I'm not sure exactly how to interpret the modifier "rather," but I can tell you that there has been no "refusal" to investigate the pre-Clovis occupations of North America for decades now. But don't take my word for it, have a look at published papers on the pre-Clovis lithics from Gault site and the Debra L Friedkin site (Texas) or the pre-Clovis occupations at Page-Ladson (Florida). Or look at the landmark 1997 declaration on the antiquity of Monte Verde in Chile. Or the many other sites that have been put forward as candidates for pre-Clovis sites in the Americas.

It is my impression that there is now neither a stigma attached to nor a "dogma" (take a drink!) preventing archaeologists from looking for and investigating possible pre-Clovis sites.

Just because pre-Clovis is a legitimate thing to investigate, however, does not mean that every site that is claimed to predate Clovis has been interpreted correctly. Figuring out which ones pass the smell test and which do not is important if you want to get the story right. As I tell my students: adding more weak coffee to already weak coffee does not make strong coffee (I stole that from someone and I can't remember who -- I apologize).

So it matters what evidence you accept and use to build your narrative. I wonder, does Graham Hancock include the Calico Early Man Site (California) in his analysis of the human occupation of the Americas? The purported "artifacts" from the site have been said to date to 200,000-135,000 years ago. The materials from Calico were vetted by none other than Louis Leakey himself. If Jeffrey Goodman is correct, humans might have been at Calico as early as 500,000 years ago.

If there were people here half a million years ago, the Cerutti Mastodon is young like Tupperware. If Hancock is not aware of Calico, he really missed something. If he is aware of it, however, he presumably had some reason for not focusing on it. Perhaps he wasn't convinced by the analysis (does he know more about Paleolithic stone tools than Louis Leakey?) or maybe he was suspicious that the people doing the work misinterpreted the archaeological/geological context of the materials.

I would guess that Hancock has heard of Calico and simply chose not to focus on it (like I said, I don't have the book yet and am just going by the reviews). So . . . he's open to the idea of pre-Clovis (obviously) but doesn't automatically accept all claimed pre-Clovis sites as legitimate, even if competent people were involved?

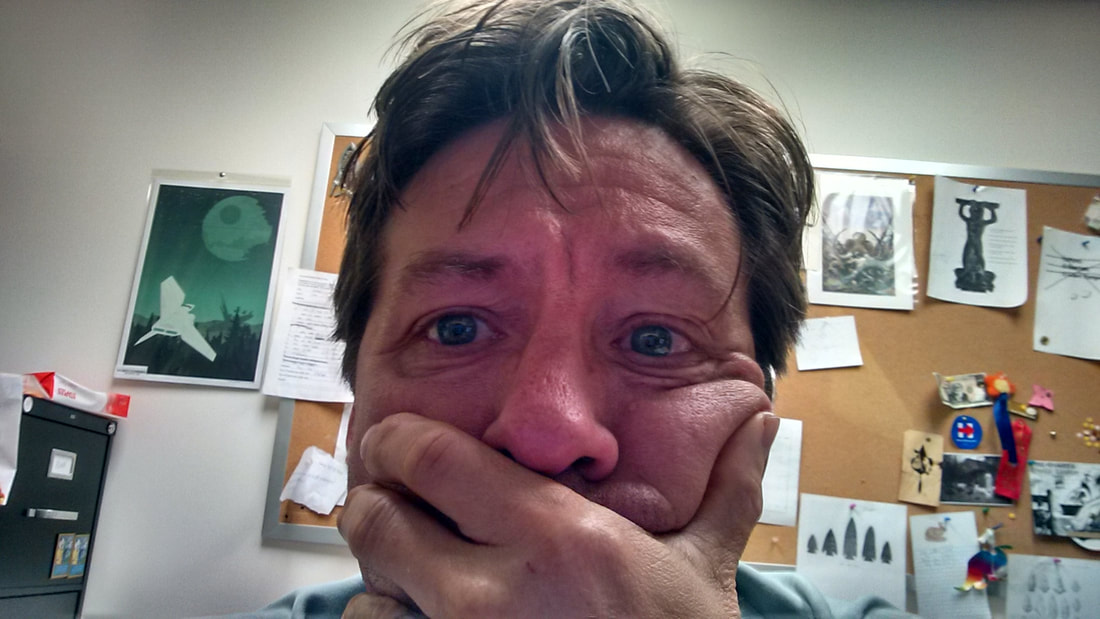

Guess what? That's what all the rest of us do, also. When the Cerutti paper first dropped, my response was not "oh crap, does the dogma say I have to reject this?" (take a drink). No, it was this blog post. I'm just going to quote myself at length:

The 130,000 year-old date is way, way, way out there in terms of the accepted timeline for humans in the Americas. Does that mean the conclusions of the study are wrong? Of course not. And, honestly, I don't even necessarily subscribe to the often-invoked axiom that "extraordinary claims require extraordinary evidence." I think ordinary, sound evidence works just fine most of the time when you're operating within a scientific framework. Small facts can kill mighty theories if you phrase your questions in the right way.

So how should we view claims like this one? For this claim to stand up, two main questions have to withstand scrutiny. First, is the material really that old? Second, is the material really evidence of human behavior?

If we accept the age of the remains, we're left with the second question about whether those remains show convincing evidence of human behavior. As you can see from the abstract, the claim for human activity has several components (modification of the bones, the presence and locations of stone cobbles interpreted as tools, etc.). The authors contention (p. 480) is that

"Multiple bone and molar fragments, which show evidence of percussion, together with the presence of an impact notch, and attached and detached cone flakes support the hypothesis that human-induced hammerstone percussion was responsible for the observed breakage. Alternative hypotheses (carnivoran modification, trampling, weathering and fluvial processes) do not adequately explain the observed evidence (Supplementary Information 4). No Pleistocene carnivoran was capable of breaking fresh proboscidean femora at mid-shaft or producing the wide impact notch. The presence of attached and detached cone flakes is indicative of hammerstone percussion, not carnivoran gnawing (Supplementary Information 4). There is no other type of carnivoran bone modification at the CM site, and nor is there bone modification from trampling."

My impression is that most archaeologists are, like me, skeptical that all other possible explanations for the stone and bone assemblage can be confidently rejected. I'm no expert on paleontology and taphonomy, but as I thought through the suggested scenario, I wondered how all the meat came off the bones before before the purported humans smashed them open with rocks. The authors state that there's no carnivore damage, and unless I missed it I didn't see any discussion of cutmarks left by butchering the carcass with stone tools. So where did the meat go? If it wasn't removed by animals (no carnivore marks) and wasn't removed by humans (no cutmarks) did it just rot away? If so, would the bones have still been "green" for humans to break them open?

The absence of cut marks would be perplexing, as we have direct evidence that hominins have been using sharp stone tools to butcher animals since at least 3.4 million years ago. The 23,000-year-old human occupation of Bluefish Cave in the Yukon is supported by . . . cutmarks. We know that Neandertals and other Middle Pleistocene humans had sophisticated tool kits that were used to cut both animal and plant materials.

Is it possible that pre-Clovis occupations in this continent extend far back into time? Yes, I think it is. Does this paper convince me that humans messed around with a mastodon carcass in California at the end of the Middle Pleistocene? No, it does not.

Words words words. Blah blah blah.

Just.

Produce.

Some.

Evidence.

RSS Feed

RSS Feed