bluff" on that one. We'll see if I'm right.

I have noted previously that the media "reporting" on this story has really been poor. Much of the coverage has been cut-and-paste stories that ask few questions and provide little if any reason for actually writing a new story.

So I'd like to call your attention to a story titled "Oak Island's Roman Sword Saga Unsheathed" in this morning's Halifax Chronicle Herald. I talked to a reporter briefly for the story last week, and I'm quoted in it a few times. It's not what I have to say that makes the story notable (I'm mostly quoted as saying fairly ineloquent things, but that's why I prefer writing to speaking off the cuff), but that the reporter(s) took the time to ask some questions, sniff around, and try to understand the context of the story and add something to the narrative. Holy cow - we've got journalism! Thank you, Chronicle Herald!

Here's a taste (but you should really read the whole thing):

"“You have to decide whether you may or may not want to participate in a hatchet job?” Pulitzer said Friday when asked critical questions about his research.

When questioned, Pulitzer would not say whether he has a degree in history.

“Is it enough that I have written 300 history books,” responded Pulitzer.

“Is it enough that I’ve published over seven million words on ancient and lost history? Is that enough?

“Is it enough that I am a professional researcher with a specialty in forensic investigation? That I have patents in 189 countries. Is it enough that 11.9 billion cellphone devices use my patents?"

None of Pulitzer's claims have been verified by The Chronicle Herald."

For some reason he left out "Smithsonian laureate." It will be interesting to see the reaction to the article.

Finally, it's increasingly unclear to me whether the "forbidden truth" fans out there really want the attention of academics or not. They love to play the "nobody is paying attention to our important ideas" card when it suits them, but are very quick to switch to the "being attacked by the establishment" card when their ideas come under actual scrutiny. Which is it? Should I stay or should I go?

My attention to the "Roman sword" has made that discomfort more visible to me than ever before. I've seen many misrepresentations and mischaracterizations of the questions I've asked, the arguments I've made, and the data that are available. It's discouraging, but not totally unexpected. I've seen people online say that I'm on a "paid campaign" to discredit the sword no matter what. I've even seen people say that I should be fired from my job for . . . what now? Being a scientist interested in a purportedly important claim about the past? That's actually part of my job.

Let me tell you something about how good science works. Scientists question things. Scientists are naturally skeptical. It is our job to ask questions like "is that a credible explanation?" and "can I prove that wrong?" Asking a skeptical question is part of the process. If you're not doing that, chances are you're not doing science.

The skeptical questions get asked in a lot of different ways as scientists do science and interact with one another. Sometimes it happens over lunch. Sometimes in the lab. Sometimes at a conference. Sometimes in print. It happens continually, all over the place. The "battlefield" of arguments, evidence, and ideas is everywhere.

Pulitzer chose the internet as the battlefield where he would make his case. He did that as a deliberate part of his strategy. As reported in the Chronicle Herald story,

"His strategy is to communicate directly with the public rather than through academic intermediaries he considers to be perpetrators of a myth about how Europeans settled the Americas."

I shouldn't have to say it, but I will: if you pick the internet as the battlefield, then that's where the battle is going to take place. It's simple. He picked it, not me. And I'm fighting fairly. I'm not fighting with an a priori assumption that the sword is a fraud/hoax/whatever. What I'm doing is fighting to have the conversation that we should be having about such a bold claim. Don't mistake asking a tough question about evidence for outright rejection of an idea - they're not the same thing at all.

Given where the battle is taking place, I'm doing the best I can to ask the questions that should be asked in a timely manner. They are the same questions that I would ask if I was handed a published paper (wouldn't that have been nice!). I have not misrepresented what Pulitzer has said (he has not returned the favor), but have tried to factually address both the evidence he has put forward as well as the glaring omissions in his case. I have not threatened legal action against him (as he has done to me) for making untrue statements about me. I don't intend to prevent him from making use of the images that I have produced as part of this story (as he has done to me). I'm not in the second grade anymore, and I don't intend to act like it. I wish that were true of everyone involved in this story.

Good science is based on skepticism and healthy flow of information. It seems to me that many fans of "forbidden history" would like to pretend that they're doing science but without all the hassle and discomfort of actually following the rules and practices that are fundamental to the scientific process. I'm sorry to tell you, but you don't have a very good chance of arriving at plausible explanations that way. If you guys are going to play in the big kid sandbox, you'll need to put your big kid pants on at some point and make an effort to understand how science works (hint: it's not via legal threats and misrepresentations).

You have to decide if you want academic attention or not. You can't have it both ways.

RSS Feed

RSS Feed