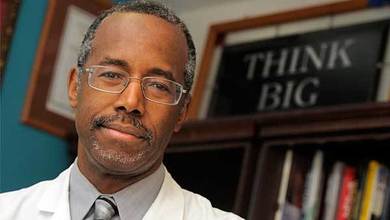

Ben Carson: thinking big . . . but how big? (Image source: http://www.wnd.com/2014/11/1393785/)

Ben Carson: thinking big . . . but how big? (Image source: http://www.wnd.com/2014/11/1393785/) That's my hypothesis, anyway, and I think it's a pretty strong one. I'll explain how I developed it in a moment. First, I'd like to explain (to Carson and anyone else who might not get it) what science is and how it works. It became apparent to me while watching Carson speak that he either really doesn't get it or he really does but just doesn't want you to get it. It's hard to imagine as president a neurosurgeon that doesn't understand what science is, but we twice elected a Yale graduate who couldn't pronounce "nuclear" correctly, so anything's possible. If you already know how science works (and why archaeology and paleoanthropology are sciences), skip down a few paragraphs.

Science is the systematic study of the natural world. That's a broad definition. It has to be, because exactly how you do science depends on what you're studying. You can't really study distant stars, for example, in exactly the same way you study cancer cells. You can't study radioactive isotopes in the same way you study human geopolitics.

But different things can all be systematically studied in ways that harness the power of scientific inquiry to build on itself. Astronomers, biologists, chemists, and political scientists can all do the same thing at a general level: use evidence to evaluate competing ideas about the world and make a determination of which of those ideas is more plausible, more credible, and more likely to be true. In a classic scientific framework, this is done by formulating hypotheses and testing them to see if they can be falsified. The winnowing out of incorrect ideas is what allows science to be cumulative.

Archaeology, paleoanthropology, geology, and paleontology are sciences that deal with trying to understand what happened in the past. These are challenging fields of study because of our inability to directly observe the phenomena we're ultimately interested in. As George W. Bush famously said: "I think we can all agree the past is over." You can't turn back the clock, alter a variable, and re-run the system to see what the outcome is. That's very different than what happens routinely in sciences like physics and chemistry where you can use controlled experiments to evaluate your understanding of cause and effect, your explanation of a phenomenon, or your ideas about the nature of the relationships among variables.

The fundamental inability to observe what we're studying makes archaeology, by necessity, a theoretical science. No, "theoretical" is not a bad word. No, it doesn't mean that archaeology is "just a guess" or that archaeologists have no way of knowing if they're right or wrong. It means that archaeologists develop theory (ideas about why things are the way they are) and models (descriptions of how variables fit together). From that theoretical framework, we derive expectations that we can compare to archaeological data (which generally consists of material remains of human cultural behavior). If our archaeological data contradict our theoretically-derived expectations, then something about our theoretical framework is wrong (assuming the data are correct). Then it's back to the drawing board to adjust the theoretical framework to account for the data. Then we can derive new expectations and attempt to test them. Once we're in that inductive-deductive loop of falsification, we're doing science. Outside of that loop, we're not. Ideas that are impossible to falsify just aren't that useful. A crazy, unfalsifiable idea could actually be true, of course, but we can't ever know because there's no way to test it. We have to have some way to know if we're right or wrong about something.

On it's good days, paleoanthropology -- the study of the human past through fossils -- is also a theoretical science. Paleoanthropology is tightly entwined with the theory of evolution by natural selection, which provides it with a theoretical description of the processes and mechanisms of evolutionary change. Fossils and other sources of data (including archaeological data and, increasingly, genetic data derived from fossils) provide the direct evidence that can be compared to our ideas about the past. Paleoanthropology is just as much a science as astronomy, biology, chemistry, and physics.

Which brings us to Ben Carson, finally, and my hypothesis that he believes in giants.

This morning I watched Carson discuss his views on creation and evolution in this 2011 presentation. It's no secret that Carson is a creationist. His trademark soft-spoken, humorous approach to connecting with audiences is on full display as he spends 45 minutes glibly reciting Creationism 101's greatest hits to the friendly crowd, weaving in anecdotes designed to convey how great of a surgeon he is and how dumb all the "evolutionists" are. Most of his points regurgitate the same silly nonsense we've heard before: "life is too complicated to have been an accident;" "where are the transitional fossils?;" "how did the eye evolve?;" "a global Flood explains the Earth's geology;" etc. It's painfully apparent that he either misunderstands or is willing to misrepresent evolution, evolutionary theory, and fossil evidence (in fact he actually says that Darwinian evolution comes from the Devil). Twice he poses the profound question (and I'm paraphrasing here): "If evolution is so efficient, how come we don't just split apart like amoebas to reproduce?"

Dr. Carson, you have clearly demonstrated that someone in the creation-evolution debate is dumb, but I'm guessing we'll have to agree to disagree about who exactly that is.

Except for his explicit statement (around 19:40) that he doesn't believe the Earth is only 6000 years old, much of what Carson said reminded me a lot of the talking points I had recently heard in an interview of Young Earth Creationist and convicted criminal Ken Hovind. Particularly striking was that Carson, like Hovind, used the word "degenerated" when talking about the human present as compared to the human past (starting about 28:35):

"Do you know, your brain -- and this is a conservative estimate -- could take in one new fact every second for over three million years before you'd begin to challenge its capacity? . . . And that's our brains in their degenerated state. Can you imagine what they were like before?"

As I discussed in my post about Hovind, the "degeneration doctrine" is the idea that the clock has been running down since creation, resulting in humans and animals that are smaller, simpler, and farther from how they were created (i.e., as perfect). Compare Carson's statement to Hovind's:

"But he was probably off the charts IQ compared to us today. So Man started off smart, and we're getting smaller, dumber, and weaker as time goes by, I believe."

The degeneracy doctrine is an extra-biblical idea (where does it say in the Bible that Adam was really tall? Or really smart? Or had better DNA?) that is connected to creationist belief in giants. Based on a complete misunderstanding or misrepresentation of what the theory of evolution actually is, creationists like Hovind suppose that demonstrating the existence of giants would simultaneously prove biblical creation to be true and the theory of evolution to be false. That's why they're so interested in finding giant human bones: they really want to show them to the world as evidence. But so far they have been able to produce none (the lack of actual bones led Joe Taylor to produce and sell a sculpture of a 47" femur). The complete lack of positive evidence is a real bummer for giant enthusiasts of all stripes.

I think Carson believes in giants because he subscribes to the degeneracy doctrine. His use of the term "degenerated" is, I think, evidence that the idea of "devolution" is submerged somewhere in this thinking. If so, it is logical to presume that he believes human used to be taller in the early years following creation. I would also guess that Carson's biblical literalism would lead him to interpret Genesis 6:4 ("There were giants in the earth in those days") as consistent with that.

This hypothesis is easy enough to falsify: someone just needs to ask Ben Carson if he believes in giants. The answer will be interesting either way, won't it?

According to recent polls, Carson and Donald Trump are leading the pack to be the current nominee. A recent tiff over who has faith and who doesn't comes as the pair begins to court Evangelical voters in Iowa, where the first primary will be held. I think the "do you believe in giants?" question would be an excellent one to ask at the debate in California this Wednesday. Do we want a president who believes in giants? Or, alternatively, can we afford to have one that doesn't?

I'm an archaeologist. I am trained to observe patterns, create a model that explains those patterns, and attempt to test that model by developing expectations that can be compared to empirical data.

Ben Carson believes in giants. That's my hypothesis. I have surmised the existence of a degeneracy doctrine that is a component of Young Earth Creationism and I have associated that doctrine with a belief in giants and a misunderstanding of evolution (and science in general).

What do you say Dr. Carson? Do you believe in giants?

RSS Feed

RSS Feed