"Townsend’s information will be published in a research paper, and he challenges the scientific community to discredit his information. He said the four-year project helped solve the mystery because the focus was based on forensic evidence. The information used was also heavily based on comparison proof from the top scientists in the world."

I was intrigued, so I waded through it.

The paper describes three "bone stacks" located and documented by the authors in the Mt. St. Helens area in 2013 and 2014. The authors attribute the formation of these bone assemblages to Bigfoot, arguing that (1) the stacks of bones could not have been created by any other known carnivore in the area and (2) the bones preserve evidence of consumption by a creature with very large but very human-like teeth. Here is a quote from Townsend's "discovery narrative" about the first bone stack (pg. 6):

Townsend later (pg. 7) reiterates his vision of the behavior that created the record he was looking at:

"What resident animal species would kill deer with blunt force trauma on the head, position them in the same directional orientation, eat the animals and drop the bones in a pile? How come scavengers were avoiding this site even though some of the bones still had flesh attached? These were just some of the questions now rushing through my thoughts."

- Bone Stack #1 (BP1): 4 ribs, 8 lower foot bones, 2 wrist/ankle bones, a toe bone, and 2 partial hooves from black tail deer (a "partial shoulder assembly" was observed but not collected, and two damaged skulls were present);

- Bone Stack #2 (EK#1): 4 ribs, 1 vertebra, and 4 lower leg bones from an elk. (in the discovery narrative, the authors report that the skull was also observed in the general area but "The odd thing was we found no leg bones in the area, as if they had been carried off later");

- Bone Stack #3 (EK#2): "The lower spinal column, some ribs, and one rear leg were located in this location among elk hair tufts" (pg. 30).

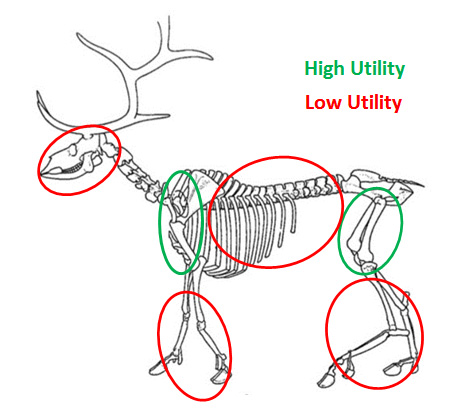

Students of anthropological archaeology will have anticipated where I'm going with this based on the title of the post: the bone stacks described by the authors appear to be examples of "low utility" assemblages, composed of the skeletal remains of those parts of the animals that contain relatively little meat. All hunters know that different parts of a large animal have different "values" in terms of their protein and fat content. For cervids like deer and elk, the highest utility parts of the animal (those with the greatest concentration of edible tissue relative to bone) are the upper limbs. Heads, feet, lower limbs, ribs, and the spine -- the kinds of bones described in the bone stacks -- contain relatively less meat per unit of volume (and hence per weight). When hunter-gatherers on foot (i.e., lacking ATVs, snowmobiles, pick-up trucks, and other mechanized transport technologies utilized by many sport hunters) must choose which parts of the animal to transport back to camp after a kill, they generally (and logically) pick the highest-utility pieces. As a general theoretical expectation, they will butcher the animal and preferentially transport the upper limbs back to camp, leaving behind the feet, heads, spine, etc. Thus we can generally expect that kill/butchery sites will have high proportions of low-utility parts while the camp/consumption sites will have high proportions of high-utility parts.

Binford's contribution was the beginning rather than the end of the "hunting-scavenging debate," which continues to this day (e.g., here is an open access paper from 2013). It has been incredibly productive in terms of the development of new theory and new lines of evidence, and is one of the best examples of the inductive-deductive cycles that I know of in archaeological science. Without writing a book about the twists and turns of the history of the debate and where it is now (which I would not be qualified to do), I will just say that it appears to me as though an early human hunting model fits better with the multiple lines of direct and indirect evidence we have in front of us now than does a passive scavenging model. Not everyone will agree with that statement, of course.

But getting back to "Bigfoot:" what could the composition of the head-foot-rib-spine-dominated assemblages of the bone stacks be telling us about the behaviors that produced those assemblages? The absence of the high-utility parts suggests to me that someone or some thing carried off the parts that had the most meat on them. I don't know much about what bears or cougars do to a dead deer, but I doubt they selectively dismember it and carry off just the good parts. That sounds like human behavior to me. Townsend's vision of Bigfoot sitting on a tree branch and munching on the ends of (low utility) ribs at the kill site doesn't make a lot of intuitive sense if the (high utility) limbs were the prize of the kill. Would Bigfoot enthusiasts who accept this evidence argue that the creatures are employing essentially human foraging strategies, selectively transporting portions of their kills back to a home base to share with friends and relatives? And if groups of Bigfoot are hunting separately but then bringing portions of their kills back to some central place to share (as would be implied by the removal of the high utility parts), where are the dense concentrations of bones that those behaviors would produce? Generally, those kinds of re-occupied, re-used sites "central place" sites are much easier to spot than kill sites that are produced, used, and abandoned over very short periods of time. If we can find these "central place" kinds of sites in Africa from 1.8 million years ago, how come we don't know about any in the Cascade Mountains? Three kill sites with no high utility bones but no sites where the "good parts" are consumed? Is Bigfoot really that tidy?

What about the stacking behavior? The authors (pg. 67) quote a Washington State Department of Fish and Wildlife bear and cougar specialist (Richard Beausoleil) as saying the following:

“To me, the bones look like they were placed there by a human (hunt site, illegal bait site). You looked at a lot of species to explain this, but in my experience with carnivores, this one is likely tied to Homo sapiens”.

And what of the reported tooth marks? This is a part of the report I have not yet considered in detail. I would be surprised to find that the tooth marks could not be reasonably attributed to non-human carnivores (perhaps more than one kind). But I'll reserve comment on that until I read through their analysis carefully.

In summary, we're told that the bone stacks are the results of single events: a Bigfoot killing a deer (or two), sitting down and depositing ribs in a pile, one after the other as he/she eats. But it's easy to imagine an alternative hypothesis (the selective use of leftover, low utility parts in bait piles for illegal hunting) that also appears to account for many of the facts presented by the authors. If those alternative hypotheses were fleshed out, it would be possible to develop critical test expectations that could falsify one or the other. I don't think we're given enough information to judge where in the sequence of butchery and deposition the bones were chewed -- before being "stacked"? after? Did the biting occur around the time of death or later? Are there any cutmarks on any of the bones that demonstrate that tools were used to disarticulate the carcasses? Are there bite marks on any bones that are not in the "stack"? As shown by the "discovery narrative" I quoted above, the assumption that the killing, biting, and stacking all happened at about the same time seems to have been embedded in Townsend's thinking about these sites since the moment of discovery. Discarding that assumption and considering the formation of the sites as a set of analytical questions (which, admittedly, it may not be possible to address satisfactorily with the information they report) may result in a simpler answer than "Bigfoot."

I'm curious as to why the Bigfoot community did not seem to get excited about this work. Anyone care to chime in?

RSS Feed

RSS Feed