I feel you, Middle Archaic, I feel you.

Based on the looks on my students' faces during class yesterday, the lack of enthusiasm for the Middle Archaic is not limited to professionals. I'm lucky I had a few slides about the Lizard Man of Lee County to get the lecture going. It was all downhill from there. Perhaps the proximity of spring break contributed, and perhaps it just wasn't my best-prepared or best-delivered class. But I think their lack of interest in the Middle Archaic is, like that of many archaeologists, real.

Where's the love for the Middle Archaic?

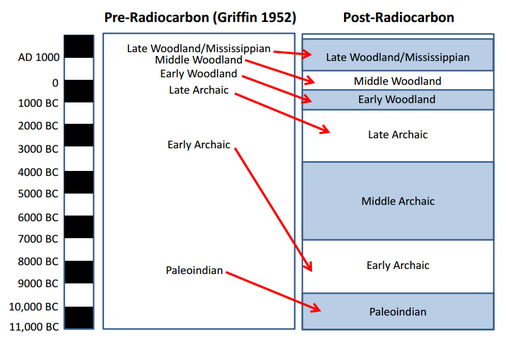

The privation suffered by the Middle Archaic is certainly not due to a lack of importance. It is the longest sub-period in Eastern Woodlands prehistory, consuming three thousand years between about 8000 and 5000 radiocarbon years before present (RCYBP) (~8900-5800 calibrated YBP; ~6900-3800 BC). While there is still much we don't understand about what happened during those three millennia, we do know that the societies that emerged at the end of the tunnel were quite different than the Early Archaic societies of the earliest Holocene. The Late Archaic world was filled with semi-sedentary societies inter-connected by webs of ritual and exchange that moved artifacts across vast distances of the east. Many Late Archaic societies were somewhat dependent on domesticated plants. There is evidence of territoriality, violence, and perhaps incipient craft specialization. The population of the Eastern Woodlands was undoubtedly significantly higher than it had been a few thousand years earlier. Between 8000 and 5000 RCYBP, just about everything changed.

The Archaic middle child, however, just doesn't rate much interest in many regions. My impression is that some of that neglect is due to the nature of the material culture -- much of the lithic technology of the Middle Archaic is just not objectively pretty. And in some parts of the country, like the Midwest, we still have difficulty identifying Middle Archaic sites based on stone tools. Either we're not recognizing the point styles as Middle Archaic or there just aren't that many sites. The situation is different in the Carolinas, where Middle Archaic sites thickly blanket portions of the landscape. It's a confusing picture that probably contributed to the Middle Archaic being unrecognized as a meaningful cultural-historical unit until after the advent of radiocarbon dating.

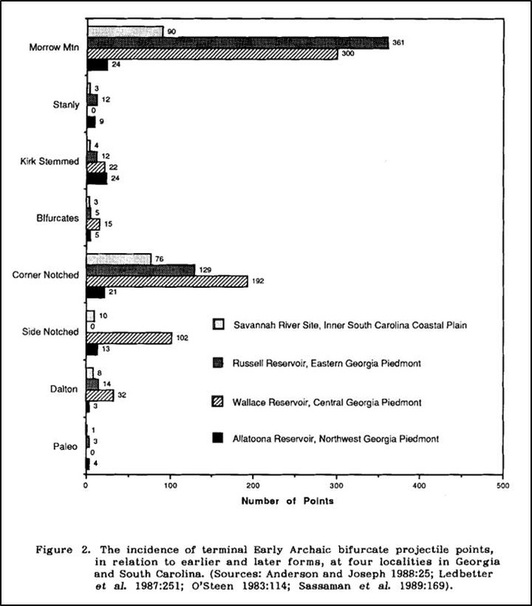

One of those is Ken Sassaman. I'm currently working my way through his 2010 book The Eastern Archaic, Historicized and finding it fascinating. Sassaman proposes that the archaeology of the Eastern Woodlands records an abandonment of significant portions of the Southeast at the end of the Early Archaic and a subsequent influx and occupation by peoples with origins outside the region (presumably to the west). Those intrusive peoples, Sassaman argues, constitute the founding populations of the Shell Mound Archaic phenomenon focused between the Tennessee and Ohio Rivers. They can be recognized by the appearance of stemmed Morrow Mountain points representing a distinct technological break from the lanceolate-notched point tradition which descends from Clovis.

First, as Sassaman acknowledges (pg. 44), migration-based explanations for changes in material culture largely fell out of favor as the adaptation/ecological focus of processual archaeology took the baton from cultural-historical archaeology.

Second, the brave new world of theory in which we now operate means that there are potentially many different ways to approach, evaluate, and flesh out the hypothesis of a major migration into the region during the Middle Archaic. Sassaman highlights, for example, some basic contrasts between the behaviors and belief systems of diasporic communities ("those that share a common history but not a common place") and coalescent communities ("those that share a common place but not a common history") and asks how we might understand the record of the Middle and Late Archaic using that lens. As someone who has spent time wrestling with Archaic lithic technologies, I like the idea that maybe there are other ways to approach the confusing space-time tangle of projectile point styles and connect changes in that tangle to other aspects of history, process, and interaction. Diasporic communities, eventful history, and ethnogenesis in the Middle and Late Archaic? Now that sounds like fun.

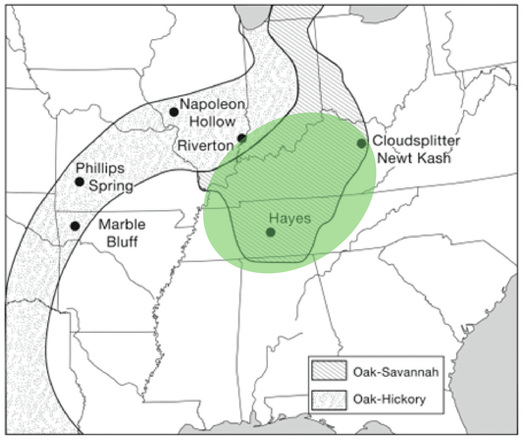

Third, a new framework for examining alternative narratives for the Middle Archaic facilitates a fresh look, I think, at the "bread and butter" questions of intensification and complexification of hunter-gatherer societies in the Eastern Woodlands. What happens to our explanations of settlement and subsistence change if we can't presume demographic (i.e., biological) continuity through time? Look at Bruce Smith's map (in this 2011 paper) of where the earliest domesticated plant remains have been recovered with the core area of the Shell Mound Archaic superimposed:

Readers of this blog know that I love entertaining so-called "alternative" ideas that run counter to prevailing interpretations but also fit the available evidence. This is a good one. As I'm reading Sassaman's book (I'm on chapter 4 of 6), I'm finding myself flipping through my internal store of knowledge, opinions, and assumptions about the Midwestern (especially Ohio Valley) Archaic that I know fairly well and the new things I'm learning about the Carolina Archaic. Any book that prompts that kind of reshuffling is, in my opinion, a good book.

There is a great amount of work to be done, and I hope that Sassaman's book stimulates some new thinking about this chunk of time. If you can read through his treatment of regionalized mortuary practices, craft and trade, and mound building and monumentality during the Middle Archaic and not be convinced that this sub-period is not only worthy of much more attention but, when viewed at a macro scales, fascinating . . . you probably haven't read this far into this blog post anyway. Sassaman's book doesn't just dress up the Middle Archaic in a rented tuxedo for the night to make it look good: it constructs a legitimate re-boot that students of Eastern Woodlands early prehistory should have a look at.

Maybe I can make my next class on the Middle Archaic a little spicier without relying on the Lizard Man. There are a lot of nuts and bolts things that we need to know about how the rhythm and tempo of Middle Archaic life at small scales (hence my interest in finding some well-preserved sites to go along with all of the surface data here). But tying those things into larger sets of questions that move beyond simple ecology (or at least considering a larger range of social and demographic settings in which to situate those ecological questions) can't hurt. Whatever happened in the Middle Archaic happened, and there's no changing that now. It's not the Middle Archaic's fault if we're not smart enough to figure it out. Don't blame the victim.

I know that some of you follow this blog are professional archaeologists and some are not. I find Sassaman's book to be very readable, but there is some technical content that probably won't appeal to all audiences. You can find the first chapter here as a pdf if you'd like to have a look.

- Anderson, David. 1991. The Bifurcate Tradition in the South Atlantic Region. Journal of Middle Atlantic Archaeology 7:91-106.

- Griffin, James B. 1952. Archaeology of Eastern United States. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

- Sassaman, Kenneth E. 2010. The Eastern Archaic, Historicized. New York: Rowman & LIttlefield.

- Smith, Bruce D. 2011. The Cultural Context of Plant Domestication in Eastern North America. Current Anthropology 52, No. S4, The Origins of Agriculture: New Data, New Ideas (October 2011), pp. S471-S484.

RSS Feed

RSS Feed