It was a lot of fun talking with Sara and Ken, and I hope I can do it again some day. Given the current resurgent interest in giants and all the different dimensions (historical, political, scientific, cultural, religions, etc.) of that interest, I don't think the topic is going away anytime soon. There will always be more to talk about: right now I've got more to write about than I've got time to write.

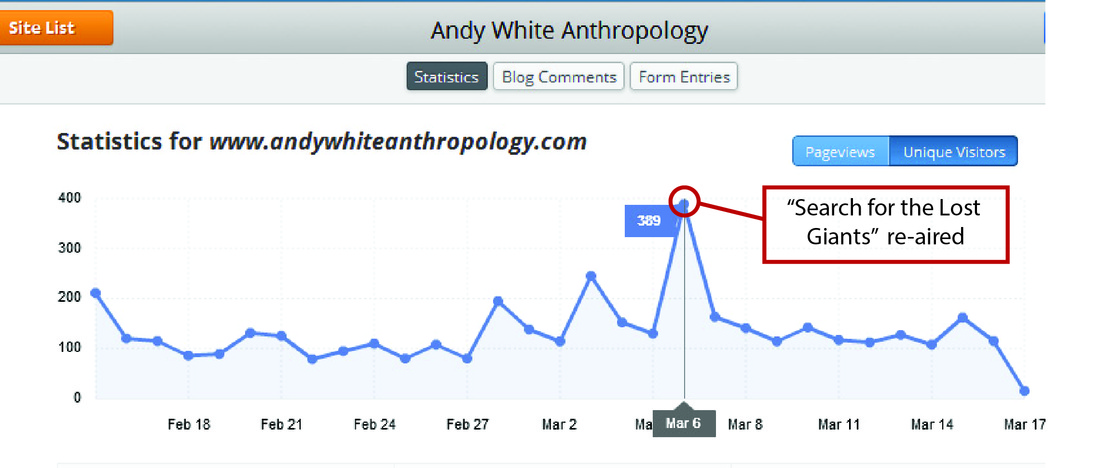

This was my first time being interviewed about this kind of subject in this kind of format. I'm sure I made some mistakes, and I'm sure I'll be told what they are. (And I'm sure I'm not the only one who finds it hard to listen to himself talk!) Sara introduces me as a "not giant expert" because, before the show began, I told them that it was hard to be comfortable being called an expert in something that doesn't actually exist. I just wrote a post this morning about some signs that my work on "giants" is having an impact. Shows like Sara and Ken's contribute to the goal of providing counter-points to many of the nonsense claims that are being manufactured and tossed around out there, and I'm glad they invited me on.

RSS Feed

RSS Feed