First, a quick recap. On May 10, Jason Colavito wrote this post about a mid-1700s address by Claude-Nicolas Le Cat to the Academy of Sciences at Rouen. I recognized many of the descriptions of "giants" in Le Cat's address from my stumblings through 19th century American newspapers: portions of his address, copied from somewhere, had been incorporated into stories that were circulated and re-circulated during the later half of the 1800s. As I wrote in this post, the earliest versions of the story that I could find dated to the mid-1840s and seemed to associate the listing of European giants with a lecture by Benjamin Silliman, Jr., a Yale chemistry professor. In this post, Jason worked on tracking down what may have been the origins of the story, showing how Silliman's name may have been attached (presumably by a reporter/editor somewhere) to a story with a listing of giants that was already in circulation in the 1840s. The original giants story probably originated with someone copying a portion of Le Cat's address out of an encyclopedia or other available source (the address was also printed in a Maryland newspaper in 1765 as well as other places). As the hybrid story was passed on and mutated, Silliman's name became welded to those of the giants. Many of the giants suffered great indignity as the accumulation of copying error transformed their original names into nonsense. The grand, 25' tall Theutobochus Rex, for example, had become known as Keutolochus Sex by the time the story was printed in Idaho in 1871. More on that later.

So, three days and many hours later, I've got enough data on these "Giants of Olden Times" stories to recognize some patterns. I've compiled about 220 printings of the stories so far (there are probably three of four "main" versions) dating from 1842 to 1905. I'm recording the date, the newspaper, the state, and the occurrence/spellings of several of the names in the stories as well as several key dates associated with the giants. The errors in the stories are interesting to me because they, along with information about space and time, will help track how the stories were spread through time and across space (like mutations in DNA). Understanding the mechanisms and patterns of spread will be relevant to understanding the "giants" phenomenon in general, I think. And it will also potentially shed light on how information flowed during a really interesting period of demographic, social, and technological change in the United States. For now, though, I just wanted to take a quick look at some temporal and spatial dimensions of the data I've collected so far.

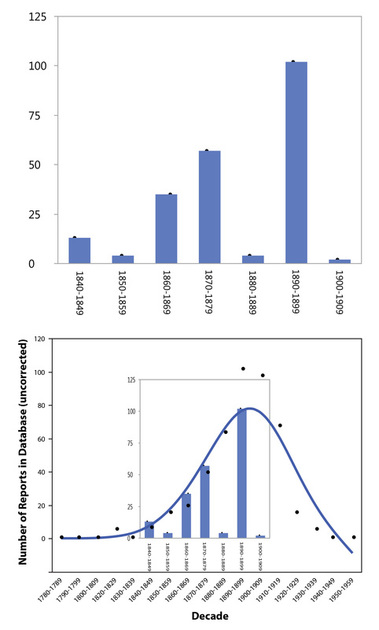

The top part of the figure to the right shows the counts of the printings of the "Giants of Olden Times" stories by decade. You can see that the distribution of the stories across the decades of the late 19th century is not uniform. After the first printings of the story in the 1840s (the first "peak") there is a lull in the 1850s followed by a large number of printings in the late 1860s and early 1870s. You can't see it in this view of the data, but there is a strong peak from October of 1868 to June of 1870. Note that the peak starts prior to the "discovery" of the Cardiff giant (and perhaps reflects the context of the interest in giants that spurred the creation of the hoax) and drops off soon after it was revealed as a fake (in December of 1869). There is an apparent lull in the printing of the stories in the 1880s, followed by a strong peak in the 1890s. I have found just a few re-printings of of the stories after 1900.

The bottom part of the figure shows the bars representing re-printings of the "Giants of Olden Times" stories placed within my data of the number of reports of "giant skeletons" in my current database. Note the general similarity in the shape of the upswing curves. And note also that the reports of giant skeletons drop precipitously after 1910-1919, a couple of decades after newspapers apparently stopped printing stories with listings of European giants.

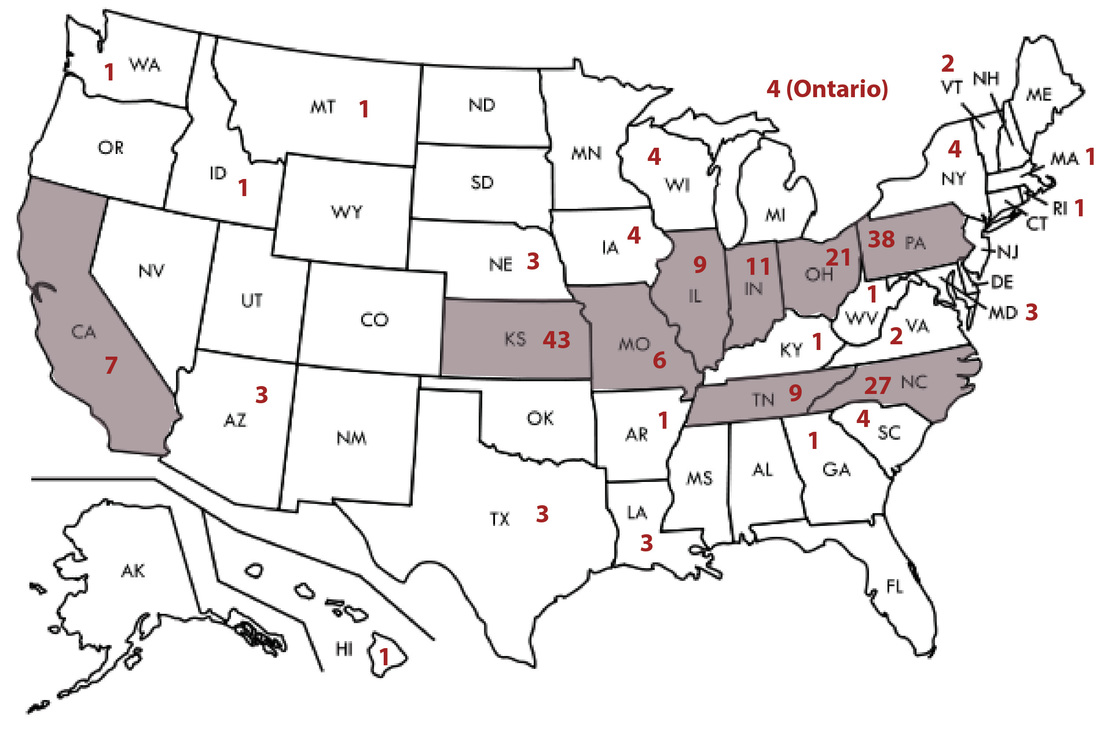

Printings of the "Giants of Olden Times" stories were not randomly distributed across the county. The map below shows the counts (in red) by state in the data I've accumulated so far. A histogram of the number of re-printings by state shows most states with less than six. Nine states have six or more (shaded in the map below). With the exception of California, those states form a kind of "Giant Stories" belt stretching from the east coast into the Great Plains. This is the region of the country where these stories were printed over and over again.

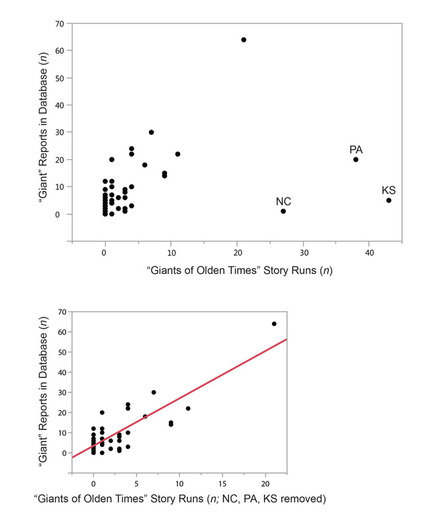

Are the "Giants of Olden Times" stories connected to reports of giant skeletons? I plotted the number of re-printings of the "Giants of Olden Times" stories vs. the number of reports of giants by state that I have in my current database. The top chart shows all the data I have so far. Two things are notable: first, the points on the left side of the chart appear to show a possible positive relationship between the number of story re-printings and the number of accounts of giant skeletons being unearthed; second, there are several outliers on the right side of the chart that don't appear to fit that relationship. I've located 43 re-printings of the "Giants of Olden Times" stories in Kansas newspapers, for example, but only five reports of giant skeletons from that state. North Carolina newspapers also loved the "Giants of Olden Times" story, but the state just didn't produce that many giant accounts (at least not that I've seen so far).

If I remove those outliers, a linear, positive relationship becomes easier to see (bottom chart). The R square is 0.69, with a p value of <0.0001. The strength of the result decreases to an R square of 0.40 if I remove Ohio (the point at the upper right), but is still statistically significant. With just these values, in other words, it doesn't look like this relationship is just by coincidence: places where the story ran more often are places where there were more reports of giant skeletons.

But the identification of this correlation doesn't tell us which way the causal arrow(s) point. Did re-printing these stories "cause" people to report giant skeletons? Or did the finding of "giant" skeletons stir up public interest and prompt newspaper editors to re-print the "Giants of Olden Times" stories? Or both? That's going to be a tricky thing to understand, but I think it may be possible to figure out it. The great thing about the newspaper accounts is that they are all dated, so it will eventually be possible to understand the temporal ordering of events. It will also be possible using GIS to factor both time and space into an analysis and frame it in terms of the changing technology of media communication. This is great problem and will take some time to deal with, but I think it is probably solvable. And I think it will ultimately be an important part of the puzzle of "giants" in 19th century America.

RSS Feed

RSS Feed