Because the Type F exhibits some elements of actual sword design (though, tellingly, not Roman sword design) many people have concluded the MOAFHS was possibly a real sword at some point. However, a more specialist eye cast on the features leads me to the conclusion that at no point was the MOAFHS a real sword, thereby eliminating a whole category of objects we need to look at. Knowledge of historical European sword design elements, their function, the history of European swordmaking and craftsmanship, personal experience in examining and minutely handling 18th, 19th, and 20th century swords, and experimental archaeology in reconstructing swords of the period with fire, anvil and hammer all played a role in this assessment, that the designer of the MOAFHS wanted to visually create a swordlike appearance, but did not understand actual sword sword design or function, as you will see.

First, you need to know your terminology, as I’m going to toss out a lot of technical terms-a basic guide to sword nomenclature can be found here.

Now let’s look at the California sword and begin.

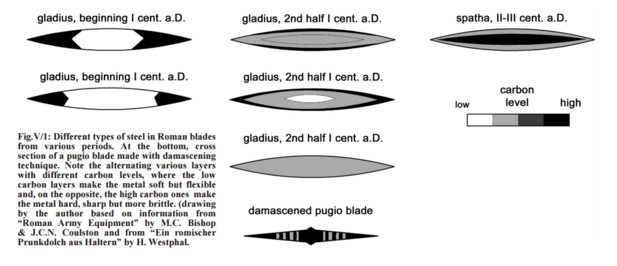

Let's start with the fullers, then. What is a fuller for? Simply, to lighten a sword while preserving structural strength, to balance a sword by moving its center of gravity, and to be decorative. Short swords designed for thrusting do not require them, which is why the Roman gladius doesn’t have them. Longer swords designed to inflict damage by cutting do, as seen in Germanic swords (the spatha, Frankish, Gothic, Anglo-Saxon, Norse, etc.), but those swords have single fullers, so no matches there. Medieval swords follow those same basic elements, since they are refinements on a cultural European consensus on what swords look like and do. Double fullers do not appear until the 17th century. Double fullers, in addition, are incredibly difficult to make-look up hand forging, pattern welding and tempering a sword and shaping a single fuller, and you will understand why that design element remained static for centuries, and why smiths were considered practically magicians. This is particularly fascinating.

Double fullers don’t really show up in European blades until the end of the 17th century, and only in very small numbers of high end broadswords created by superior craftsmen in the “capitals” of the European swordmaking craft, Toledo, Spain and Solingen, Germany. Sword technology and skill were rapidly moving into new forms-the state of the art was becoming increasingly complex. Owning these weapons was like owning a high end sports car or designer clothes or a famous work of art -- the smith even signed his work. They were expensive as hell status symbols showcasing the wealth and status of the owner, just as swords throughout the ages have, as this late 17th century basket hilted broadsword with a Solingen blade shows-but also a completely functional deadly weapon quite capable of killing.

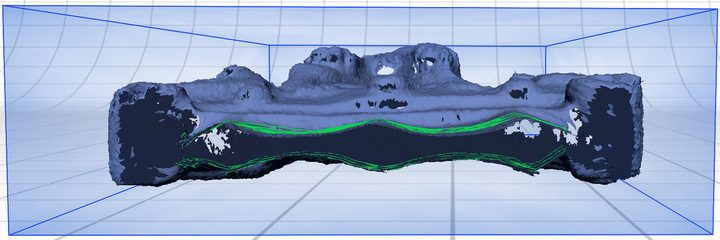

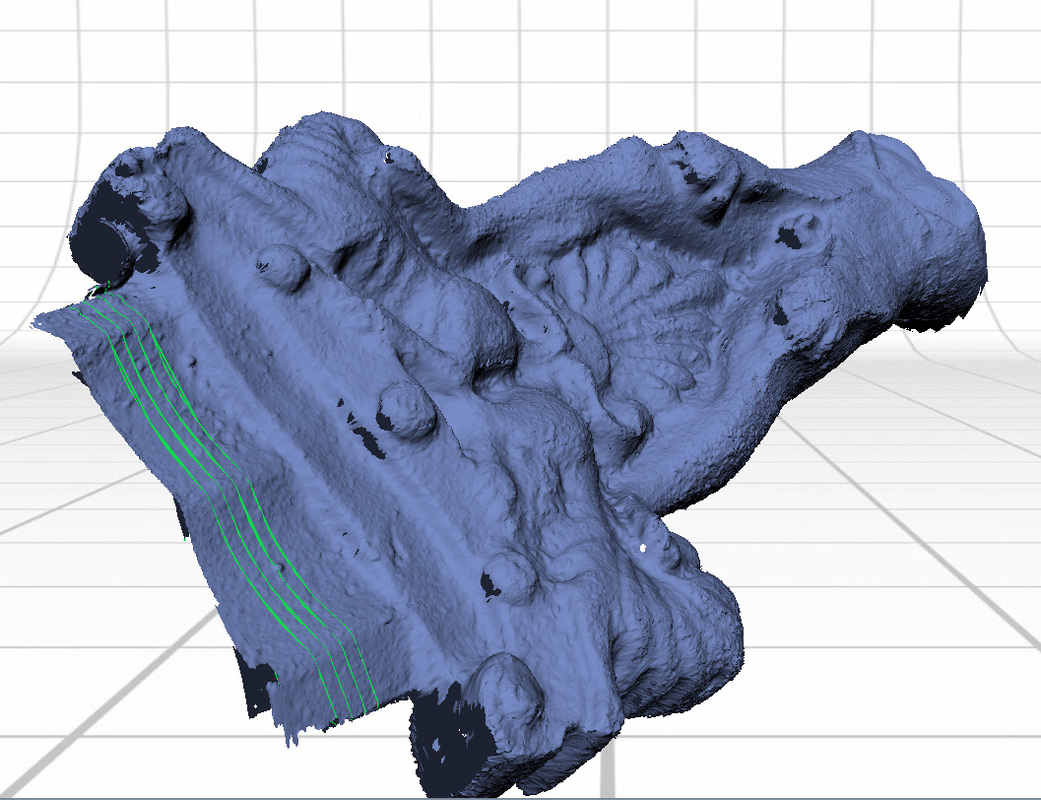

The lack of a ricasso, or potentially only a vestigial one-(it's difficult in the cast to tell what is blade and what is hilt components) again is a “100%, smoking gun” sign that we are not dealing with a real sword. Here is Andy’s scan of the California sword:

Sabers are maintaining some utility but also increasingly a vestigial remnant of a bygone era. Military edged weapons are industrialized, mass produced, not handcrafted. Swordsmiths are increasingly marginalized into producing Romantic Victorian era decorative pieces-pseudo weapons, with increasingly elaborate and useless decorative motifs, including anthropomorphic hilts, classical figures and blades that couldn’t cut fruit. These are not swords, they are objets d’art. With the disappearance of real swords from everyday life, people forgot what real swords were supposed to look like. The late 19th and early 20th also witnessed a simultaneous explosion of interest in the classical world and archaeology as a science takes a few baby steps away from treasure hunting and tomb raiding (of which Andy is more qualified to write about)-resulting in a market around the tourist trail of Roman sites for upper middle class Europeans, with a nodding acquaintance of classics but none of actual artifacts or just a desire for a cheap souvenir. Emperor Napoleon III commissions digs at Alesia, The Roman Museum at Mainz begins to assemble collections, the British Empire looks to the Roman one as a model, and Italy cashes in with tourism. The FHS fills a niche in downmarket tourist ware, created by a person who had never held a real sword in his life, and manufactured by some Italian blacksmith or metalworker who was slamming out metal in his backyard, in a 19th century analogue to these metal workers in India today, who for all we know are casting Design Toscano swords.

RSS Feed

RSS Feed