I'll write more about the field school as it moves forward. I'm considering including a small online writing requirement in the syllabus, as communicating with the public about archaeology is important both for the education of the students and for our discipline as a whole. I'll keep you posted. In the mean time, enjoy this picture of the Broad River on a crisp fall day (taken last week during a visit to the site).

|

This is just a quick update on the spring archaeological field school I announced in November. I'm happy to report two things: (1) the class has filled up; and (2) I have received notice that my request for financial support from the Archaeological Research Trust (ART) has been granted. ART grant monies will support wages for a field assistant, wages for a lab worker to keep up with processing artifacts, samples, and paperwork as we produce it in the field, and purchase of expendable field supplies and materials to stabilize the site. Thank you, ART members and board: you won't be disappointed!

I'll write more about the field school as it moves forward. I'm considering including a small online writing requirement in the syllabus, as communicating with the public about archaeology is important both for the education of the students and for our discipline as a whole. I'll keep you posted. In the mean time, enjoy this picture of the Broad River on a crisp fall day (taken last week during a visit to the site).

2 Comments

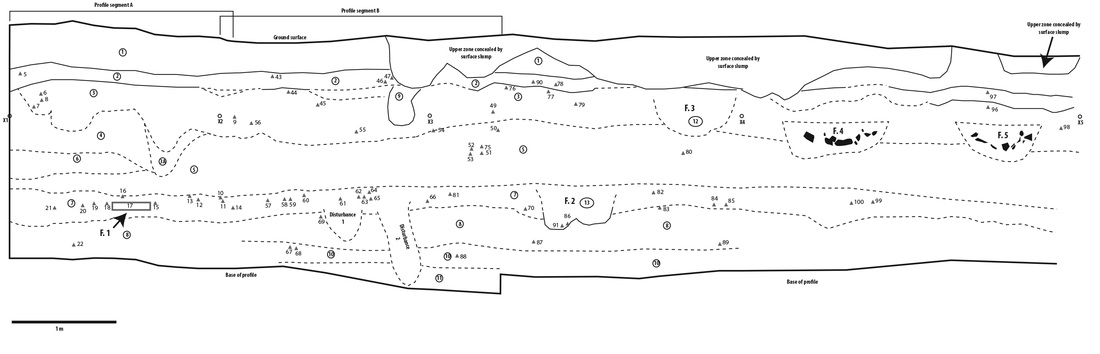

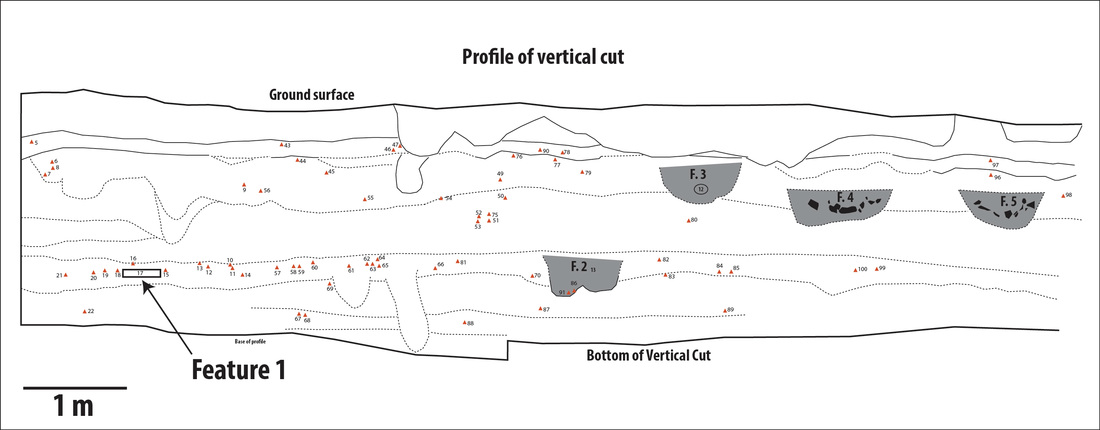

What has been learned about the site so far has come through some very preliminary fieldwork. In the fall of 2015, archaeological materials were discovered eroding out of a 2.4 m (~8’) high, 10 m (~33’) long vertical exposure that had been created by the removal of fill dirt from a small portion of a natural levee. Cleaning and documentation of the profile revealed stratified, well-preserved cultural deposits including ceramic-bearing strata near the surface, pit features at various depths, and a horizontal zone of quartz chipping debris buried about 2 m (6.5’) beneath the surface. Artifacts show that the levee was used as a camp site over a span of at least 5000 years. At least some of the chipping debris (shown as Feature 1 in the profile drawing) can be fitted back together, suggesting that the deposit was created when prehistoric peoples sat at that spot to make stone tools. The deposit is thought to be Middle Archaic in age (dating to perhaps 4000-3000 BC) because of a quartz Guilford point that was recovered from the slump at the base of the profile. The goals of the excavations will be to: (1) continue straightening, documenting, and stabilizing the exposed vertical wall; (2) collect controlled samples of artifacts that can be used to understand the 5000-year-long occupational sequence of the levee; and (2) expose discrete cultural deposits so that they can be mapped and excavated.

Hand excavation will be used to straighten and plumb the vertical cut, exposing a long profile that will be documented during the field school. Dr. Christopher Moore (SCIAA) will assist in interpreting the exposed natural and cultural deposits. After exposure, straightened sections of the wall will be protected from further damage using landscape fabric and wooden buttressing. Hand excavation blocks will be opened in two areas. One 3 m x 2 m excavation block will be placed on top of the levee a safe distance from the existing vertical exposure. Excavations will proceed in 10 cm levels in 1 m x 1 m units, screening all sediments and creating plan maps at the base of each level. Discrete deposits (such as hearth features, storage pits, postholes, or in situ deposits of chipping debris) will be documented and excavated. A 2 m x 2 m excavation block will be opened near the base of the existing vertical exposure, enlarged as needed for safety. The purpose of this excavation area will be to extend the profile vertically downward and explore any cultural deposits present beneath the presumed Middle Archaic zone. Enrollment is capped at 12. This should be a lot of fun. It's a great spot for a field school: it's close, it's known to contain complex and interesting archaeological deposits, and it's cared for by a very supportive landowner. If you're a student interested in taking this course, please email me with any questions: aawhite@mailbox.sc.edu. Stay tuned! I've loaded a pdf version of my 2016 SEAC presentation "Social Implications of Large-Scale Demographic Change During the Early Archaic Period in the Southeast" onto my Academia.edu page (you can also access a copy here). Other than a few minor alterations to complete the citations and adjust the slides to get rid of the animations, it's what I presented at the meetings last Friday. I tend to use slides as prompts for speaking, so some of the information that I tried to convey isn't directly represented on the slides. There's enough there that you can get a pretty good idea, I hope, of what I was going for.

I tend to be an introvert, which is one reason why it recharges me to spend time in my garage with just my scrap metal pile, the radio, and the rats. For me, conferences are a strange mix of intellectually stimulating and physiologically draining. I had to tap out of SEAC early Saturday afternoon: two and a half days of listening, thinking, talking, and interacting had worn me out. Conference fatigue is one sign that you're doing it right. Another is leaving with more excitement and ideas than you walked in with. I can't speak for anyone else's experience, of course, but I saw some really interesting papers and talked to a lot of interesting people. A lot of the questions I'm interested in require information from a lot of different areas across large time spans, so I'm still in the process of working my way up the proficiency slope of Southeastern archaeology and learning as much as I can as quickly as I can. I apologize if I met you and you felt interrogated. One of the major things I took home from this conference was that there has been an important broadening of enthusiasm for subjects that used to be considered bizarre, baseless, unscientific, and even too political for archaeology. I got the impression that talking about ritual, symbolism, and belief systems (hot topics for decades among those who focus on the materially-rich Middle Woodland and Mississippian "florescences" of the Eastern Woodlands) is now also quite common among those who work on the Paleoindian and Archaic periods. I saw numerous papers asking new questions about material remains, and they were fascinating.

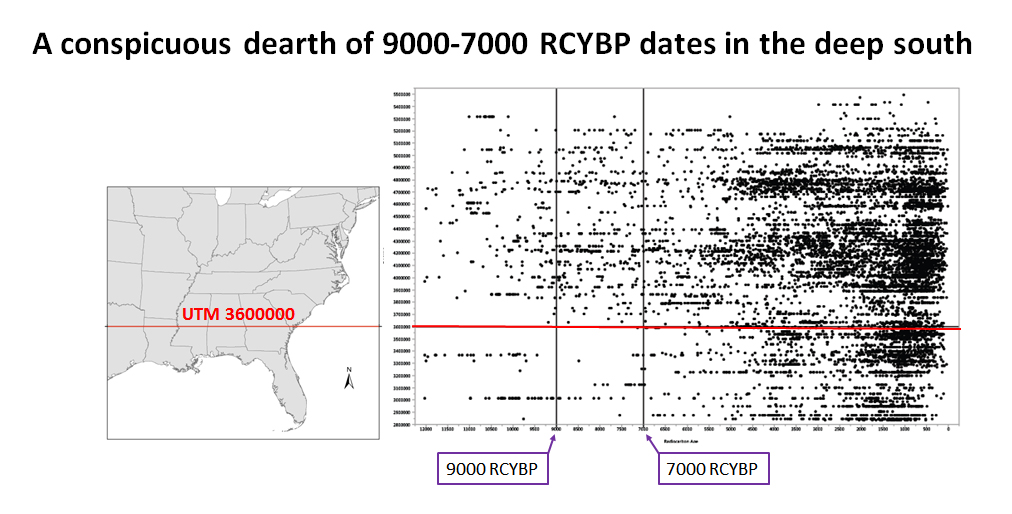

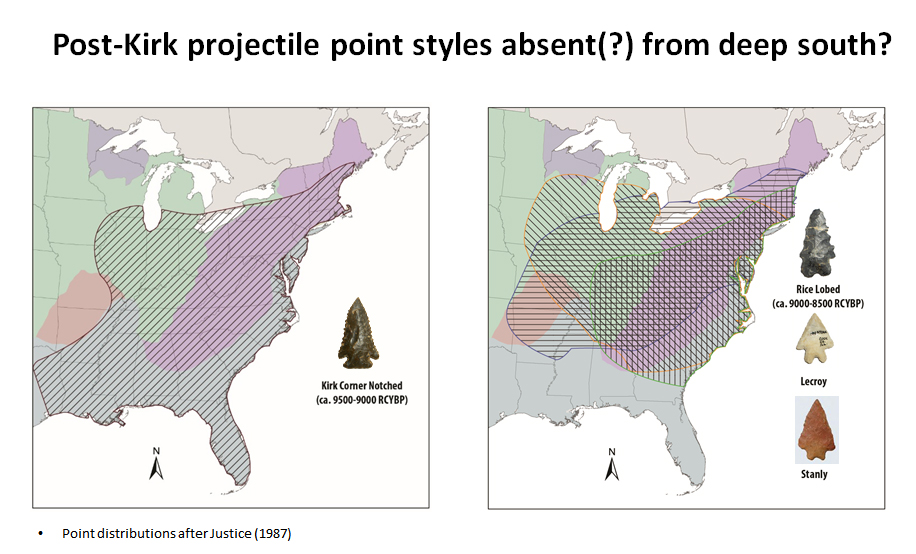

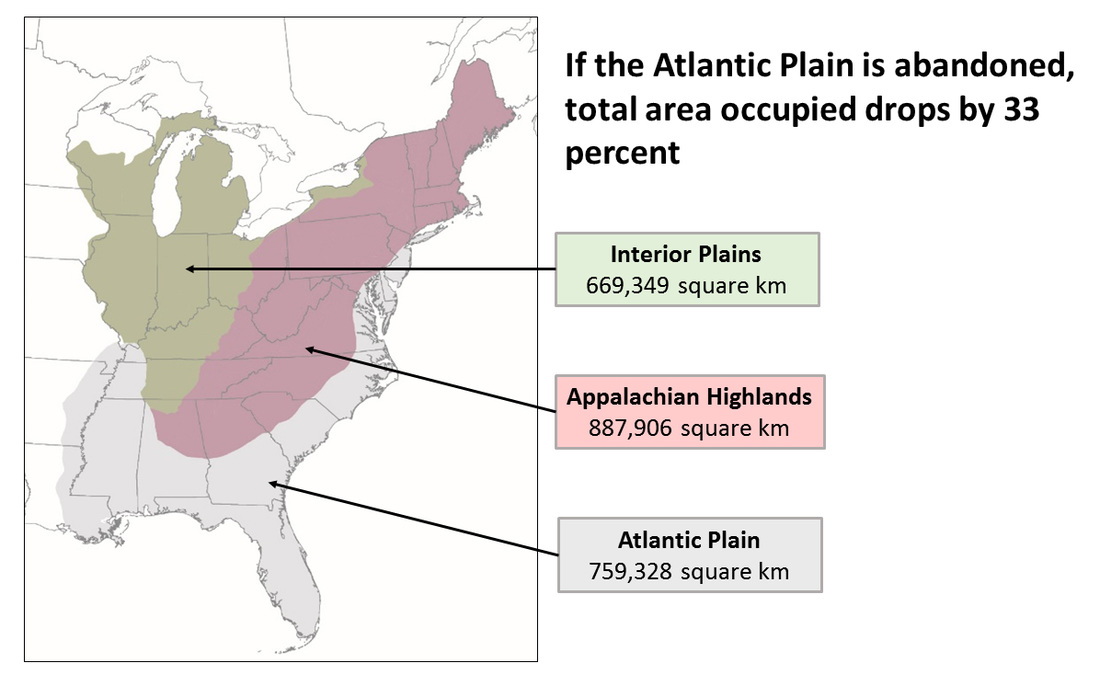

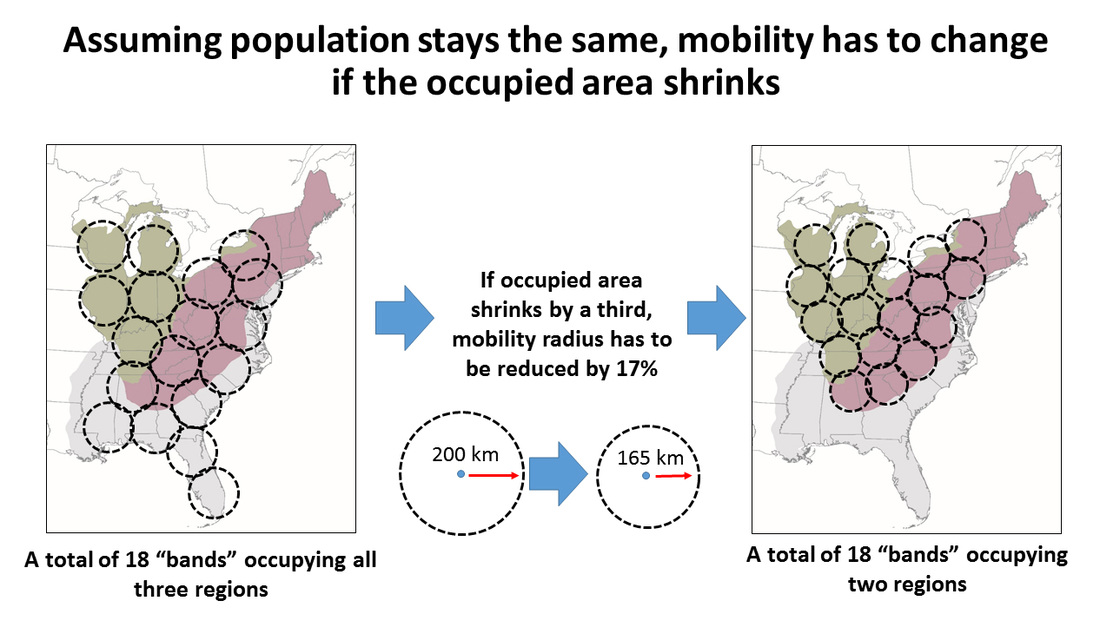

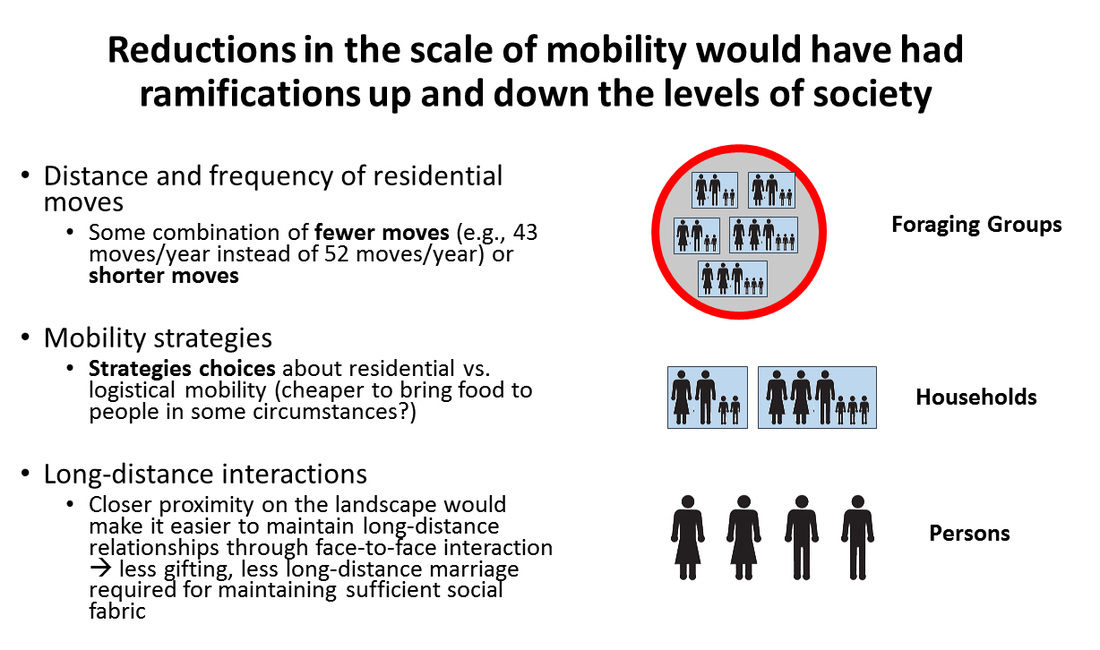

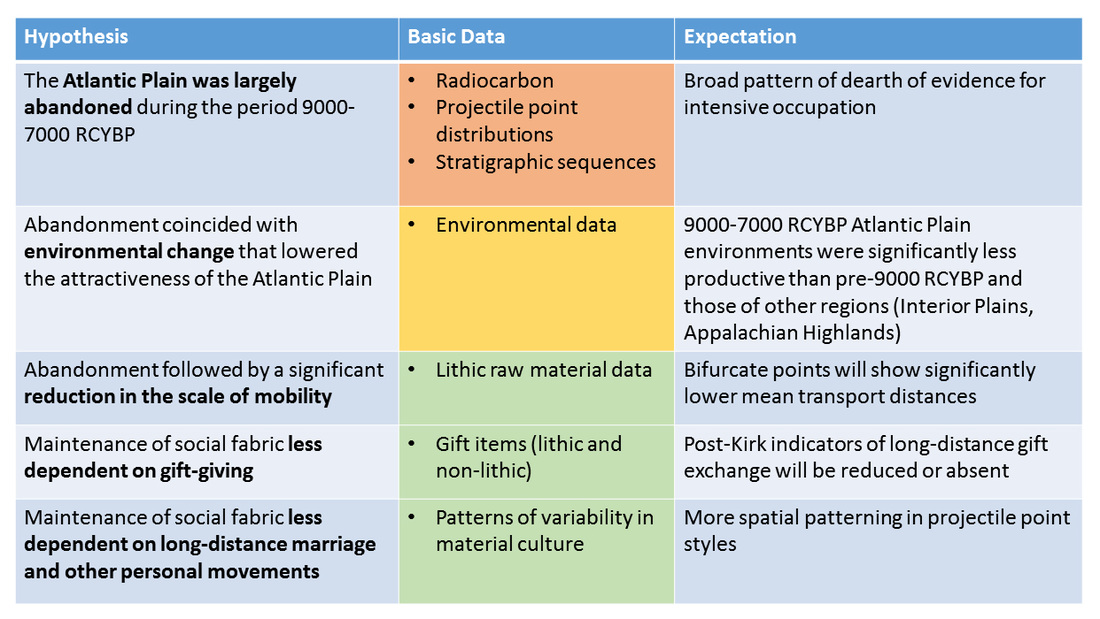

The session that really brought the point home was a symposim titled "A Ritual Gathering: Celeberating the Work of Cheryl Claassen" (Session 3 in the program). Claassen, a professor at Appalachian State, has been pushing the boundaries of the archaeological conversation in the Eastern Woodlands for decades (you can see some of her work on her Academia.edu page). The papers in this session (many by her students) evoked responses in me ranging from "what a profoundly interesting thought" to "are you sure about that?" to "get off my case." It was great. (As an aside, I wish that some of my friends on the "fringe" could have seen these papers. Perhaps if you witnessed a professional archaeologist discussing how the skeletal remains of immature bird wings in a feature were connected to the astronomical scheduling of seasonal ritual aggregation events, you'd have a better appreciation both for the kinds of questions that actual archaeology can address and the level of work it takes to convincingly address those questions. The claim that archaeologists are afraid to say anything new or different is preposterous.) I want to state clearly that, in my opinion, the expansion of thought that was on display in the Claassen session is a positive thing with a lot of potential upside. As an advocate of a complex systems approach to understanding human cultures in the past, it makes perfect sense to me that ritual and belief are involved in both "bottom up" and "top down" aspects of human societies. I see no logical or analytical reason to assume that ritual and belief are epiphenomenal or unimportant compared to other domains of social, economic, and political life. It all matters, and it's all fair game for trying to flesh out the past as best we can and trying to explain, using all the tools at our disposal, how those societies worked and why and how they changed. For me, however, my positive regard for the role of belief and ritual in human societies (and for the appropriateness of including it in our discussions) doesn't alleviate concerns about how we study it in the past tense. I know that I'm not alone here. I think several legitimate worries underlie uncertainties about both the approaches and the conclusions reached by those focused on belief and ritual. One concern that's out there -- perhaps the major one -- is a feeling that the "ritual" people are jumping outside the established lines of scientific process in a way that undermines confidence in their conclusions. Talking with a few of my colleagues about this, I got the sense that people are not closed to the questions so much as they are skeptical of the methods (or the perceived lack of methods) used to address those questions. I conceive of science as an inductive-deductive loop. On the inductive side, you create an explanation to fit a bunch of data. On the deductive side, you collect new information to test an expectation derived from your explanation. Ideally, the two sides of the loop are exploited together to create (eventually) a credible explanation that fits all the available information and makes further predictions about the world that are falsifiable but not falsified. As long as you get yourself into this loop, you're doing science. It doesn't really matter what the starting point is or where an idea comes from as long as you're willing to follow through and ride the inductive-deductive roller coaster around the track for as long as it takes. Are there ways to skeptically evaluate ideas about Archaic ritual and belief systems and make sure we're utilizing the full power of the inductive-deductive loop? I'm sure that there are. What I'm less sure of, at this point anyway, is the presence of an appetite for the deductive side of the loop that matches the robust enthusiasm for climbing up the inductive side. No matter how interesting or appealing an interpretation is, you still have to put on the skeptic glasses and try to find the seams you can follow to figure out whether you're right or wrong. The inductive-deductive loop is critical in archaeology because of all of our equifinality problems: there's usually more than one way something could have happened, so how do you know what the real cause was? You have to do the work to assemble independent lines of evidence, build theory, collect data, construct and test hypotheses, etc. You can't skip all that and just hug an assertion. Well, you can, but I won't buy what you're selling. That leads me to a second concern: the burden of proof. Who's is it? Does it have to reside in one domain of inquiry, or is it the responsibility of the person making the claim no matter what the claim actually is? At one point in the session I heard the phrase "can you prove it's not a ritual assemblage?" I take the point of the question (which was used mainly, I think, to argue that we should always consider ritual as a possibility), but I'm uncomfortable with the notion that we should accept/assume that something is related to ritual unless we can prove it's not. I think we all realize that people's lives are often not partitioned neatly into "ritual" and "non-ritual" components, but that doesn't mean all activities should be presumed to be ritualistic in nature unless we can prove they're not. That seems to me to be out of bounds of the way good science is done. There has to be a positive case made for a claim, whether it's about ritual or not. And that brings me to my third concern: the appeal to human "universals" to gird claims about past ritual behavior. Several times, in several different papers, I heard the assertion that all humans share a basic set of experiences in the material world and therefore all belief systems share a similar set of components tied to that material world: fire transforms, the sky is above and the earth is below, water goes down and smoke goes up, etc. This seems logical and may well be true (I haven't yet read through the arguments to evaluate them on my own). My concern is not that such universals don't exist, but that playing the "universal" card as the basis for analysis rather than an empirical problem may do two counter-productive things: (1) short circuit the inductive-deductive cycle by introducing a powerful, unvetted assumption; and (2) actually bland out the kind of contextual variability that could potentially be very interesting and analytically useful. This last point is somewhat ironic. Many of the issues that the pursuit of ritual and belief articulates with have a particularly "post-processual" flavor. One of the main critiques leveled at the processual archaeology of the late twentieth century was that it didn't account for the meanings of objects in their contexts. Symbols and objects do not mean the same things in different cultures: context matters. It seems to me that by falling back to "universals" as explanation we're actually ignoring context altogether -- if something is present everywhere, what meaning does it actually have? One of my professors at Southern Illinois University was fond of repeating the phrase "playing ethnosemantic tennis with the net down" (if my memory serves me right, he used the phrase in connection with criticisms of Claude Levi-Strauss). If we lay down a foundation of presumed "universals" and then build an analysis based on those, I worry that we're lowering the net significantly if not taking it down altogether. Opening things up is great for generating discussion and new approaches, but at some point the net has to go back up so we can have some mechanism for discriminating between credible and non-credible explanations. I'm excited by what I saw and heard at SEAC. We've still got a long way to go to address many basic space-time issues for some of the questions that I and many others are interested in. That doesn't mean, of course, that we can't think about other additional things while that's going on. I bought Claassen's (2015) book Beliefs and Rituals in Archaic Eastern North America at SEAC. I look forward to seeing what's inside and comparing it to my own views and knowledge about the eastern Archaic. Nothing that I've said in this post should be construed as pointing at the content of the book, which I have not read yet. I anticipate the book will be a stimulating read. Should be fun! Archaeological conferences serve several purposes. For me, there are three main attractions, all selfish: (1) meeting people; (2) learning about things I didn't know that I didn't know about; and (3) clarifying and catalyzing my own research. Conferences are fun, but they're also a bit mercenary -- I want something from them. This year's Southeastern Archaeological Conference (SEAC) is in Athens, Georgia, which I hear is very nice. I put together a small symposium titled "Hunter-Gatherer Societies of the Late Pleistocene and Early Holocene Southeast" (session 35 in the program). I originally wrote about the idea last April. We ended up with papers by seven presenters: Al Goodyear, Doug Sain, David Thulman and Maile Neel, Kara Bridgman Sweeney, Joe Wilkinson, Sarah Gilleland, and me. Here is the symposium abstract: "Societies are groups of people defined by persistent social interaction. While the characteristics of the late Pleistocene and early Holocene hunter-gatherer societies of the Southeast certainly varied, archaeological data generally suggest that these societies were often geographically extensive and structurally complex. Patterns of artifact variability and transport, for example, demonstrate that small-scale elements (e.g., individuals, families, and foraging groups) were situated within much larger social fabrics. This session aims to explore the size, structure, and characteristics of early Southeastern hunter-gatherer societies, asking how patterns of face-to-face interactions at human scales “map up” to and are affected by larger social spheres." I decided to use my contribution to think about the issue of a possible abandonment of the deep south during the later portion of the Early Archaic period. Here is the abstract for my presentation, titled "Social Implications of Large-Scale Demographic Change during the Early Archaic Period in the Southeast:" "Previous studies of radiocarbon and projectile point distribution data have suggested the possibility of a significant shift in the distribution and/or behaviors of human populations during the later portion of the Early Archaic period (i.e., post-9000 RCYBP). This paper considers the evidence for an “abandonment” of large portions of the Southeast following the Kirk Corner Notched Horizon and explores (1) possible explanations for large-scale changes in the distribution of population in the Early Holocene and (2) how those demographic changes, if they occurred, might have articulated with social changes at the level of the family, foraging group, and larger societies." I first became interested in the Early Archaic abandonment issue while reading Ken Sassaman's (2010) book Eastern Archaic, Historicized. Working on this presentation was fun because it forced me to try to think through some of the issues about how we would recognize a large-scale abandonment, what the abandonment process actually would have been like, and what the social ramifications might have been for the people and societies involved in that process. I'll tweak the presentation before I give it, but it's pretty close to done. The first question is to ask is whether or not there was a large-scale abandonment of parts of the Southeast. On the surface (at least), I think the case is fairly compelling. Following the example of Faught and Waggoner's (2012) paper about Florida, I started compiling radiocarbon data from across the Eastern Woodlands to evaluate the idea. At 9,500 dates and counting, the radiocarbon database that I'm working on clearly supports the idea that there are far fewer than expected dates from 9000-7000 radiocarbon years before present (RCYBP) in the deep south: A chi square easily defeats the null hypothesis: there just aren't as many radiocarbon dates from 9000-7000 RCYBP below the southern corner of South Carolina as you'd expect by chance. The pattern holds when you consider the number of dates during that period in the entire Atlantic Plain vs. the other major physiographic regions of the eastern United States (the Appalachian Highlands and the Interior Plains). The idea of a large-scale abandonment is also consistent with the distribution of post-Kirk lobed/bifurcate projectile points, which (unlike Kirk), does not extend into Louisiana, Florida, and southern Mississippi, Alabama, and Georgia. If we presume that a post-Kirk abandonment/marginalization of the Atlantic Plain did occur, we can move on to the "why" and "how" questions. Regarding the "why" question: the limited environmental data I've looked at (e.g., the 1980 pollen core from White Pond, South Carolina) suggest that the period 9000-7000 RCYBP was one of significant change. Oak and hickory decreased and pine increased. In simplest terms, this shift may have been related to a decrease in mast production, perhaps affecting the density of white-tailed deer (probably the primary game species for early Holocene hunter-gatherers in the Eastern Woodlands). But how would an abandonment actually take place? I can think of several ways that populations could shift out of an area. My gut is that an abandonment of the Atlantic Plain during the late Early Archaic would have most probably involved a contraction of populations into the Appalachian Highlands and Interior Plains. One of my favorite of Lew Binford's papers is his (1983) discussion of how hunter-gatherers often make extensive use of the landscape. Keeping his examples in mind, it's easy to imagine how "abandonment" could actually be the end result of a long-term process involving segments of the population getting "pulled in" to better quality environments in the course of normal decisions about movement. Assuming population size stayed constant, this shift would have necessarily involved changes in mobility. If (based on Midwestern data) we assume that Kirk "bands" had a group mobility radius of about 200 km, there would have been room for about 18 such "bands" in the Eastern Woodlands. If you took that same population and crammed them into an area 33% smaller (i.e., the Eastern Woodlands minus the Atlantic Plain), the scale of group mobility would have to be reduced by 17% (mobility radius of 165 km) to keep everything else the same. That level of population contraction would have almost certainly had ramifications up and down the levels of those post-Kirk societies. Residential moves would have decreased in frequency and/or distance, there may have been shifts in logistical vs. foraging strategies, and the lowered "cost" of maintaining extra-local inter-personal relationships may have de-emphasized gift exchange and inter-group marriage as mechanism for creating and maintaining distant social ties. It's possible to develop a suite of hypotheses and archaeological expectations to evaluate the idea of a large scale abandonment. Make no mistake: these are long-term propositions. My entire dissertation, for example, was focused on using a combination of modeling and archaeological data to try to understand how changes in patterns of variability in material culture were related to changes in the characteristics and properties of social networks. It's not trivia, and it's not easy.

For me, this presentation was a machine for thinking. I can't "prove" anything, but going through the process of committing to an idea and preparing a presentation has forced me to attempt to think through some complex, interesting issues. I'm hoping I'll get some good feedback on my ideas ("interesting" and/or "you're full of it"), which obviously involve an extensive geographic area that I make no claim to have mastered. I also hope to take full advantage of my hotel and at least quadruple my supply of ink pens. Every little bit helps.  We're now into the fourth week of the semester here at the University of South Carolina. As usual I've been writing for this blog less than I'd like (I have several unfinished draft posts and ideas for several more, and there's currently a backlog of Fake Hercules Swords). A good chunk of my time/energy is going into the Forbidden Archaeology class (you can follow along on the course website if you like -- I've been writing short synopses, and student-produced content will begin to appear a few weeks from now). Much of the remainder has gone into pushing forward the inter-locking components of my research agenda. This is a brief update about those pieces. Small-Scale Archaeological Data At the beginning of the summer I spent a little time in the field doing some preliminary excavation work at a site that contains (minimally) an intact Archaic component buried about 1.9 meters below the surface (see this quick summary). Based on the general pattern here in the Carolina Piedmont and a couple of projectile points recovered from the slump at the base of the profile, my guess is that buried cultural zone dates to the Middle Archaic period (i.e., about 8000-5000 years ago). My daughter washed some of the artifacts from the site over the summer, and I've now got an undergraduate student working on finishing up the washing before moving on to cataloging and labeling. Once the lithics are labeled we'll be able to spread everything out and start fitting the quartz chipping debris back together. Because I piece-plotted the large majority of the lithic debris, fitting it back together will help us understand how the deposit was created. I'm hoping we can get some good insights into the very small-scale behaviors that created the lithic deposit (i.e.,perhaps the excavated portion of the deposit was created by just one or two people over the course of less than an hour).  Drawing of the deposits exposed in profile. The numbers in the image are too small to read, but the (presumably) Middle Archaic zone is the second from the bottom if you look at the left edge of the drawing. Woodland/Mississippian pit features are also exposed in the profile nearer the current ground surface. When the archaeology faculty met to discuss the classes we'd be offering in the spring semester, I pitched the idea of running a one-day-per-week field school at the site. Assuming I can get sufficient enrollment numbers, that looks like it's going to happen. The site is within driving distance of Columbia, so we'll be commuting every Friday (leaving campus at 8:00 and returning by 4:00). The course will be listed as ANTH 322/722. It's sand, it's three dimensional, and it's pretty complicated -- it's going to be a fun excavation. I'll be looking to hire a graduate student to assist me on Fridays, and I'll be applying for grant monies to cover the costs of the field assistant's wages, transportation, and other costs associated with putting a crew in the field. Large-Scale Archaeological Data Some parts of my quest to assemble several different large-scale datasets are creeping along, some are moving forward nicely, and some are still on pause.

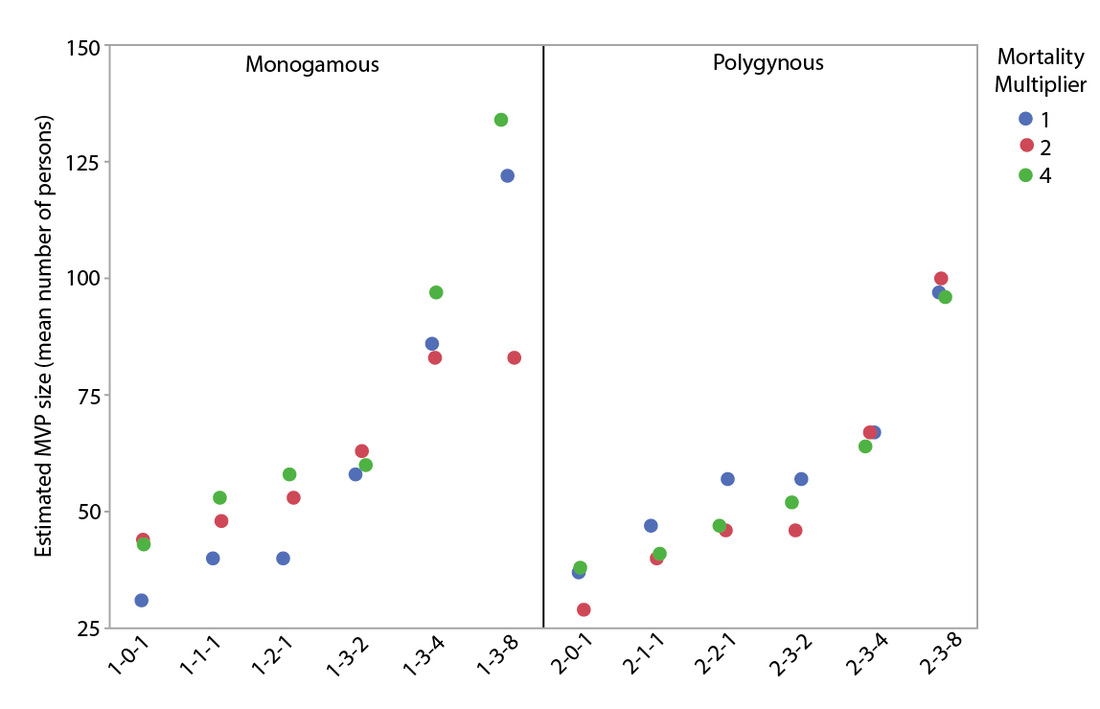

Complex Systems Theory and Computer Modeling Complex systems theory is what will make it possible to bridge the small and large scales of data that I'm collecting. Last year, I invested some effort into transferring my latest computer model (FN3_D_V3) into Repast Simphony and getting it working. I also started building a brand new, simpler model to look at equifinality issues associated with interpreting patterns of lithic transport (specifically to address the question of whether or not we can differentiate patterns of transport produced via group mobility, personal mobility between groups, and exchange). As it currently sits, the FN3_D_V3 model is mainly demographic, lacking a spatial component. Over the summer I used it to produce data relevant to understanding the minimum viable population (MVP) size of human groups. Those data, which I'm currently in the process of analyzing, suggest to me that the "magic number of 500" is probably much too large: I have yet to find evidence in my data that human populations limited to about 150 people are not demographically viable over spans of several hundred years even under constrained marriage rules. But I've just started the analysis, so we'll see. I submitted a paper on this topic years ago with a much cruder model and didn't have the stomach to attempt to use that model to address the reviewers' comments. I'm hoping to utilize much of the background and structure of that earlier paper and produce a new draft for submission quickly. I also plan to put the FN3_D_V3 code online here and at OpenABM.org once I get it cleaned up a bit. I also discuss this model in a paper in a new edited volume titled Uncertainty and Sensitivity Analysis in Archaeological Computational Modeling (edited by Marieka Brouwer Burg, Hans Peeters, and William Lovis).  How big does a human population have to be to remain demographically viable over a long span of time? Perhaps not as big as we think. The numbers along the bottom axis code for marriage rules (which will be explained in the paper). Generally, the rules get more strict from left to right within each category: 2-0-1 basically means there are no rules, while 2-3-8 means that you are prohibited from marrying people within a certain genetic distance and are compelled to choose marriage partners from within certain "divisions" of the population. It will be a relatively simple thing to use the FN3_D_V3 model in its non-spatial configuration to produce new data relevant to the Middle Paleolithic mortality issue I discussed at the SAA meetings a couple of years ago. I'm also going to be working toward putting the guts of the demographic model into a spatial context. That's going to take some time.

Current and Not-So-Current Events: Excavation, Moving, and Other Early Summer Odds and Ends5/27/2016  My new home. My new home. It's been two weeks since my last blog post. I've spent much of that two weeks away from my computer, which has been a nice change. Since the semester ended, I've been working in the field, doing stuff around the house and with my family, and prepping my office for a move. Today I'm relocating from the main SCIAA building to a larger, nicer office suite right in the heart of campus. I'll have plenty of room to ramp up my research, process and analyze artifacts, store collections I'm working on, and (hopefully) start getting some student work going. It's really an amazing thing to have the space -- it's larger and nicer than many fully functional archaeology labs where I've worked in the past. A 6000-Year-Old Moment Frozen in Time? Archaeological sites are places that contain material traces of human behavior. While the human behaviors that create archaeological sites are ultimately those of individuals, we usually can't resolve what we're looking at to that level. Traces of individual behaviors overprint one another and blend into a collective pattern. The granularity of individual behavior is usually lost. Usually, but not always. I spent portions of the last couple of works doing some preliminary excavation work at a site I first wrote about last October. Skipping over the details for now, documentation of an exposed profile measuring about 2.2 meters deep and 10 meters long showed the presence of cultural materials and intact features at several different depths. The portion of the deposits I am most interested in is what appears to be a buried zone of dark sediment, fire-cracked rock, and quartz knapping debris about 1.9 meters below the present ground surface. Based on the general pattern here in the Carolina Piedmont and a couple of projectile points recovered from the slump at the base of the profile, I'm guessing that buried cultural zone dates to the Middle Archaic period (i.e., about 8000-5000 years ago).  A buried assemblage of quartz chipping debris, probably created by a single individual during a single knapping episode. A buried assemblage of quartz chipping debris, probably created by a single individual during a single knapping episode. I did quite a bit of thinking to come up with my plan to both stabilize/preserve the exposed profile and learn something about the deposits. After I cleaned and documented the machine-cut profile as it existed, I established a coordinate system and began systematically excavating a pair of 1x1 m units that cut into the sloping face of the profile above the deposit of knapping debris visible in the wall. Excavating those partial units allowed me to simultaneously plumb the wall and expose the deposit of knapping debris in plan view. While there is no way to know for sure yet, I think I exposed most of the deposit, which seemed to be a scatter of debris with a concentration of large fragments in a space less than 60 cm across (an unknown amount of the deposit was removed during the original machine excavation, and I recovered numerous pieces of quartz debris from the slump beneath the deposit). My best guess is that pile of debris probably marks where a single individual sat for a few minutes and worked on creating tools from several locally-available lumps of quartz. I piece-plotted hundreds of artifacts as I excavated the deposit, so I'll be able to understand more about how it was created when I piece everything back together.  I did what I came to do. I did what I came to do. The site I've been working on would be a great one for a field school. It is close to Columbia and has all kinds of interesting archaeology -- great potential for both research and teaching. This May I was out there by myself. It took just about every move of fieldwork jiu jitsu I know (and several that I had to invent on the spot) to do what I did to stabilize the site and get it prepped for a more concerted effort, but I think it's in good shape now. Once I get moved into my new lab space I'll be able to start processing the artifacts and doing a preliminary analysis. I'll keep you posted. The Anthropology of Prehistoric Hunter-Gatherers in the Eastern Woodlands? Earlier in the month, I had the privilege of visiting the archaeological field schools being conducted at Topper. I wrote a little bit about the claim for a very early human presence at Topper here. The excavations associated with that claim aren't currently active. Field schools focused on Late Pleistocene/Early Holocene (Mississippi State University and the University of West Georgia) and Woodland/Mississippian (University of Tennessee) components at Topper and nearby sites have been running since early May. Seeing three concurrent field schools being run with the cooperation of personnel from four universities (and many volunteers) is remarkable.  On the day of my visit, I gave a talk titled "The Anthropology of Prehistoric Hunter-Gatherers in the Eastern Woodlands?" I argued that not only is it possible to do the anthropology of prehistoric peoples, but it should be a fundamental goal. Skipping over the details for now, I argued (as I have elsewhere) that complex systems science provides a set of tools for systematically trying to understand how history, process, and environment combine to produce the long-term, large-scale trajectories of prehistoric change that we can observe and analyze using archaeological data. I talked about each of the components of my three-headed monster research agenda. And I got to eat various venison products prepared under the direction of my SCIAA colleague Al Goodyear. And I got to see alligators swimming in the Savannah River. As a native Midwesterner . . . I anticipate that working near alligators will remain outside my comfort zone for some time to come. When Did Humans First Move Out of Africa? Archaeologists love finding the earliest of anything and people love reading about it. While we often want to know how/when new things appear, identifying the "earliest of X" often gets play in the popular press that is disproportionate to its relevance to a substantive archaeological/anthropological question. And you can never really be sure, of course, that you've nailed down the earliest of anything: someone else could always find something earlier, falsifying whatever model was constructed to account for the existing information and moving the goal posts. Exactly a year ago, I wrote about the reported discovery of 3.3 million-year-old stone tools from a site in Kenya. Those tools are significantly earlier than the previous "earliest" Oldowan tools. I think they're really interesting but not particularly surprising: several other lines of evidence (cut marks on bone, tool-use among chimpanzees, and hominin hand anatomy) already suggested that our ancestors were using tools well before the earliest Oldowan technologies appeared. I anticipate that we still haven't seen the "earliest" stone tool use. A recent report from India argues that our ideas about the "earliest" humans outside of Africa also miss the mark. (Note: when I say "human" I'm referring not to "modern human" but to a member of the genus Homo.) This story from March discusses a report of stone tools and cutmarked bone from India purportedly dating to 2.6 million-years-ago (MYA), blowing away the current earliest accepted evidence of humans outside of Africa (Dmanisi at 1.8 MYA) by about 800,000 years. With an increasing number of Oldowan assemblages dating to about 1.8-1.6 MYA are being reported outside of Africa (e.g., in China and Pakistan), would it be that surprising to find evidence a migration pre-dating 1.8 MYA? Probably not. Do the finds reported from India cement the case for human populations in South Asia at 2.6 MYA? Not yet: the fossils and tools reported from India so far (as far as I know anyway) don't have a context that allows them to be convincingly dated. My Conversation with Scott Wolter  Forbidden Archaeology (ANTH 291-002): It's going to worthwhile. Forbidden Archaeology (ANTH 291-002): It's going to worthwhile. I had a pleasant conversation with Scott Wolter yesterday. I emailed him to touch base about his participation in my class in the fall, and we ended up talking for about 45 minutes. It was the first time we've spoken and we had more to talk about than we had time to talk. We talked about the Wolter-Pulitzer partnership, of course, but I'm not going to go into the details of our discussion (I just invite you to read for yourself Pulitzer's bizarre word salad blog post from Wednesday containing his reference to me as "some back woods rural South Carolina Pseudo-Archaeologist who never worked in the field, but only learned from books"). My sense is that Wolter is someone with whom I can have a frank and vigorous discussion about the merits and interpretation of archaeological evidence and how it is used to evaluate ideas about the past. I'm looking forward to his participation in my class. My plan is to start a Go Fund Me campaign to raise money to fly him down here so he can interact with the students on a face-to-face basis. And now the movers are coming for my filing cabinets. And now my chair is gone. And now you are up-to-date.

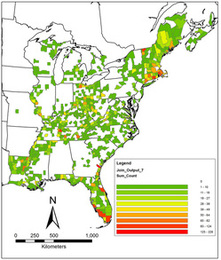

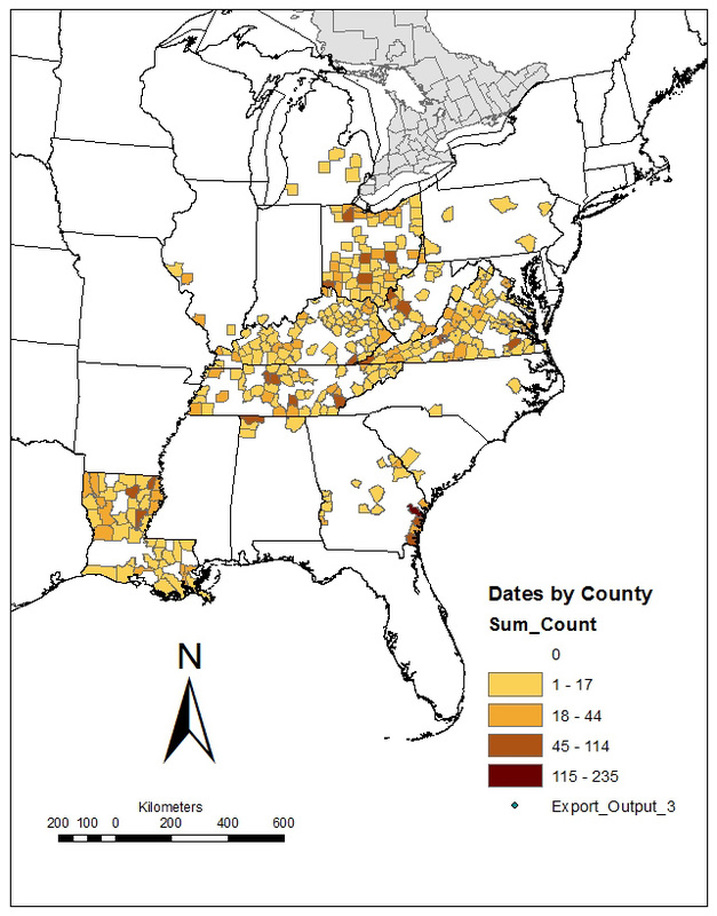

I've been working on compiling a database of radiocarbon dates from the Eastern Woodlands. While my interest in doing this is mainly driven by my own research goals (the driving force right now is my desire to be able to discuss the possible abandonment of portions of the Southeast at the end of the Early Archaic period in a symposium I'm pulling together for the 2016 SEAC meetings this fall), I know these data will be useful to others as well. Here is a GIS map showing the counts by county of the first 4,870 dates that I've gotten plugged in: I started with a spreadsheet sent to me by Shane Miller and combined it with data available online from PIDBA (both of those sources were focused on dates from early sites across the east), the Louisiana Division of Archaeology, the Virginia Department of Historic Resources, the Kentucky, Ohio and West Virginia Radiocarbon Database (Cultural Resource Analysts, Inc.), a list of Tennessee radiocarbon dates (Tennessee Archaeology Network), and A Comprehensive Radiocarbon Date Database from Archaeological Contexts on the Coastal Plain of Georgia by John A. Turck, and Victor Thompson. After combining these datasets into a single database (which took some effort), I did a sweep to eliminate redundancies and flag obvious errors. I added a column for county and linked that to a separate table of county names attached to UTM coordinates of the approximate center of the county. That lets me query the database to spit out a table containing a listing of dates and associated UTMs. I imported that into GIS and then did a "join" to count the number of points per county. Voila.

There are still numerous errors and omissions in the database as it currently stands, which is why I'm not prepared to supply the raw data at this point. I've got many dates that are missing key pieces of information (error, site number, county, etc.), and the columns for references are a total mess at this point. As I work through the process of cleaning all that up and trying to fill in blanks, I'll be adding new data. I know of some print publications that will help me fill in some of the large blank areas, and I suspect there are other online or electronic sources of data out there. I've got the UTM coordinates for the counties in most of the Midwest and Southeast (I still haven't done Mississippi and Florida), but I haven't yet started on the tier of states immediately west of the Mississippi River (Arkansas, Missouri, Iowa, and Minnesota) or the Northeast and New England.  I Googled "hunter-gatherer Athens Georgia" and I found this picture of the drummer of a band called "Hunter Gatherer" playing in Athens, GA. That's good enough for a blog post about a symposium abstract. I Googled "hunter-gatherer Athens Georgia" and I found this picture of the drummer of a band called "Hunter Gatherer" playing in Athens, GA. That's good enough for a blog post about a symposium abstract. The annual meeting of the Society for American Archaeology (SAA) is in Orlando, Florida, this week, running from Wednesday through Sunday. I'm not giving a paper this time around (though I did just sign up to do a 3 minute lighting talk in the Digital Data Interest Group), but I'm looking forward to driving down and hearing about what others have been up to lately. I'm also going to be asking around (and maybe, although I've never been very good at it, attempting to twist a few arms) to try to lock in some participants for a symposium I'm working on for the 2016 Southeastern Archaeology Conference (SEAC) meeting that will be held in Athens, Georgia, in October. Here is the draft of an abstract I wrote this morning: Hunter-Gatherer Societies of the Early Holocene Southeast Societies are groups of people defined by persistent social interaction. While the characteristics of the early Holocene (> 5000 RCYBP) hunter-gatherer societies of the American Southeast undoubtedly varied across time and space, archaeological data generally suggest that they were often geographically extensive. Patterns of artifact variability and transport, for example, demonstrate that small-scale elements (e.g., individuals, families, and foraging groups) of these Early and Middle Archaic societies were situated within much larger social fabrics. The goal of this session is to explore the size, structure, and characteristics of these early Holocene hunter-gatherer societies, asking how patterns of face-to-face interactions at human scales “map up” to and are affected by larger social spheres. Theoretical and methodological diversity are welcome, as is an interest in integrating various scales of archaeological data analysis. I'm hoping this will appeal to a range of scholars, especially those who like to work on multiple scales and address difficult questions. Ideally, we can get a group of papers together that will be suitable for an edited volume. The first job, however, is seeing what kind of interest there is and who I can get commitments from. Everything will have to be decided and submitted by the end of August. If you read this and you're interested, please let me know: aawhite@mailbox.sc.edu.

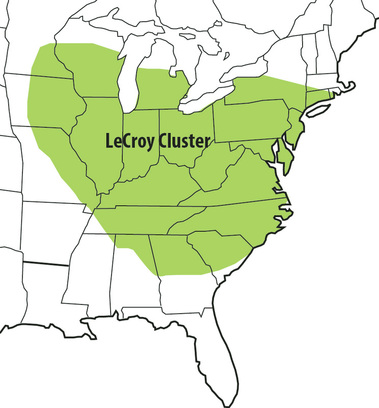

I've got several ideas for what I'll contribute to the session. Something related to Kirk is an obvious one, but I've also been spending more time thinking about the Early/Middle Archaic transition after reading Ken Sassaman's book. I'm wondering if we can: (1) use multiple lines of evidence to identify an abandonment of the Southeast during the late Early Archaic; (2) generate some explanations for that abandonment; (3) understand how social structure would have affected (and been affected by) whatever the causes of an abandonment were and whatever processes were in operation. And I'm also in the last stages of writing a new agent-based model that I'm going to use to try to attack the equifinality problem that hampers our ability to differentiate among group mobility, personal mobility, and exchange as mechanisms for the very-long-distance transport of stone artifacts. As I mentioned briefly in a post yesterday, I've become interested in looking into the evidence for an abandonment of large portions of the Southeast at the end of the Early Archaic period. This (2012) paper by Michael Faught and James Waggoner provides an example of how this could be done on a state-by-state basis. Faught and Waggoner use multiple lines of evidence to evaluate the idea of a population discontinuity between the Early Archaic and Middle Archaic periods in Florida. One of the things they discuss is the presence of a radiocarbon data gap between about 9000 and 8000 radiocarbon years before present (RCYBP). They are able to identify that gap (which is consistent with a significant drop in or lack of population at the end of the Early Archaic using a dataset of 221 pre-5000 RCYBP radiocarbon dates from Florida.  Geographical distribution of LeCroy cluster points (roughly following Justice 1987). Geographical distribution of LeCroy cluster points (roughly following Justice 1987). Assembly of radiocarbon datasets for states across the Eastern Woodlands would be really useful for seeing if there is a similar "gap" in other areas of the Southeast that correlates with technological and statigraphic discontinuities. It seems to me that small bifurcate points (e.g., LeCroy cluster) and/or larger lobed points (e.g., Rice Lobed cluster) are good candidates for marking a contraction or retreat of late Early Archaic hunter-gatherer populations. While common in the Midwest, such points are absent (?) from Florida and present in only parts of South Carolina, Georgia, Alabama. I'm aware of the Kentucky, Ohio, West Virginia Radiocarbon Database published by Cultural Resource Analysts, Inc. I'm wondering if there are similar existing compilations (either print or electronic) for other eastern states, especially those south of the Ohio River. I've only spent a short amount of looking, but I haven't come across any yet. At the risk of being accused of being lazy, I thought I'd throw the question out there and see what turns up. I will be very surprised if radiocarbon compilations haven't been produced for many areas of the east, and it seems worthwhile to ask about existing resources (which may not yet be easily "discoverable" online) before I contemplate yet another large-scale data mining effort. Please let me know if you can help. Update (3/27/2016): I've created this "Eastern Woodlands Radiocarbon Compilation" page to store links and references to radiocarbon compilations.

|

All views expressed in my blog posts are my own. The views of those that comment are their own. That's how it works.

I reserve the right to take down comments that I deem to be defamatory or harassing. Andy White

Email me: andy.white.zpm@gmail.com Sick of the woo? Want to help keep honest and open dialogue about pseudo-archaeology on the internet? Please consider contributing to Woo War Two.

Follow updates on posts related to giants on the Modern Mythology of Giants page on Facebook.

Archives

January 2024

Categories

All

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed