The bad ones irk me. If we're concerned about what the public knows about archaeology (we should be) then we should care when popular articles get things wrong. The large majority of the audience for these pieces is never going to go and read the original paper that an article is based on: in many cases they won't be able to because the peer-reviewed publication is behind a paywall. What's in the article is what they can take away.

Over the last few days, this University of Michigan press release about an Early Paleoindian site in southern Michigan has been emailed to me and has popped up in regional Facebook groups of which I'm a member. It describes recent work at the Belson site. The site and the work there are interesting. But the article is not good.

The headline waves the first red flag:

"Farm field find rewrites archaeological history in Michigan"

Here's a tip for aspiring writers of archaeological content for popular consumption: stop saying things like that. It's like using ALL BOLD CAPS to announce that the time of Wednesday's school board meeting has been changed from 5:30 to 6:00. Reserve "rewriting history" for something really big. Also: stop saying scientists are "baffled" or "left speechless" by things we "can't explain." Trust me -- we're never speechless. Even when we can't explain something we'll still talk about it. Probably even more than when we can explain it.

"Thirteen thousand years ago, most of Michigan was covered in a wall of ice up to a mile high."

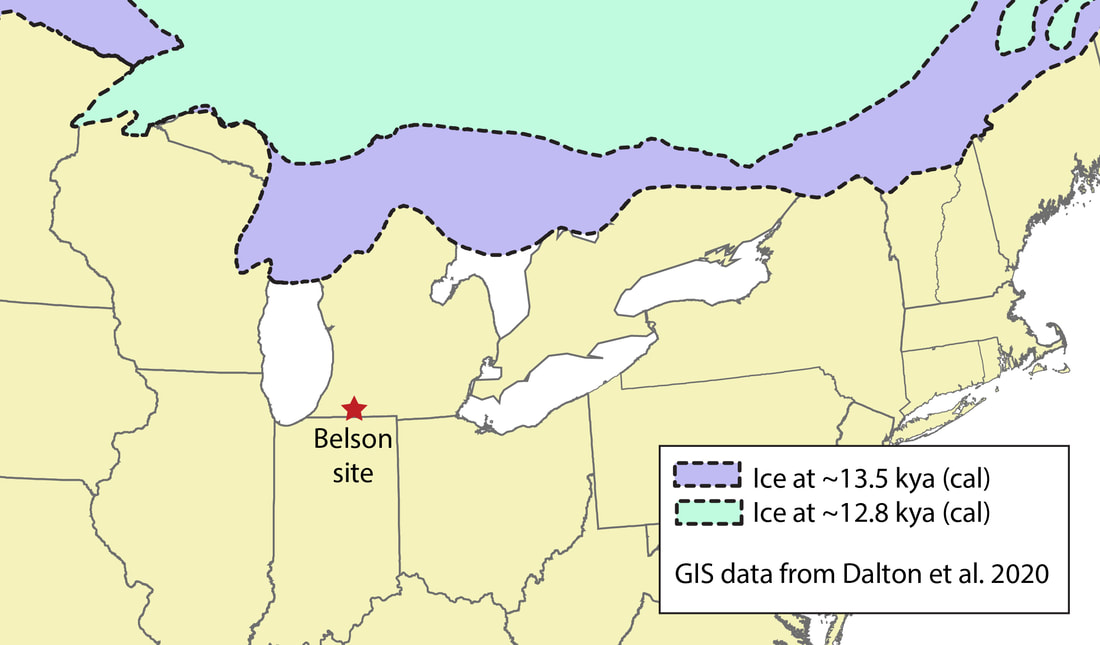

That is incorrect. The glacial ice may have been that thick at the height of the last glaciation (perhaps 26,000-20,000 years ago), but by 13,000 years ago the ice front was retreating from Michigan's upper peninsula. Most of the lower peninsula was probably ice free by about 15,500 years ago. The ice sheet position data I used to make the illustration below come from a 2020 paper by April Dalton and colleagues.

This is the second sentence:

"Archaeologists believed this kept some of the continent’s earliest people, a group called Clovis after their distinctive spear points, from settling in the region."

No, archaeologist don't and didn't believe that a wall of ice kept Clovis peoples out of Michigan. This isn't Game of Thrones.

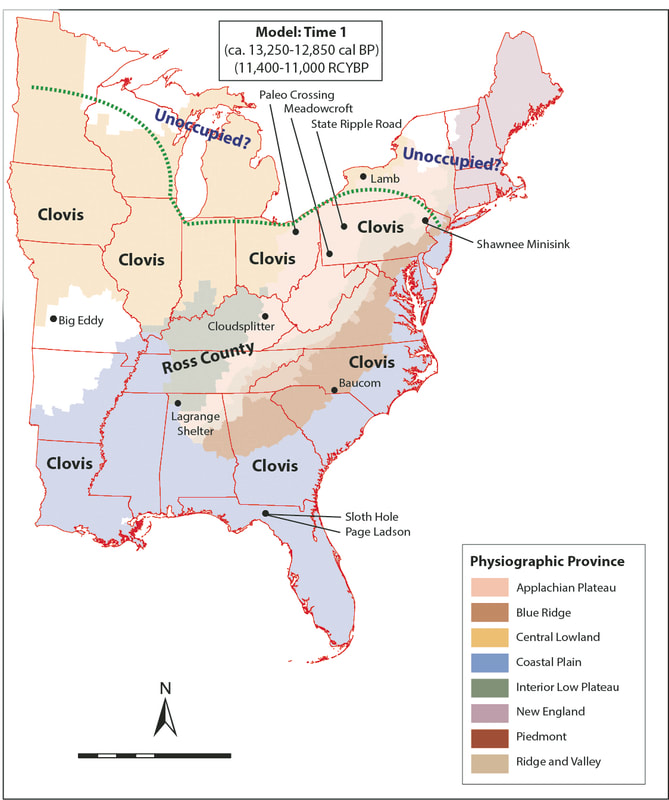

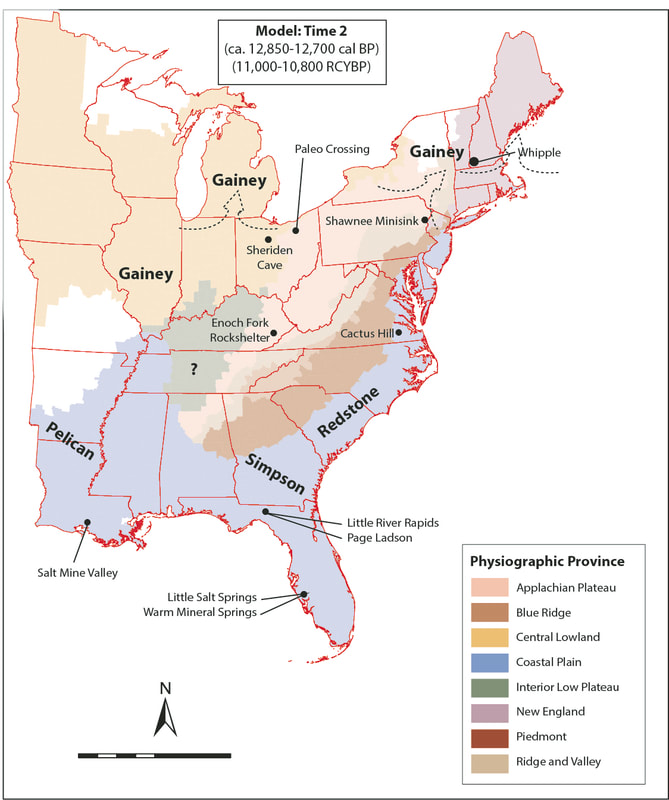

The lack of a classic Clovis presence in the region is attributed, rather, to the notion that the environments of the area were still maturing following the retreat of the glacial ice. The idea is that it would have taken some time for the stable ecosystems that are attractive to hunter-gatherers to develop after the ice was gone. We have plenty of evidence in lower Michigan of Early Paleoindian peoples using fluted points that we call "Gainey." These points are very similar to Clovis, but with some key manufacturing differences that many of us (myself included) think are probably related to time. The presence of these "slightly later than Clovis" points and the absence of true Clovis points suggested that the first movements of human populations into Michigan may have been post-Clovis in age (but not by much).

The two maps below are from a 2017 presentation that I gave (co-authored with David Anderson) about demographic shifts in Paleoindian populations. They illustrate our understanding of the northern limits of Clovis and the idea that Gainey represents a demographic push of people into the central part of lower Michigan.

And then we get to the third and fourth sentences:

"But an independent researcher along with University of Michigan researchers have identified a 13,000-year-old Clovis camp site, now thought to be the earliest archaeological site in Michigan. The site predates previously identified human settlements in the Michigan basin and potentially rewrites the history of the peopling—or settling—of the Great Lakes region."

Early? Yes. Earliest? Probably not. There is some evidence already for human use of the area during Clovis and pre-Clovis times in the form of mastodon remains that Dan Fisher (also of the University of Michigan) argues were butchered by humans. This evidence is discussed in the professional paper published in PaleoAmerica, as is another possible Clovis site (the Palmer site) documented in southeast Michigan. The published paper is behind a paywall, unfortunately, but there is a copy on Brendan Nash's Academia.edu page. The author of the press release surely would have had access to a copy of the paper.

The story improves from there, likely because it largely depends on quotes from the researchers. One odd thing is Nash's statement about "early humans" having a "wolf model of subsistence" and "running other ice age predators such as saber-toothed tigers and short-faced bears off their prey." I'm honestly not sure if this is supposed to refer to Early Paleoindians or some other people at some other time in some other place. It's possible the quote was garbled. I do know that there really is no consensus about Early Paleoindian subsistence practices - what they ate and how they got it has been the subject of lively debate for decades. I don't recall ever hearing of the "wolf model of subsistence."

The popular article about work at the Belson site has gotten a lot of attention. The site is interesting, and the professional publication clearly shows that is has the potential to add to and alter our conceptions of the earliest peoples in Michigan. It's too bad the opening of the popular piece wouldn't pass muster at a fifth grade science fair. I'm a little surprised that the University of Michigan would put its stamp on something that frames the work of its researchers in this way. We need these kinds of articles to communicate our work to the public. But we also need them to be accurate. I hope that we can do better.

RSS Feed

RSS Feed