I've had the opportunity to show it to a few of my colleagues at SCIAA and create a 3D model with a laser scanner. I also plan to get metallic composition data, probably using a scanning electron microscope. It's fun to carry the sword up and down the hall. I may not send it back. (Don't worry, that's a joke: I'm going to send it back. Eventually. Some day.)

Anyway, as I said earlier today, I'm finding the challenge of understanding the mystery of the origin and history of these swords becoming more interesting than the "is it or is it not Roman" question. I've seen no credible evidence so far that suggests to me there is much more than a snowball's chance in hell that the Nova Scotia sword is an authentic ancient Roman artifact. Nothing about the story makes much sense, and we haven't yet been given the promised details that will demonstrate to us that this is a "100 percent confirmed" Roman artifact. The hypothesis that the Hercules-hilted brass/bronze swords (perhaps 7-8 known now) were produced as souvenirs within the last few centuries accounts for all the information about these swords that we currently have. It's the strongest hypothesis going at this point. I wanted to take some time today to flesh it out with a few more insights related to the California sword.

A lot of people contributed to my thinking for this post. Many people have commented on my blog and sent me emails with observations and tidbits of information, and I want to acknowledge all of those contributions. Please let me know if I used your idea or information but didn't give you credit for it. There has been a lot going on on this blog and in this story for the last week, and it's hard to keep up with it all. I also want to thank Jim Legg and Chester DePratter, two of my colleagues at SCIAA, for taking the time to look at the California sword, share their insights, and help me think my way through some issues this week. I told them that I was going to mention their names but retain for myself the full responsibility and ownership of any dumb ideas. These guys have a lot more relevant expertise than I do, and I'm happy that they found this to be an interesting problem.

Bear with me here -- this could be long. Also, if you have any expertise in swords or metal casting and you'd like to tell me if I've got something wrong, I'd love to hear it. Please leave a comment.

They Are All "Copies"

It's clear that we've got a lot of swords now that were made from the same mold or are copies of swords made from the same mold. Here's a comparison of six brass/bronze swords plus the iron Design Toscano sword. (As an aside, I don't think the proponents of the "Roman sword from Nova Scotia" claim were at all prepared for how many of these things would surface once people were looking for them. If they had known that there were were a lot of copies floating around, they presumably would have been prepared for that information and not had to scramble to make up a sequence of baloney stories about Photoshop, plastic swords, the Emperor of Rome issuing a set of ten, etc.).

All the swords are "copies" in that they were all cast - the similarities in the figures make that obvious. Molten bronze, brass, or iron was poured into a mold that was created using some object. Even the very first sword, then, was a copy of some original object.

Which Copies Are Earliest?

Determining which swords are the earliest would be of immense help in unraveling this story and finding the original object.

Proponents of the "Roman sword" claim propose that there was some "original" ancient Roman mold that was used to produce several of these swords. Because they claim the Nova Scotia sword is an authentic Roman sword (and not some cheap copy), we can presume that that sword is exactly how it's supposed to be: it is supposed to be a high quality item that was made by Commodus and dispensed to his special legion commanders while supplies lasted.

Do the data we have support that? I don't think so.

Because of the error that accumulates as copies are made of copies, one would expect that swords from later generations (i.e., Hercules-hilt swords that were not produced in ancient Rome) would be missing some of the details present on the authentic Roman swords. This leads to a key expectation: other things being equal, the earlier the sword, the more it should look like the original. In reality, of course, one can't really make all other things equal (such as wear during the life of sword, natural variation in quality, etc.), but, as I will discuss briefly below, I don't think that issue matters much to my argument. Note: if some later copies are made from going back to the "original," that would compromise the negative relationship between time and "faithfulness" that is created by accumulations of copy error.

To find the earliest sword, then, we look for the one that has design details and features that were not preserved in subsequent generations. And, lo and behold, that's the California sword. And, interestingly, those design details and features are in the blade, not in the figure of Hercules. The blade is the key. I think it all but eliminates the possibility that the Nova Scotia sword is an authentic Roman artifact.

Why? Because it's not the same as the Nova Scotia sword blade, but it's the exact opposite of what one would expect if it was a copy. The California sword has a blade that appears to be unique among the swords. Assuming all of these swords are somehow related, which I think is pretty clear at this point, the most plausible explanation for the presence of features on the California sword blade that are absent on all the swords is that it is earlier in the copy chain than those swords. The overall high level of detail on the California sword (high enough to clearly show that interpretations of design elements in the Nova Scotia sword are nonsense) is consistent with that idea.

The Blade of the California Sword

As far as I can tell, the blade of the California sword is the only one we know about that has grooves in the blade called fullers (apparently the term "fuller" is used to refer to both the tool that the makes the grooves and the grooves themselves). Fullers are used to lighten the blade while preserving strength. They are a common feature of real, functional swords. The California sword has a double fuller cross-section: two fullers on each side.

The guard and proximal blade of the California sword.

The guard and proximal blade of the California sword. When I first saw this sword, I thought maybe it had been broken and repaired by replacing the missing portion of the double fuller blade with a lenticular blade. It struck me as notable when they mentioned on television that the Nova Scotia sword also appeared to have been broken and repaired.

When Jim Legg looked at the sword, however, he told me he thought it was cast as a single piece. His opinion was that the Hercules figure and the fullered part of the blade may have been cast from a mold of the original object while the un-fullered part of the blade was produced using a separate piece in a sand mold. There are some small cracks where the fullered and un-fullered portions of the blade meet, and there seems to be a gray putty-like substance under the patina as if the maker tried to blend the interface of the two sections.

If the "original" was a sword with a fullered blade and the Nova Scotia sword doesn't have fullers . . . it's game over for the "Roman sword" claim. I think it's completely implausible to say a later, farther-down-the line copy is going to have a detail like fullers that the original "Roman swords" do not. Explain to me how that could have happened. It's not a small detail that could just come and go. And why would you add a detail like that to a portion of of the blade of a non-functional reproduction? I think the fullers were on the original. And because there are no fullers on the Nova Scotia sword, it ain't one of the "originals."

Legg suggested to me that the figure and fullered blade portion may represent the "original" artifact. Maybe if there is an original sitting in a museum or collection somewhere, it's just the hilt and a bit of the blade rather than a complete sword.

Should We Assume the Original Was Copper Alloy?

Short answer: no.

Since this debacle began about a month ago, I've been operating under the assumption that I was probably looking for a one-piece bronze or brass "original" sword. But after thinking about the California sword as maybe the closest to the original we've seen so far, I think it's wise to discard that assumption.

It's possible that the three raised circles on the guard represent the rivets on the original sword that were used to attach the blade to the hilt assembly. They're present on both sides (as you can see on the 3D model). The central ones are the largest, measuring about 6.1 mm in diameter and raised about 1.8 mm above the guard. The outside circles are about 5 mm in diameter.

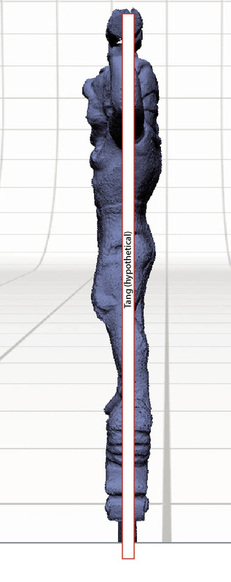

If the blade and the hilt were separate components on the original, there would have to be a tang of some length that would allow the parts to be connected. The side view of the 3D model of the California sword shows that there is probably sufficient volume inside the Hercules to have had a full or partial tang. The hilt is solid in a line all the way from the guard to the club above Hercules' head. The need to have a solid mass for a tang might explain, in fact, why there's a palmette between his legs (instead of empty space) and why the tail of Hercules' lion skin is where it is. A tang could have extended all the way through Hercules' head up into and through the club. (I'd like to be able to measure the front-to-back thickness of the palmette, but I don't have the calipers to do that in my office right now.)

I don't know enough about sword construction to know if three rivets on the guard would be the only direct signs of composite construction.

That's the question I'd really like to answer. There's no solution yet, but there are some tantalizing leads.

Everyone agrees, I think, that there's no way this was a normal military sword. The "Roman sword" people say it's a ceremonial sword, either given away to those very special legion commanders so they can use its magical powers to navigate to Oak Island, or perhaps used in some kind of gladiator-related ceremony. Neither of those sound very likely to me, and I have yet to hear a Roman antiquities expert endorse either interpretation as plausible.

"A hunting sword is a type of single-handed short sword that dates to the 12th Century but was used during hunting parties among Europeans from the 17th to the 19th centuries. A hunting sword usually has a straight, single-edged, pointed blade typically no more than 25 inches long. This sword was used for finishing off game in lieu of using and wasting further shot. Adopted by many Europeans, and in past centuries sometimes worn by military officers as a badge of rank, hunting swords display amazing variety in design."

The "amazing variety in design" is important. Do a Google image search on "hunting sword" and browse through the results. You'll see some pretty plain swords, but you'll also see swords with very ornately carved grips, including some with human figures. Here's one with a carved ivory lion as a grip. Here's another ivory grip with a bunch of different animals on it. Here's one with Hercules cast in silver. These swords are functional, but their restricted use means they can be a lot fancier than their workaday military grade counterparts.

My friend Jeff Plunkett introduced me to the idea of a hunting sword when he emailed me with this description of of a hunting sword taken from page 242 of the National Exhibition of Works of Art at Leeds 1868:

"SHORT HUNTING SWORD, the grip and cross guard in chiselled steel, the grip representing a figure of Hercules clad in the lion's skin, the cross guard of two dragons. Italian--17th century."

There's no image of the sword. Someone want to try to track one down or figure out where this sword currently resides?

That particular Italian hunting sword may end up looking nothing like our guy, of course, but it would be interesting to see nonetheless. It's proof that people were, in fact, producing Hercules-themed hunting swords in during the last several centuries. It's possible that one of those was the "original" for the Hercules-hilted swords we're so fond of discussing today. In other words, just because it has Hercules on it doesn't mean it's Roman.

What Next?

We know that Hercules had good symbolic cred in many parts of Europe and the Mediterranean, and I think it's likely that the "original" sword is from somewhere in that vicinity. I know of no positive evidence that the original resides in the Museo Archeologico Nazionale di Napoli as asserted repeatedly by "Roman sword" proponents. In fact, I've now seen several statements to the contrary by people who are familiar with Roman antiquities and that museum. It's put up or shut up time for the claim that an original lurks in a museum in Naples. I call BS: what say you?

But I think it's possible that the original may have been in that museum in the past. This is all speculation on my part, but I wonder if it's possible that a later hunting sword kept in the Naples Museum was, at one time, mistaken for a more ancient artifact? I'm not just pulling this idea out of thin air, but seeing it as a possibility based on this incredibly interesting article (supplied by Chester DePratter) about sleuthing out real/replica bronze swords from Scotland. There are a number of similarities between the case discussed in that paper and the one we have on our hands, and there are also some interesting differences. The point I'd like to make now, though, is that the article shows that museum curators, even in the mid-1800's, could not always recognize what was and was not Roman! It's possible that some later weapon was cataloged as "Roman" in a museum (perhaps simply because it had Hercules on it) for some time, and perhaps even displayed as such. Maybe replicas were made of the "Roman" weapon for a while before the item was reclassified or retired within the museum. Outside the museum, however, production of souvenir swords made with the label "Gladiator sword of Pompeii" could have continued well after the museum corrected its error. And could still be continuing today. Again -- pure speculation, but, I think, plausible.

To sum up, I think you can make a good case that the California sword is the earliest one we've got, or at least the most faithful copy of the original. The lack of fullers on all the other swords suggest there were manufactured farther down the copy chain, after that functional detail disappeared somewhere along the way. The creation of the blades using a sand mold explains why they differ in length, and why some may appear to have a break or join line in the portion of the blade nearer the hilt. I don't fully understand how the molding process could have worked to simultaneously produce the blades using a sand mold and the hilt using a different kind of mold, but I'm hoping someone will tell me. (Update: see comments below).

So maybe we're looking for a composite weapon with a steel, double fuller blade and cast or carved hilt. Perhaps it will be a fragment of a hunting sword.

The $50 reward for information leading to the arrest of the original Hercules-hilted sword still stands.

This was very long. I need to eat dinner now.

RSS Feed

RSS Feed