In this post, I’m going to discuss two more instances – one historical and one current – where mastodons and “Mound Builders” are mingled.

The historical one (the ideas of Frederick Larkin) illustrates some of the imaginative thinking that flourished in the 19th century in a relative vacuum of temporal control over archaeological and paleontological information. The current one (the ideas of Joe Taylor) illustrates the willful disregard of almost everything we’ve learned about time in the past century. Both relate to the question of who built the mounds, enclosures, and other earthen monuments of eastern North America.

That question was answered long ago: it was indigenous Native Americans. This was established to the satisfaction of most scholars with the publication of the Bureau of American Ethnology’s (BAE) Annual Report of 1894. While our understanding about how, when, and why these earthworks were constructed has been significantly refined over the last century, no direct evidence has surfaced which suggests that the main conclusion of the BAE report was incorrect. The earthworks of eastern North America were built by and for Native American societies.

The notion that Native Americans could not have built the large and/or complex earthen structures dotting the landscape has a long history in this country that continues to this day. The 19th century question of the identity of the “Mound Builders” had a distinct racial component, with many Euroamerican observers unwilling to accept the idea that earthworks were built by the ancestors of the indigenous peoples that they had recently exterminated or forcibly removed from the region.

I suspect that, once I have my database assembled and cleaned up, I will be able to demonstrate a connection between the frequency of reporting of “giant” skeletons from the earthworks of eastern North America and the historical trajectory of the “Mound Builder” controversy. Many (though not all) of those 19th and early 20th century newspaper accounts of large skeletons employ the language of race and make explicit statements about the identity of the skeletons that can be understood in the context of the debate about the existence of a pre-Native American people/race/civilization that built the earthworks.

The current resurgent interest in giants is clearly connected to a revitalization of the myth of the “Mound Builder.” The articulation between current “research” on giants and the “Mound Builder” myth is made obvious through the "Stone Builders, Mound Builders and the Giants of North America" website of Jim and Bill Vieira and the content of their program Search for the Lost Giants. Here is a blog post by archaeologist Stephen Mrozowski explaining his view of what that program is about.

More about that later. Let’s get to the mastodon connections.

The American mastodon (Mammut americanum) was a cousin of the elephant that lived in North America for several million years during the Pliocene and Pleistocene. Mastodons became extinct as modern environments emerged after the last Ice Age: the youngest mastodon I am aware of dates to about 10,700 BC. Environmental change and human predation probably contributed to the demise of the species, though the relative importance of these factors is a subject of a debate.

What did mastodons have to do with "Mound Builders?" In reality, nothing.

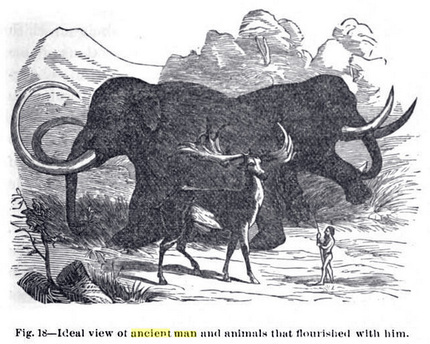

An illustration from Frederick Larkin's "Ancient Man in America" (1880).

An illustration from Frederick Larkin's "Ancient Man in America" (1880). Our first case comes from the 19th century.

Frederick Larkin, a consort of T. Apoleon Cheney in the exploration of various earthworks in New York (including the Conewango Mound), thought that the “Mound Builders” of eastern North America had used domesticated mastodons in their construction activities. He did not believe in giants. Like many giant enthusiasts (and ancient alien theorists), however, he didn’t think the earthworks could have been built by normal humans. In his sole publication, Ancient Man in America (1880), Larkin wrote:

“My theory that the pre-historic races used, to some extent, the great American elephant, or mastodon, I believe is new and no doubt will be considered visionary by many readers and more especially by prominent archaeologists. Finding the form of an elephant engraved upon a copper relic some six inches long and four wide, in a mound on the Red House Creek, in the year 1854 and represented in harness with a sort of breast-collar with tugs reaching past the hips, first led me to adopt that theory. That the great beast was contemporary with the mound builders is conceded by all, and also that his bones and those of his master are crumbling together in the ground.” (preface)

“From the shores of Lake Superior we can trace this people to Wisconsin, where we find some singular earthworks: six effigies of animals, six parallelograms, one circle, and one effigy of the human figure. These tumuli extend for the distance of half a mile along the trail. What the animals represent in effigy is difficult to determine. Many at the present time suppose that the mastodon is one, and that he was a favorite animal and perhaps used as a beast of burden. That the mastodon was contemporary with the mound-builders is now an undisputed fact. It is a wonder, and has been since the great mounds have been discovered, how such immense works could have been built by human hands. To me it is not difficult to believe that those people tamed that monster of the forest and made him a willing slave to their superior intellectual power. If such was the case, we can imagine that tremendous teams have been driven to and fro in the vicinity of their great works, tearing up trees by the roots, or marching with armies into the field of battle amidst showers of poisoned arrows.” (page 3)

Later in the volume, Larkin further explained the rationale for his conclusion:

“I have heretofore suggested that the ancient Mound Builders were contemporary with the mastodon and that in all probability they tamed and used that powerful beast to haul heavy burdens. As I stand almost alone, in relation to that theory, I will give my evidence for such a belief. It is a fact admitted by all familiar with pre-historic discoveries that the bones of the mastodon and those of the Mound Builders are found in the same localities, and in about the same state of preservation; also in and around their great works, stones are frequently discovered with animals engraved upon them which are supposed to represent that animal. The copper relic, formerly referred to, found on the Allegany River with the form of an elephant engraved upon it, represented in harness, first attracted my attention to that subject. If the ancient people in North America tamed that great beast it is very likely that the inhabitants of South America done the same thing.” (pg 141)

“When we consider the magnificent works built by these ancient people it looks impossible that they could have been built by no other than human labor. The great mound at Cahokia, Illinois, is estimated to cover twenty millions of cubic feet of earth, which was all brought from a distance. Now, it would take one thousand men nearly twenty years to perform the labor which was bestowed upon building of that one tumulus, and when we consider that that is but one of about sixty other structures by which it is surrounded, one thousand men could not have performed the great labor in the days and years allotted to human life.” (pg. 143)

Given what was known about the paleontology, geology, and human prehistory of eastern North America in 1880, we should cut Larkin some slack. The idea that global cooling cycles (i.e., Ice Ages) had occurred and affected the environment was relatively new, and estimates for the age of the Earth varied from the short (i.e., ~6000 year) time frames supplied through biblical calculations to ages in the tens to hundreds of millions of years calculated based on the Earth’s temperature (Thomson) and the size of the sun (von Helmholtz). Radiometric dating techniques allowing the ages of geological deposits, Pleistocene fauna, and archaeological deposits to be estimated in absolute terms were still decades away. In other words, assuming that humans and mastodons were contemporary in eastern North America was not such a crazy thought – it was in fact correct. But we now know that mastodons went extinct thousands of years before the earliest known North American mounds were built (about 3500 BC or so).

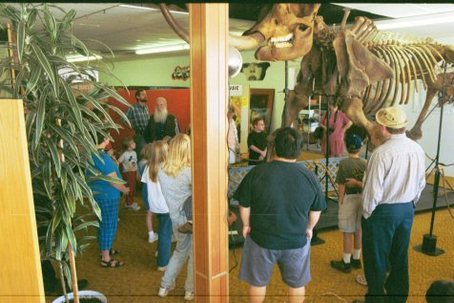

A cast of the Burning Tree mastodon on display at the Mt. Blanco Fossil Museum. Joe Taylor says the mastodon was skinned by giant humans associated with "Mound Builders."

A cast of the Burning Tree mastodon on display at the Mt. Blanco Fossil Museum. Joe Taylor says the mastodon was skinned by giant humans associated with "Mound Builders." Speaking in 2012, Joe Taylor (promoter of the 47” femur) deserves much less slack than Larkin for his ridiculous statement about the relationships between mastodons and “Mound Builders.” In this interview (about 24:00 minutes in), Taylor says the following:

“I’ve got the Burning Tree mastodon here that was skinned. I’ve got the skeleton – a cast of it – and I lived with that thing for five months so I know it pretty well. That thing was skinned. If you figure an elephant hide weighs around 2000 pounds, you have to do some tall explaining to say why would the Indians as we know them have skinned that thing. But if you know that Ohio, at Newark, where this mastodon came from, was called the Mound City . . . and if you know that in some of those mounds in Ohio there were men ten feet tall found, and others nine feet tall, now you begin to see that well, maybe if there were tribes of these men that were ten, twelve feet tall, and like the Pawnee said they were fifteen feet tall, well a half dozen or so of those guys could look at this mastodon who’s been injured and standing over there in a pool, well they’d just wait till he died and skin him. A man twelve to fifteen feet tall could actually utilize an elephant hide for armor or clothes or whatever. So I think the Burning Tree mastodon indicates that there giant men living in Ohio.”

So there you have it: according to Joe Taylor, giant Mound Builders skinned the Burning Tree mastodon. The alert listener will notice that the giants in Taylor’s story grew from ten feet to fifteen feet tall in less than two minutes. We’re lucky it was a short segment of the interview: if it had gone on for ten more minutes they would have broken the 60 foot threshold and someone would have to make a new version of that chart that’s all over the internet comparing the different skeleton sizes.

Taylor is correct that there is evidence of butchery on the Burning Tree mastodon. Everything else he says, however, is wrong. The authors of the analysis (Fisher et al. 1994:51) make the following conclusion:

“. . . the Burning Tree mastodon died elsewhere and was disarticulated and to some extent defleshed before being transported to and submerged in the pond. The patterning of marks on the bones indicates a deliberate strategy of carcass reduction involving symmetrical treatment of paired anatomical regions. The occurrence of bones in three discrete concentrations composed of anatomically unrelated units indicates intentional emplacement. The excellent preservation of bone, the presence of articulated skeletal units, and the presence of a section of the mastodon’s intestine containing viable enteric bacteria indicate that the carcass units were submerged in the pond shortly after the death of the mastodon. This constellation of factors is most parsimoniously explained by Paleoindian butchery and subaqueous caching of the mastodon’s carcass.”

The mastodon didn’t die in the pond – disarticulated parts of it were dragged there after death. And it wasn’t just skinned – it was butchered. The Burning Tree mastodon is securely dated to around 11,400 BC, many thousands of years too early to have anything to do with the Woodland period cultures that constructed the earthworks in the same vicinity. Elephants were butchered by Paleoindians (and possibly earlier peoples) in eastern North America, and were also butchered in other parts of the world during the Pleistocene. The idea that only giant humans could butcher an elephant is silly. Here is a video showing a bunch of modern people using knives to butcher an elephant carcass. None of the persons appears to be a giant. They do use a tractor at one point to turn the carcass over, but I’m sure that there are ways to process the entire carcass that don’t require an internal combustion engine.

I’m not sure how Taylor justifies completely ignoring the dating of the Burning Tree mastodon – maybe it’s because he believes the earth is only 6000 years old and therefore all information from radiocarbon dating is meaningless? The Mt. Blanco website states that the presence of living bacteria in the stomach contents of the mastodon means it couldn't be as old as the radiocarbon dates indicate. I'm not a bacteria specialist, but apparently being in a state of dormancy for a few thousand (or million) years is not a big deal for bacteria.

For whatever reason, Taylor seems to be willfully embracing the fundamental lack of temporal information that handicapped Larkin. In Larkin’s case, the lack of temporal control was due to an actual lack of information, causing him to equate proximity in space with equivalence in time. In Taylor’s case, however, there is no excuse. You have to squeeze your eyes shut really hard these days to make the same mistake Larkin did.

Taylor’s interpretation of the Burning Tree mastodon is illuminating for just that reason. There is a determined blindness at the core of the entire revitalization of the “Mound Builder” myth. In order to presume that there was such a thing as a single “Mound Builder” race or culture, you have to disregard a century of scientific archaeology and consciously flatten time in a way that hasn’t been remotely defensible since the dawn of radiocarbon dating in the 1950s. It is reasonable to ask why so many giantologists seem so willing to put those blinders on and so resolved to resuscitate an inherently racist idea that was discredited over a hundred years ago.

_______

Fisher, Daniel C., Bradley T. Lepper, and Paul E. Hooge. 1994. "Evidence for Butchery of the Burning Tree Mastodon." In The First Discovery of America, edited by William S. Dancey, pp. 43-57. The Ohio Archaeological Council, Columbus, Ohio.

_______

RSS Feed

RSS Feed