If I'm part of a conspiracy, I have yet to be told about it. Maybe someday "they" will let me in on the secret and I can start writing blog posts on a laptop with a fully functional keyboard and a working battery, maybe even while not at home watching kids on evenings and weekends. Just think how effective I could be if I could work without also being responsible for wiping noses, stopping couch wrestling, and pretending to eat imaginary pasta.

The fact is, professionals get things wrong also. Today's "whoops" comes from Paolo Viscardi, a natural history curator at the Grant Museum of Zoology in London. This "Ask a Biologist" page includes Viscardi's answer to the question "Were there ever giant humans?, which includes the following:

"Next I would say that there were Pleistocene apes called Gigantopithecus that stood about 10 feet tall. Their remains are very similar to those of humans, particularly when the skull is damaged. Mammoth and elephant skulls are also remarkably humanoid in appearance when they are damaged."

The appeal to the remains of Gigantopithecus is as unfortunate as it is wrong.

While there was a genus of ape (that we call Gigantopithecus) that existed in South and East Asia during the Pleistocene, we only know of these creatures through a few mandibles and teeth. No-one has ever found a Gigantipthecus skull or any other part of the skeleton. Just teeth and mandibles. So how could we say the remains of a Gigantopithecus look like those of a giant human? We can't, because we've never seen them.

The teeth and mandibles of Gigantopithecus are large. Those teeth and mandibles form the sole basis of our estimates of body size. Big teeth and jaws mean a big primate, right? Well, sort of. The problem is that there is a lot of variation among primates in the relationship between tooth size and body size (I touched on this subject in this post about why the original owner of the large Denisovan tooth wasn't necessarily a giant). Tooth size alone doesn't necessarily tell us much because tooth size is related to diet. Relatively small-bodied australopithecines had large grinding teeth because they had a diet that included a lot of tough, low quality foods that needed to be heavily masticated. The teeth and jaws of robust australopithecines (which were also small-bodied compared to modern humans) were even larger and were accompanied by a skull and chewing muscles that were clearly designed to produce and resist massive chewing forces.

Liuzhou, China: fossils of Gigantopithecus waiting to be discovered?

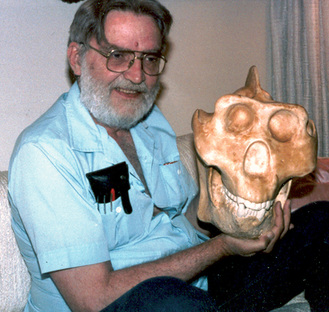

Liuzhou, China: fossils of Gigantopithecus waiting to be discovered?  Grover Krantz and his reconstruction of the skull of Gigantopithecus.

Grover Krantz and his reconstruction of the skull of Gigantopithecus. "Meldrum borrowed from the physical looks of extinct animals such as the Gigantopithecus blacki — an ancient ape that was twice the size of apes today — and the Neanderthal — a species of human that is said to have became extinct 40,000 years ago."

So this "Bigfoot skeleton" is based partially on the "looks of extinct animals such as the Gigantopithethecus blacki"? Oh my. If you've read this far, you know that we really don't know much about what those extinct animals actually did look like. We've got some teeth and mandibles - that's it. From those meager remains, wishful thinkers (including academics) have built up several real-looking reconstructions that will probably be cited for years to come as actual evidence. That's why Viscardi's statement ("Their remains are very similar to those of humans, particularly when the skull is damaged") is so unfortunate: he's reinforcing the incorrect notion that all of this business about the giant, bipedal Gigantopithecus is fact, established based on the existence of skeletons and skulls.

That's just not true.

Maybe Gigantopithecus was a 10' tall biped. But maybe it wasn't. What we don't know about Gigantopithecus far outweighs what we do know. That vacuum of knowledge is what allows all kinds of notions (not all of which can be correct) to survive. Some of those notions will be killed off when actual postcranial remains are found. In the meantime, I hope that academics will take care to convey to the public what we actually do and do not know about this creature.

RSS Feed

RSS Feed