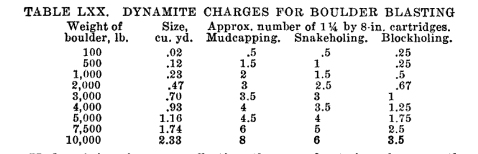

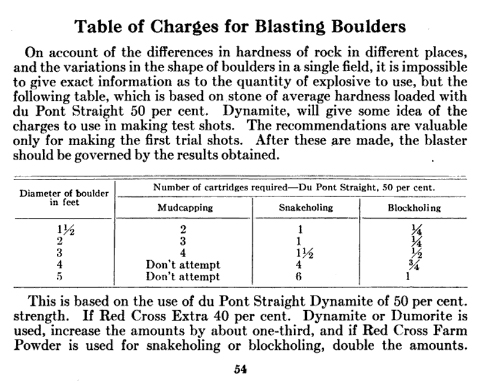

Some of the sources provide data estimating the charges required to break up rocks of particular sizes, noting that the greater power of dynamite allows one to either: (a) use less of it in a hole bored into the rock; or (b) demolish the rock without even drilling a hole (i.e., by "mudpacking" or "snakeholing"). The 1922 manual says that the charges listed should be doubled if "Red Cross Farm Powder" (which I'm guessing is some kind of non-dynamite blasting powder?) is substituted for dynamite.

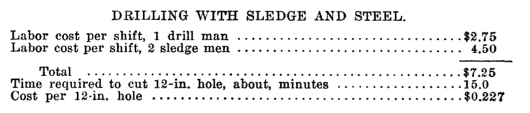

The 1916 publication estimates that a three-man crew (i.e., a "double jack" crew with one person holding the drill and the other two swinging sledgehammers) can produce a 12-inch hole in 15 minutes. I'm guessing that's appreciably faster than most of probably conceive of manually drilling holes into hard rock. If you want to see some really fast hole production, watch some YouTube videos of people competing in creating holes using mid-1800's technology: a stone drill, a 4-lb. hammer, and muscle. (Here is a short video of champion driller Emmit Hoyl talking about making holes in stone).

I'm still gathering information. My working hypothesis so far, however, is this:

Early Euro-American settlers of parts of Minnesota (moving into the area around the 1840's) would have encountered a landscape filled with glacial boulders of various sizes. Those boulders would have been a source of building stone as well as an impediment to cultivation. Some of the boulders would have movable as-is by horse and human power. Others, however, would have been impossible to move without first breaking them down in size. They could have accomplished that size reduction by explosive and non-explosive techniques, both of which would include the drilling of holes using stone drills (the straight bits of which, as we have seen, naturally produce triangular rather than perfectly round holes). Prior to 1867, gunpowder would have been the only available explosive. Holes would have been drilled into the tops of boulders to receive a charge of gunpowder. Depending on the size of the rock (and the experience of the person performing the work), blasting attempts may have regularly failed. I'm guessing that some of the intact stone holes may represent those failed attempts to blast using gunpowder. Some early (i.e., pre-1867) attempts to clear fields using explosives may have been largely unsuccessful, especially if the large boulders were mostly buried. Some of those fields may have been re-visited when more powerful explosives became available, while some apparently were not. New immigrants to the area in the late 1800's would not have had any direct memories of the earliest attempts to clear the land. Their choices of which fields to clear may have been influenced by slightly different economic conditions than confronted the earliest Euro-American settlers, and they would have been armed with a better blasting technology (i.e., dynamite).

| Transactions of the Essex Agricultural Society (1876:129) ". . . The explosive I now use is Rendrock, an admixture of gunpowder while in a pasty state with nitro-gylcerine. This powerful explosive, though well known and very generally in use by contractors on public works, is yet so little known by farmers in general that I think it will be worth while for me to give them an introduction to it, as its use enters so largely into the economy of handling boulders. " . . . As will be seen, it is over twice as costly as common blasting powder, but, as every farmer knows, the great cost in blasting is the drilling, and this is where the saving comes, as it will do as much execution as gunpowder in a hole of one-third capacity. . . . The extra power becomes of value in enabling one to do in a single blast what gunpowder would require two to accomplish." |

| The New International Encylopaedia (1905:163) "The first attempt to blast rock by the use of an explosive is commonly credited to Martin Weigel, a mine boss at Freiberg, Saxony, and is said to have occurred in the year 1613. . . . it is certain that by 1634 to 1644 the use of gunpowder in mining operations was quite generally known in Germany. From that country the process was taken by German minders to England in 1670, and to Sweden in 1724. Until 1685 the drill-holes were stopped with wooden plugs, but in that year clay-tamping was employed in Saxony. In 1791 sand-tamping was first used. Hand-drilling with cone and crown drills was used until 1759, when the modern chisel-edge drill was introduced. . . . In 1863 nitroglycerin, and in 1867 dynamite, were first used as explosives in blasting operations. . . . "Modern blasting operations may be divided into three classes: (1) small-shot blasting, in which comparatively small volumes of rock are moved at a single blast; (2) blasting by mines, in which large masses of rock are broken up by a single heavy blast; and (3) surface-blasting, in which the explosive is placed on or against, or simply near to the rock to be broken up, and which is possible only with very high explosives. Small-shot blasting is employed in the great majority of quarrying, mining, and engineering operations. It consists in piercing the rock with a comparatively small number of drill-holes from 1 1/4 inches to 3 inches in diameter and from 18 inches to several feet in depth; charging these holes with explosives, generally blasting powder or dynamite, with the proper fuse or electric-wire connections; tamping the space above the explosive with earth, sand, clay, or water, and finally firing these charges by means of a time-fuse or wires from an electric battery or magneto-machine. The relative location of the drill-holes, their size and depth, and the amount of explosive used vary according to the object which it is sought to accomplish by the blast. Where the purpose is merely to break up the rock in the most efficient manner for its removal, as in excavating a foundation, the holes will be placed quite close together and heavily charged, so as to shatter the rock thoroughly. In quarrying, where the object is to loosen the rock in large and regularly shaped masses, the holes are arranged in rows and lightly charged, so that the explosion will split the rock along approximately definite lines without shattering it." |

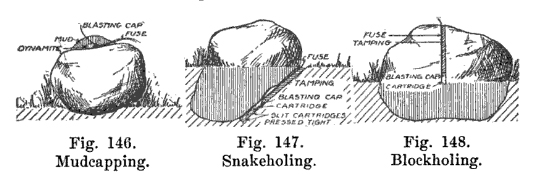

| Handbook of Rock Excavation (1916:636-637) "There are three ways of breaking up a boulder with explosives: (1) block-holing; (2) mud-capping; and (3) undermining. Block-holing consists in drilling a shallow hole in the boulder and exploding a small charge of high power explosive in the hole. Mud-capping, or "bulldozing," or "adobe (or dobe) shooting" consists simply in firing some dynamite on top of the boulder, after covering it with a shovelful of earth, preferably wet clay. Undermining or "snake holing" consists in boring a hole in the earth and firing a charge of dynamite in the hole directly beneath the boulder. Block-holing is obviously the most effective way of using the explosive. It is surprising how small a charge of 75% dynamite in a block hole will break a huge granite boulder. The cost of drilling is greatly reduced wherever pneumatic hammer drills are used. . . . A Du Pont catalog contains Table LLX giving chages of 40 to 60% dynamite for boulder blasting." "Figs. 146, 147 and 148, illustrate the proper methods of mudcapping, snakeholing and blockholing. The tests described below, carried on by the Bureau of Mines, were made to determine the comparative energy expended by explosives under water and in the air, and by various methods of shooting. The test showed very conclusively that the block-hole method of breaking boulders and large fragments of rocks is very much superior to and more economical than the mud-cap or "adobe shot" method of breaking, which is so commonly practiced." "Block Hole Drilling. Comparative methods and costs as stated by Mr. Charles C. Phelps in Engineering and Contracting, April 7, 1915." |

| Farmer's Handbook of Explosives (1922:54) |

RSS Feed

RSS Feed