Diehard fans of interpreting the Nevada skulls as Bigfoot crania apparently didn't like my analysis, and one accused me of "not being intellectually honest" because I focused on the misinterpretation of the teeth and avoided "everything else regarding the Humbolt [sic] skull's morphology and ratios, which is what I would have expected an honest, impartial anthropologist to do." In that same exchange, Daniel Dover said "Andy White calls himself a scientist but I'm not impressed with the way he goes off on stuff, making bad assumptions/rants." So there you have it . . . making new friends every day through science! I'm sure neither of these Bigfoot enthusiasts would have had any complaints if I had written a piece declaring that Bigfoot was real.

An aside: I'm not sure why writing a blog post about only one aspect of a skull makes me "intellectually dishonest." By pointing out that the Humboldt skull doesn't have double rows of teeth (which it doesn't) and the Lovelock mandible is not giant-sized (which it's not), did I somehow commit to analyzing every other aspect of those skulls in the same posts? No, I didn't. I mentioned in the Humboldt post that I planned on writing more about the Nevada skulls in the future (and a few days later, voila, I did!). And here I am writing more, which was my original plan. For those of you who want to call me "intellectually dishonest" on some Bigfoot forum that I might never see: if you want to do that (or, perhaps, ask a question or make a point or do something that's actually potentially productive), why not do it on my blog where I'll actually see it? You can even use your same anonymous screen name so your identity will remain a mystery and you can keep your day job without being made fun of for believing in Bigfoot. Try having an honest discussion about evidence. You might like it.

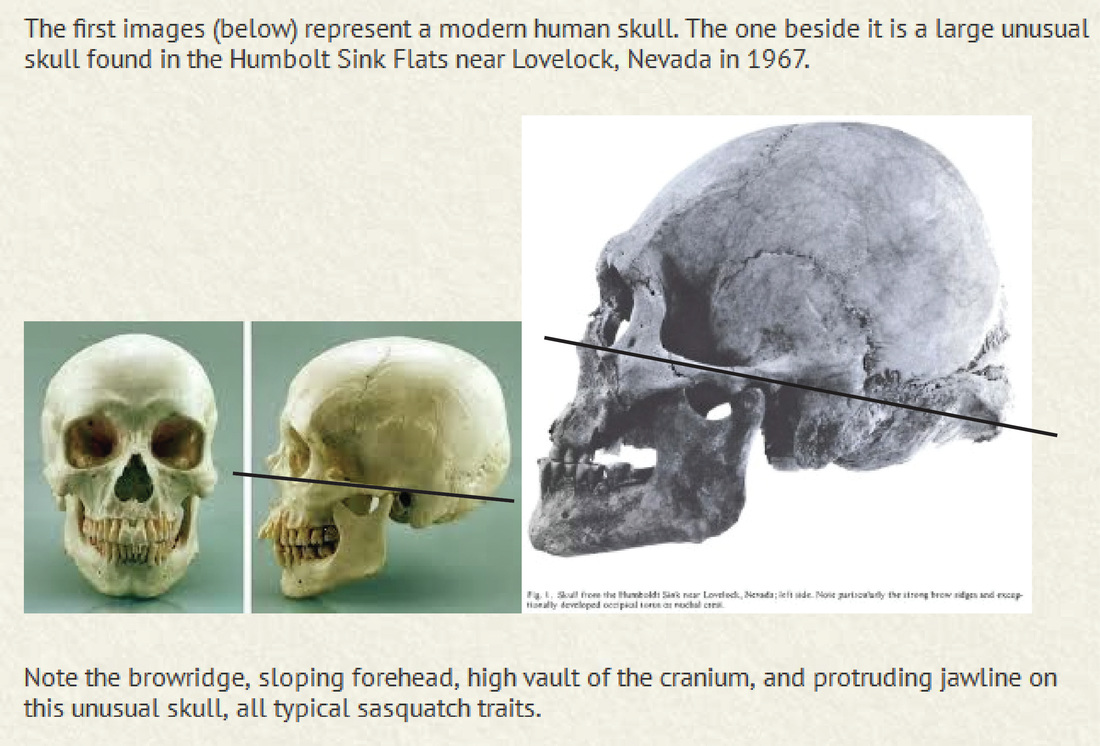

Anyway, let's move on. In this post I'm going to address some of Dover's other claims and interpretations about the Humboldt skull. Dover says that the Humboldt skull has a "browridge, sloping forehead, high vault of the cranium, and protruding jawline . . . all typical sasquatch traits." Here is the image of the skull that he shows, with a "modern human skull" for comparison:

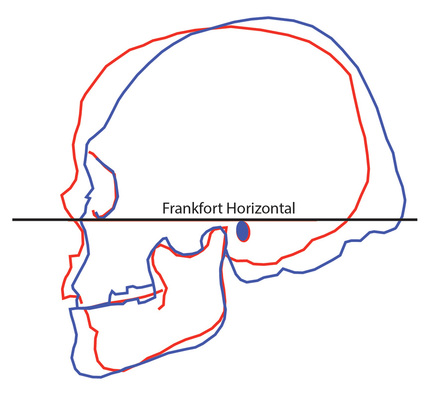

Outlines of the Humboldt skull (blue) and the "modern human" skull (red) that Dover uses for comparison, aligned on the Frankfort horizontal and roughly scaled the same.

Outlines of the Humboldt skull (blue) and the "modern human" skull (red) that Dover uses for comparison, aligned on the Frankfort horizontal and roughly scaled the same. The superimposed outlines show several of the characteristics that Erik Reed noted in his 1967 paper ("An Unusual Human Skull From Near Lovelock Nevada" - I found a copy of it here on M.K. Davis' website): a supraorbital torus (brow ridge), a sloping forehead, and a well-developed nuchal crest. The jaw of the Humboldt skull also appears to project more than the "modern human" skull, as Dover notes.

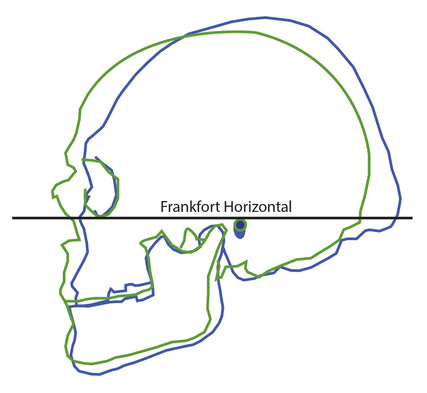

Outlines of the Humboldt skull (blue) and the skull drawing from Gray's Anatomy (green), aligned on the Frankfort horizontal and roughly scaled the same.

Outlines of the Humboldt skull (blue) and the skull drawing from Gray's Anatomy (green), aligned on the Frankfort horizontal and roughly scaled the same. The brow ridge, sloping forehead, and nuchal crest remain, however. Does that mean this is the skull of a Bigfoot and not a Native American? No. That becomes clear if you try to understand what those features actually mean.

There is a lot of variation in human skulls, and there are several overlapping sources of that variation. Some variation can be attributed to sex (male and female skulls have patterned differences). Some variation is geographical (humans in different parts of the world can look different). Some variation is functional (skulls, like other parts of the skeleton, may reflect adaptions for different environments, different degrees of musculature, etc.). Sorting out how much variation there is, what causes that variation, and what that variation might mean (in terms of human evolution, gene flow between populations, movements of populations, patterns of physical activity, etc.) are things that physical anthropologists, paleoanthropologists, and archaeologists wrestle with all the time.

I guarantee you the simplest explanation for the morphology of the Humboldt skull is not that it's not human. The skull is very much human, and the combination of features (brow ridge, sloping forehead, and occipital area with pronounced attachments for the rear neck muscles) that Dover asserts are "unlike what you will ever find on any normal human skull" can be observed on other prehistoric human skulls and in living humans. That doesn't mean the skull is "average" - it is described as a large, strongly constructed skull that falls at the robust end of the modern human spectrum. But it is thoroughly human. Erik Reed (1967) says the following in his description:

"The skull obviously falls--among New World material--in the general category of the archaic type which is most often referred to by Georg Newmann's term 'Otamid variety.' More specifically, it resembles Early period central California material from the lower Sacramento Valley (Newman, 1957) and from Tranquility in the San Joaquin Valley (Angel 1966). Metrical correspondence to the Tranquility crania, as shown in Table 1, is remarkably close. Strong brow ridges, glabellar prominence, and well-developed occipital torus appear in some of the California material.

Finally, the Humboldt Sink skull closely resembles the Ophir calvarium from Virginia City, Nevada (Reichlen and Heizer, 1966)--even sharing the special peculiarity of a genuine os inca."

The Humboldt skull was presumably that of a large male. The brow ridge and sloping forehead are associated mechanically, as the brow ridge serves to reinforce the face against forces generated during mastication when the forehead slopes away rather than being vertical (that's the explanation of the brow ridge that makes the most sense to me, anyway). The biomechanical model of the brow ridge explains why it is so prominent in chimpanzees, gorillas, and many early hominids, and less prominent (to the point of being absent) in many modern humans. The strain placed on the portion of the skull above the eyes increases when the face is more prognathic (i.e., the jaws protrude more), the frontal bone is less vertical, and there is more emphasis on using the front teeth. The brow ridge - the shelf of bone above the eyes - serves to reinforce the face at the point where strain is greatest. Mary Russell wrote extensively about the biomechanics of the brow ridge in primates: here is a paper of hers from 1982; here is a paper of hers in Current Anthropology from 1985 (but most of it is behind a paywall); here is a 1985 commentary on Russell's work by Milford Wolpoff. The take-away point is that the brow ridge likely has a functional (and perhaps even developmental) origin: it's not some random feature that can be used to discern "human" from "nonhuman" skulls. It's easy to find examples of modern humans with brow ridges, especially associated with large, strong males (which the Humbolt skull presumably was). How about Lex Wotton? Nikolai Valuev? Cain Velasquez? Note the brow ridges and sloping foreheads. Last time I checked, none of these guys was a Bigfoot.

There are also biomechanical explanations for the back of the skull. Dover correctly states that the nuchal plane is where the neck muscles attach to the rear of the skull. There is a general relationship between the robusticity of the nuchal crest and the strength of the rear neck muscles - gorillas and chimpanzees have strongly developed nuchal crests because their neck muscles have to hold their heads up while they are moving about as quadrupeds. That doesn't mean that humans can't have big attachments for the nuchal muscles, however, associated with strong muscles at the back of the neck. I wasn't able to find a comprehensive, cross-primate study of the mechanics of the nuchal line/crest while I was writing this post, but that doesn't mean such a study doesn't exist. I would bet there are other examples of human skulls with nuchal crests like those of the Humboldt skull (here is a paper that has a photograph of a Late Pleistocene human from Romania with a moderately well-developed nuchal crest; here is Angel's 1966 paper on the skeletons from Tranquility, CA, that is mentioned by Reed). Dover's statement that "Human skulls have no such markedly protruding nuchal crest" like that of the Humboldt skull is an assertion that I would guess won't stand up to scrutiny. There's no doubt the Humboldt skull has a big nuchal crest, but that doesn't mean there's nothing else like it in the world and that the skull is therefore not human.

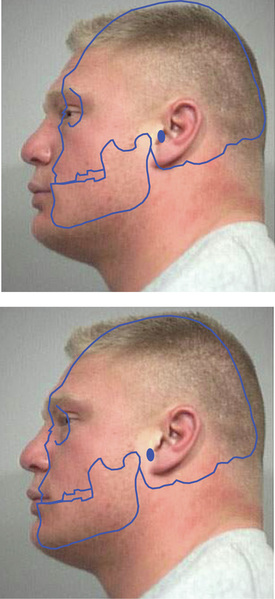

In the bottom illustration, I have placed the Humboldt outline so that it corresponds pretty closely to Lesnar's profile. This puts the orbit a little too far forward and the external auditory meatus a little low, but you get the idea: the shape of the Humboldt skull, presumably that of a large, powerful male, is not inconsistent with the shape of the skull of another large, powerful male. I have no idea what Brock Lesnar's occipital area looks like, but it wouldn't surprise me if his skull had a nuchal crest just as pronounced as that of the Humboldt skull. If you think this makes Lesnar a Bigfoot, I'll let you be the one to tell him that.

The Humboldt skull is the the skull of a human, not a Bigfoot. All the features found on the skull are found in humans. The impression that the jaw of the Humboldt skull juts out significantly farther than a jaws of "modern humans" is incorrect, as shown by the comparison (in proper orientation) with an average human skull. The remaining combination of features that Bigfoot enthusiasts seem to be homing in on as "nonhuman" - the brow ridge, the sloping forehead, and the well-developed nuchal area - are characteristics that are most often expressed in humans that are large, powerful males. I would guess that's what the Humboldt skull is - the remains of a large, powerful male.

A Native American male, not a Bigfoot male.

References:

Reed, Erik K.. 1967. An Unusual Human Skull from Near Lovelock, Nevada. Miscellaneous Paper 10, University of Utah Department of Anthropology, Anthropological Papers. Salt Lake City: University of Utah Press.

RSS Feed

RSS Feed