Those large teeth still fuel discussions of what the anatomy of Gigantopithecus was like. Estimates of very large body size (1000 lbs . . . 1200 lbs . . . ) attract a quantity of attention from Bigfoot enthusiasts, Creationists, and other "fringe" theorists that far exceeds that paid to other fossil apes. But where do those estimates come from? As I discussed briefly in this post, all of our information about Gigantopithecus is based on isolated teeth and a handful of mandibles. That's something to go on, but not a lot. The complicated nature of the relationships between body size and tooth size, problematic when the first teeth of Gigantopithecus were discovered in the 1930's, remains an analytical issue today.

How do we go from tooth size to body size? Very carefully. Stanley Garn and Arthur Lewis discussed the matter in a 1958 paper in American Anthropologist titled "Tooth-Size, Body-Size and 'Giant' Fossil Man:"

"On the basis of morphology and size together, Von Koenigswald decided that the Hong Kong and Sangiran teeth and jaw fragments came from “giant apes.” However, Weidenreich later concluded that both the 1935-1939 Hong Kong [Gigantopithecus] teeth and the 1939-1941 Sangiran [Meganthropus] tooth-jaw fossils were the remains of true men, though extraordinarily large men, from the early Sino-Malaysian fauna (Weidenreich 1945:123-24). Finally, in his recent article, W. C. Pei reverted to the idea of a giant anthropoid and estimated that the “giant” ape of Luntsai stood “some twelve feet” high (Pei 1957:836).

What is the evidence that these three sets of finds, separated from each other by space and time, all came from gigantic beings? How convincing is the evidence that big teeth necessarily indicate extraordinary stature? Lacking the postcranial skeletons, direct proof of body size does not exist. What remains is such indirect proof as can be gleaned from tooth-size relationships in man and apes. “This” admitted Franz Weidenreich . . . “is a very ticklish question. . . "

The question is "ticklish" because of the fact that tooth size, in addition to being related to body size, is also related to things like diet. Similar-sized animals that eat different things emphasize different teeth. Animals that have to grind a lot of tough plant food tend to have cheek teeth (molars and premolars) with large grinding surfaces. Animals whose diet consists of softer foods (like fruits) or involves lots of cutting and tearing (as in carnivores) typically don't have large chewing teeth relative to their body size because they don't need them (they're not selected for).

At the time Weidenreich wrote his 1945 monograph "Giant Early Man from Java and South China," the known fossil remains of Gigantopithecus consisted of just three teeth. Weidenreich's detailed comparative analysis of those teeth convinced him that Gigantopithecus was a hominid and a human ancestor. His discussion of the possible size of Gigantopithecus, while following from that conclusion, was cautious (pg. 111):

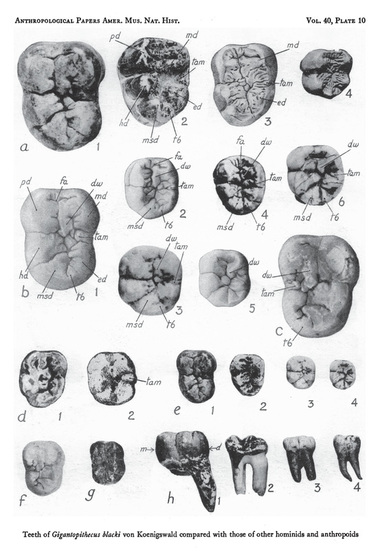

Plate 10 from Weidenreich (1945) showing the three original Gigantopithecus teeth (a, b, and c).

Plate 10 from Weidenreich (1945) showing the three original Gigantopithecus teeth (a, b, and c). Weidenreich died in 1948 and never got to see the Gigantopithecus mandibles that were discovered in the late 1950's. Consideration of those mandibles (and the growing number of isolated teeth available for study), led Elwyn Simons and Peter Ettel to argue in a 1970 article in Scientific American that Gigantopithecus was a large, herbivorous ape weighing as much as 600 lbs (272 kg) and standing about 9' (2.7 m) tall when upright. Simons and Ettel reconstructed Gigantopithecus with a posture and body plan like a gorilla. The body size estimate of Simons and Ettel was somewhat informal, based on a general appraisal of the size of jaw and assuming a proportional relationship between jaw size and body size.

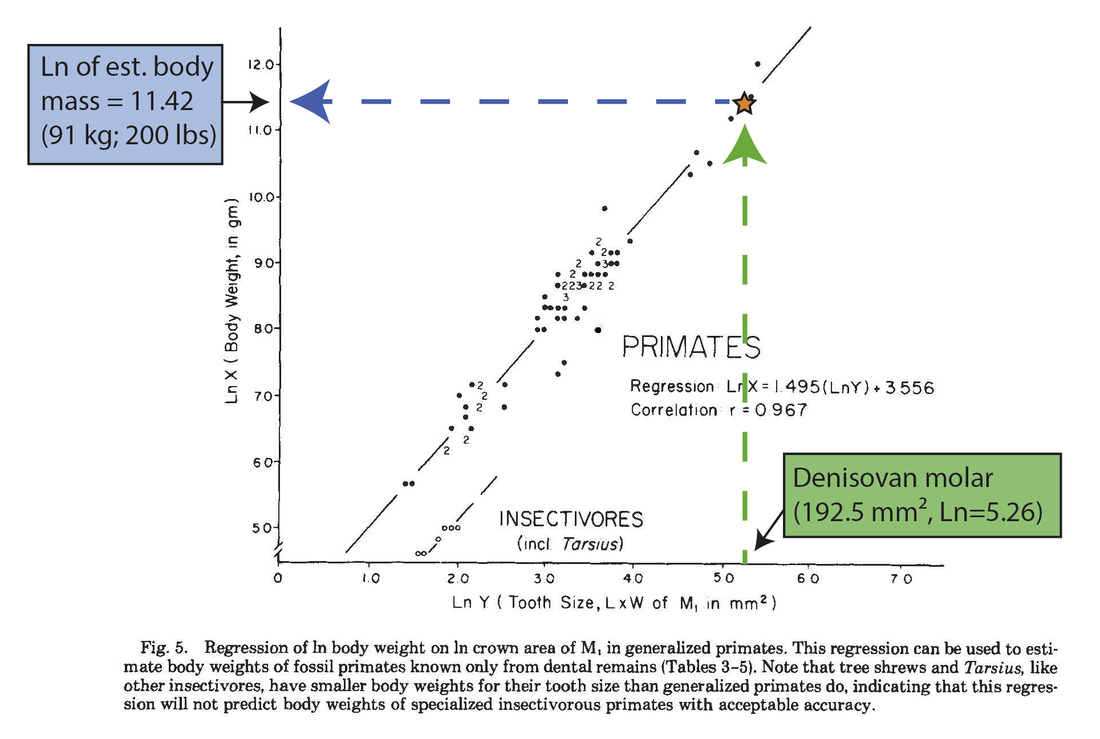

The 1980's saw the publication of studies that considered the allometry of tooth/body size relationships across primate taxa. A 1982 paper by Philip Gingerich et al. ("Allometric Scaling in the Dentition of Primates and Prediction of Body Weight From Tooth Size in Fossils") considered how tooth area scales to body weight among extant primates and used that information to estimate the weight of fossil primates. I have reproduced the figure from their paper that shows the logarithmic relationship and the regression formula based on that relationship.

"Much remains to be learned about allometric scaling of tooth size and body weight in the dentition of primates and other mammals. Our results demonstrate that there is a coherent pattern of differences in scaling at different tooth positions across the whole range of generalized primates. We have not investigated how this general pattern might change if primates were subdivided into smaller taxonomic groups or into dietary guilds."

As far as I can tell, that remains at least somewhat true today (I have yet to make a concerted effort to get into the current literature on tooth/body size scaling . . . hopefully I can get around to it soon). Although we clearly know more about tooth/body size relationships than we used to, the estimation of primate body size from isolated teeth remains problematic. While there are general relationships, they're not necessarily proportional. A big tooth doesn't necessarily mean a proportionally giant creature.

The large tooth from Denisova Cave is good example of how "big" is still equated with "giant" in the absence of other evidence. According to this 2010 paper, the Denisovan tooth (probably a second molar) is the largest human tooth ever discovered. Because of its size (and because there aren't any other Denisovan fossils that can tell us something directly about body size), it has been interpreted by the fringe as evidence of giants (I wrote a little about it here). The tooth reportedly measures 13.1 mm by 14.7 mm, giving an area estimate of 192.5 square mm. Notably, it is smaller than the corresponding teeth of some austalopithecines (who were smaller in body size than humans but had a very tough diet, and, hence, big chewing teeth). If I plug that area into the Gingerich et al. (1982) regression shown above (yes, I know it was based on areas of first molars, not second molars, but bear with me for the sake of general comparisons) I get a body mass estimate of about 200 lbs (91 kg).

Two hundred pounds: is that a giant? It's surely above average for humans today, but it's really a stretch to call a 200-lb individual a "giant." Even allowing for that 200 lbs to be an underestimate (because it's based on a second molar rather than a first molar), how do we know that the the large tooth size isn't somehow related to the evolutionary history and/or diet of Denisovan populations? There are just a few teeth to go on - that's it. Just like with Gigantopithecus, I think we've really got to be aware that we're effectively blindfolded on the issue of body size until we've got some decent postcrania to look at.

As a final note, I think it's fascinating that Weidenreich saw the East and South Asian fossil record as supporting the idea that body size decrease through time was a major trend in human evolution. That is, of course, opposite of what the African record from the last 4 million years or so has now demonstrated. Weidenreich was wrong, but he was no lightweight and no dummy. He based his ideas on the direct evidence that he had: fossils. We'll never know what he what he would have thought of the decidedly un-human Gigantopithecus mandibles that were discovered just a few years after his death, but I would bet a large sum of money that he would not have stuck with the "giant phase of Man" idea that he outlined in his 1945 monograph. Accepting that new evidence can falsify a hypotheses is part of doing science.

Weidenreich's published ideas about also give the lie to the fringe/Creationist notion that 20th century academics have conspired and are continuing to conspire to suppress the "truth" about giants in the past. Or maybe someone just forgot to send Weidenreich his conspiracy brochure. I guess that's possible, since I have yet to receive mine, either.

Next up: The history of body size estimates of Gigantopithecus.

Garn, Stanley M., and Arthur B. Lewis. 1958. Tooth-Size, Body-Size and “Giant” Fossil Man. American Anthropologist 60(5):874-880.

Gingerich, Philip D., B. Holly Smith, and Karen Rosenberg. 1982. Allometric Scaling in the Dentition of Primates and Prediction of Body Weight From Tooth Size in Fossils. American Journal of Physical Anthropology 58:81-100.

Simons, Elwyn L., and Peter C. Ettel. 1970. Gigantopithecus. Scientific American (January 1, 1970).

Weidenreich, Franz. 1945. Giant Early Man from Java and South China. Anthropological papers of the AMNH, Volume 40, Part 1.

RSS Feed

RSS Feed